Truth, Trust, and the Case for Viewpoint Diversity

Misplaced arguments against intellectual pluralism

Mark Horowitz, PhD is an associate professor of sociology at Seton Hall University. He teaches and carries out research in the areas of sociological theory, political psychology, social movements, and the sociology of knowledge. He as published, among many other things, the following:

Anthropology’s Science Wars: Insights from a New Survey

You can also find him at these podcasts:

By Mark Horowitz and Lee Jussim

Lisa Siraganian’s essay, “Seven Theses Against Viewpoint Diversity,” published in AAUP’s flagship magazine, Academe, argues that calls for greater viewpoint/ideological/political diversity in academia are an engine for a pernicious and dysfunctional rightwing infiltration. It has also sparked widespread online criticism. These criticisms have much to recommend, but they fall short of driving home the flaws in her reasoning.

Indeed, Siraganian’s essay threw down the following gauntlet:

[Those] committed to “intellectual diversity,” have an obligation to refute—openly, fearlessly, and logically—the seven theses articulated above.

Though no one ever has an “obligation” to address any controversy, including this one, we accept her challenge. In this essay, we robustly defend the principle of viewpoint diversity and encourage readers to reject Siraganian’s caricature of arguments for viewpoint diversity in general, and Heterodox Academy (HxA) in particular, as trojan horses for reactionary politics.1

Rather than addressing each of Siraganian’s seven theses individually, we focus on what we take to be her four central claims. Only the first of these is arguably even partially defensible. The other three are not only mistaken but detrimental to scientific truth and efforts to restore public trust in higher education.

Siraganian’s four key arguments:

1) Conservative activists, such as David Horowitz, have long touted “intellectual diversity” as part of a larger ideological attack on higher education. The Trump administration has now seized the banner, deploying the concept in an authoritarian manner that threatens university autonomy.

2) As a “conservative nonprofit,” Heterodox Academy advances this political movement, and hence is not principally motivated to enhance universities’ pursuit of truth. When advocates call for viewpoint diversity, they do so in “bad faith,” as their real aim is to increase the number of conservatives in higher ed.

3) The call for viewpoint diversity is a call for viewpoint relativism, i.e., encouraging more diverse views is tantamount to welcoming all possible views, past or present, regardless of their empirical defensibility.

4) There is no evidence that increasing ideological diversity will enhance the pursuit of truth, which is best safeguarded “locally” at the program level. Indeed, the aims of viewpoint diversity and truth “directly conflict.”

We now consider each in turn.

1. “Viewpoint Diversity is a MAGA Plot.”

No, really, that is not us strawmanning her argument, that is in her own words.

Even though this sort of analysis is 99% leftwing academic conspiracist ideation dressed up as a critique of viewpoint diversity, she is not completely wrong. That the ideological “blueprint” of Trump’s attack on higher education echoes David Horowitz’s 2002 “Academic Bill of Rights” – is accurate enough. But putting Horowitz on some sort of pernicious pedestal as the founder of the emphasis on viewpoint diversity to advance rightwing agendas is absurd. Calls for viewpoint diversity long predate Horowitz’s conservative movement and precious few of those stem from his efforts.

Such arguments are implicit in ancient philosophy (Socrates imploring us to question everything) and explicit in Mill’s classic, On Liberty.2 Hence, the idea that today’s calls for viewpoint diversity trace exclusively, or even primarily, to Horowitz is worse than unjustified; we are not sure whether it is more ignorant than confused or more confused than ignorant, although maybe the idea stems mostly from hostility to Trump.

We will not relitigate whether Trump’s policies towards academia are best seen as authoritarian bullying or overdue accountability (or both). But the value of viewpoint diversity stands on its merits as a vital academic principle independent of anything Trump does. Siraganian either errs when she conflates the message with the messenger or, perhaps, purposely attacks the messenger because her main goal is to reveal the many evils of Trump, and not to actually improve science.

For example, the Supreme Court, in its 1978 Bakke decision – a decision that predates Horowitz by a generation – justified the use of race3 in admissions primarily on viewpoint diversity grounds. Here are some quotes from that decision (emphases added):

Our Nation is deeply committed to safeguarding academic freedom, which is of transcendent value to all of us, and not merely to the teachers concerned. That freedom is therefore a special concern of the First Amendment. . . . The Nation’s future depends upon leaders trained through wide exposure to that robust exchange of ideas which discovers truth “out of a multitude of tongues, [rather] than through any kind of authoritative selection.” United States v. Associated Press, 52 F.Supp. 362, 372.

The atmosphere of “speculation, experiment and creation” so essential to the quality of higher education is widely believed to be promoted by a diverse student body. As the Court [p313] noted in Keyishian, it is not too much to say that the “nation’s future depends upon leaders trained through wide exposure” to the ideas and mores of students as diverse as this Nation of many peoples.

Thus, in arguing that its universities must be accorded the right to select those students who will contribute the most to the “robust exchange of ideas,” petitioner invokes a countervailing constitutional interest, that of the First Amendment. In this light, petitioner must be viewed as seeking to achieve a goal that is of paramount importance in the fulfillment of its mission.

What the Court permitted, and what progressives and many academics like Siraganian seem to have conveniently forgotten, is that admissions that considered race were permitted, not for “social justice” reasons (which the Court explicitly rejected4), but for viewpoint diversity reasons. Indeed, we will never know whether academia could have avoided the 2023 Students for Fair Admissions decision (which rendered further use of race in admissions illegal) and the Trumpian anti-academia backlash, had it actually instituted what was legalized. Had academia prioritized viewpoint diversity in admissions (and hiring), which would have meant using many applicant characteristics for admissions, including but not restricted to race or other “oppressed group” memberships, it is possible that academia would not be in the mess it’s currently in and that the use of diversity in admissions would never have been overruled.

2. “Heterodox Academy (HxA) is a “conservative” nonprofit advancing a covert right-wing agenda; When advocates call for viewpoint diversity, they do so in “bad faith,” as their real aim is to increase the number of conservatives in higher ed.”

Heterodox Academy is demonstrably NOT a “conservative” nonprofit

Siraganian’s silly claim that HxA is a “conservative” organization collapses under the slightest scrutiny. Internal polling of Heterodox Academy members found more self-identified progressives (17%) than conservatives (14%). HxA Advisory Council members Cornel West and Irshad Manji would be surprised to hear they’re doing Horowitz’s or Trump’s bidding.

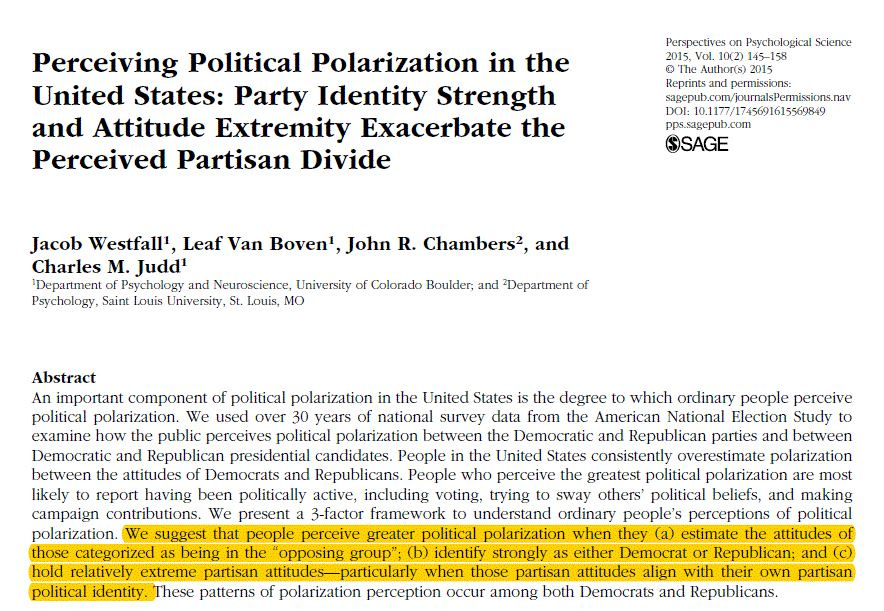

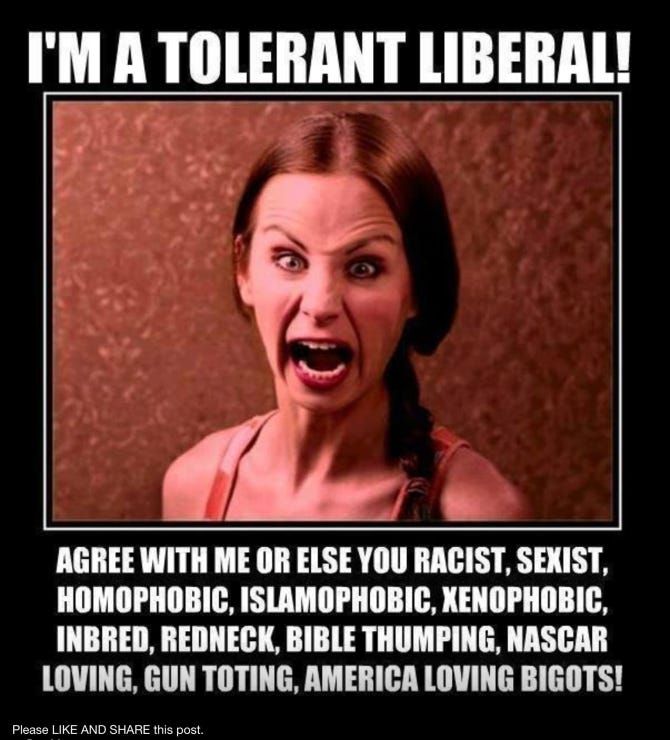

One of the marks of a true partisan, especially an extreme one, is exaggerating the positions of their opponents, as was amply demonstrated here:

Put differently, center left Democrats seem like Communists to a rightwing ideologue and center right Republicans seem like fascists to a leftwing ideologue.5 So when people (including but not restricted to Siraganian) view people and organizations like HxA as “conservative,” they are most likely revealing themselves to be leftwing ideologues whose ideology has distorted their political judgment. Or we could just do this as a meme:

“When advocates call for viewpoint diversity, they do so in “bad faith,” as their real aim is to increase the number of conservatives in higher ed.”

This Sirganian claim attempts to poison the well by attempting to render an argument she merely disagrees with as “bad faith.” For the reasons described throughout this essay, we both believe that increasing the number of non-leftists in the academy, and especially in the social sciences and humanities, would improve both scholarship and education on political and politicized issues. This includes but is not restricted to conservatives.

This is not a “bad faith” argument — it is central to the argument and we and others make it forthrightly on several grounds.

Academia is Massively Left Skewed

Contrary to mountains of evidence, Siraganian cherry picks an essay that downplays the prevalence of liberals in universities (this sort of cherrypicking is a clear marker of propaganda masquerading as scholarship). Yet even the report by the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) cited in the essay shows around a 5:1 ratio of liberal to conservative faculty.

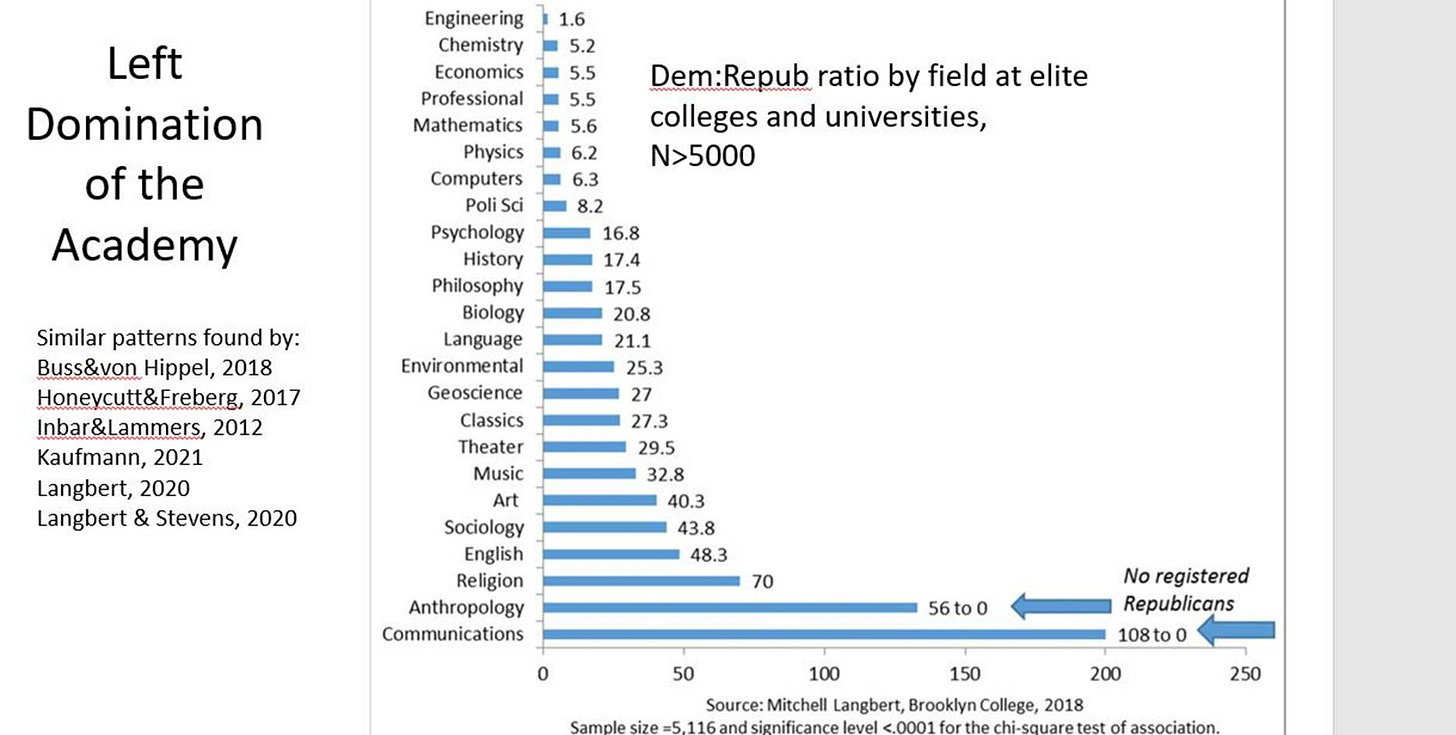

HERI data, however, has some odd characteristics. Thirty percent of the institutions it surveys are religious – and no one doubts that religious institutions skew more conservative than the rest of academia. It also does not focus on the prestigious and elite colleges and universities that are at the vanguard of sociocultural and political influences on the wider society. Research conducted at such places paints a far more extreme picture. For example, Langbert (2018) found a vastly more extreme skew in elite liberal arts colleges:

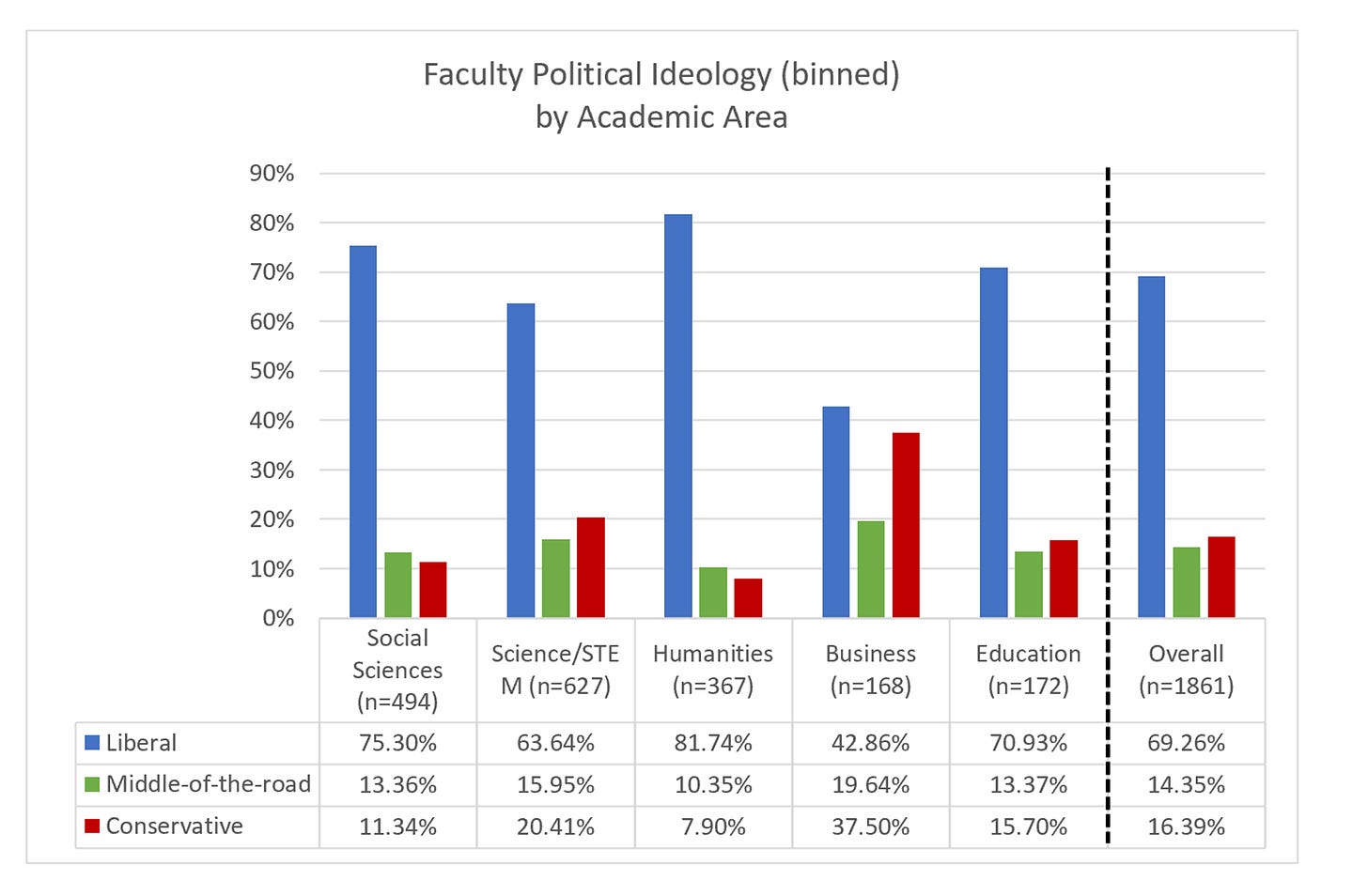

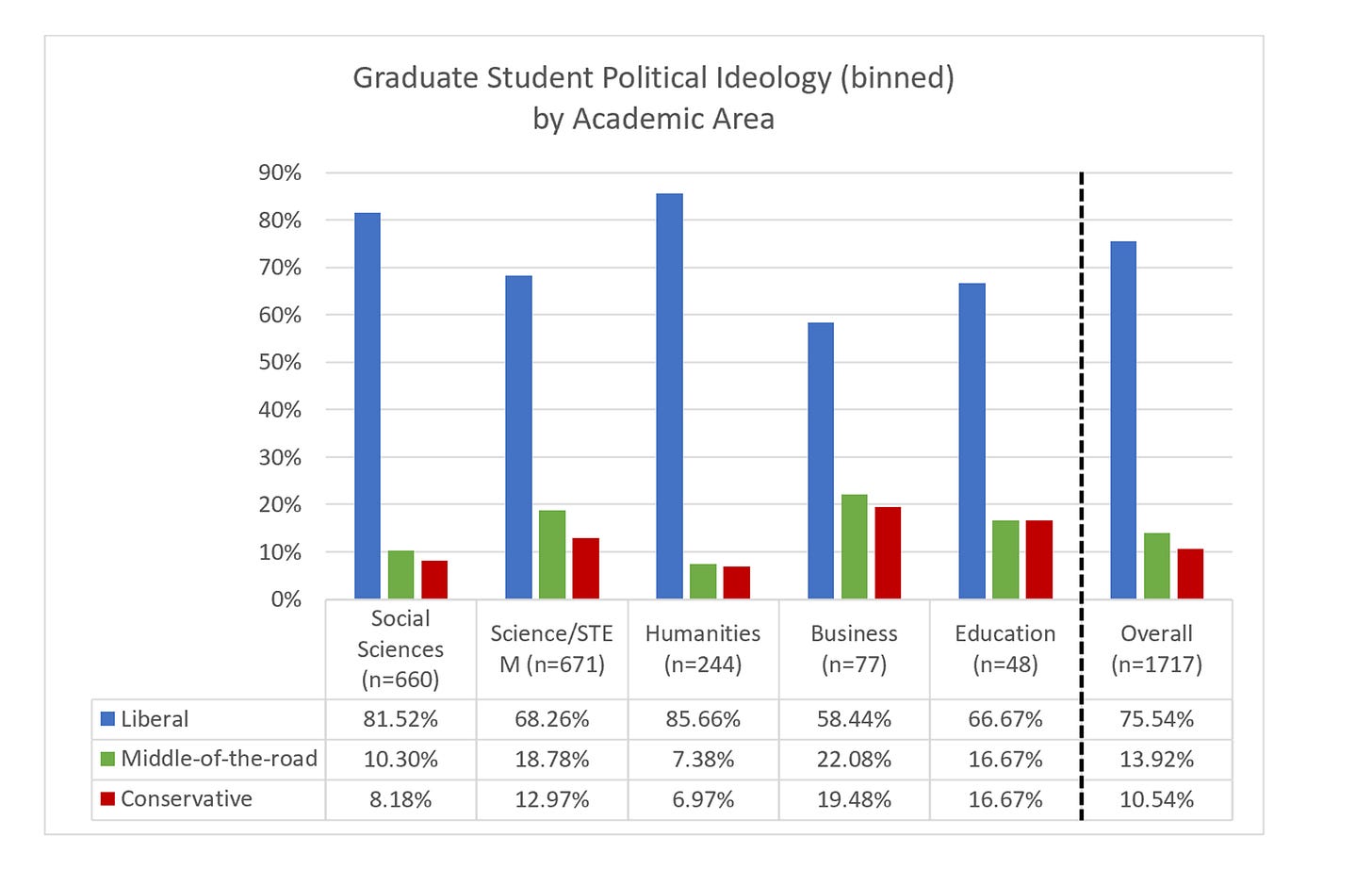

Honeycutt (2022, as yet unpublished doctoral dissertation, but which is currently submitted for publication) found comparable skews in his survey of faculty and graduate students at top (R1, R2) research universities:

Moreover, there are extreme imbalances in the social sciences. Horowitz and colleagues’ recent surveys document liberal-to-conservative ratios exceeding 20-to-1 among sociologists and 40-to-1 among anthropologists. Inbar and Lammers report a ratio of 14-to-1 among social psychologists. Even in economics, there are over twice as many self-identified liberals as there are conservatives and libertarians combined. Siraganian’s reliance on HERI data is therefore not only misleading but also selective: it downplays these far more pronounced disciplinary skews, which are especially acute at elite, influential institutions that shape public discourse on politics and society. By overlooking this evidence, she disregards the most dramatic manifestations of imbalance in precisely the fields where viewpoint diversity matters most for rigorous scholarship.6

Settled vs. Unsettled Science: No One is Calling for Geography Departments to Hire Flat Earthers

Siraganian dismisses concern over ideological monoculture on both conceptual and evidentiary grounds. Her conceptual argument is surprisingly callow. She writes that “the logic of viewpoint diversity contains its own extinction,” as any call for diversity of opinion obliges us to welcome all views – antiquated or absurd – into the conversation. Biology departments, Siraganian warns, would be compelled to rehash false theories of DNA’s triple helix. Chemistry programs would have to teach the phlogiston theory of combustion, and so on. She even quotes Chairman Mao (“Let one hundred flowers bloom”) to mock HxA president John Tomasi’s metaphor of an ideal university as a garden of diverse ideas. Heaven forbid we are encouraged to grow more than peas and carrots. We’ll have, according to Siraganain, no choice but to cultivate hemlock and poison oak!

This is a remarkably silly straw argument. Of course, no one advocates such intellectual relativism. No serious advocate of viewpoint diversity demands equal time for discredited theories.

So where, exactly, do we draw the line? Under what conditions should diverse ideas be considered important to consider versus excluded from serious scientific consideration? In our view, the principle here is straightforward. Viewpoint diversity is necessary for unsettled (social) scientific questions; it is not appropriate or necessary for settled scientific questions. We do not need viewpoint diversity regarding the speed of light, the heliocentric solar system, or the phlogiston theory of air. However, as far as we know, no scientists are clamoring to readjudicate these matters.

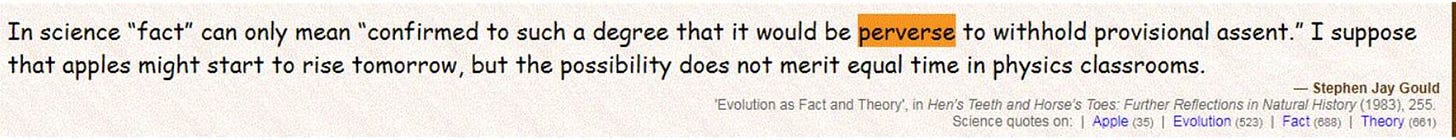

How can one know if some scientific claim is settled? Here we draw on the late evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould’s definition of scientific fact:

Science is settled when there is such a mountain of evidence supporting some claim that it would be perverse to disbelieve it. One of us (Jussim) has not too long ago added this corollary to Gould’s definition of scientific fact:

Science is not settled when the information available does not render someone perverse for holding doubts about the validity of some claim. Most claims in the social science literature fall into this latter category. They may or may not be true, but one is not being perverse for doubting them because only rarely do the social sciences provide the overwhelming mountain of indisputable evidence that justifies considering refusal to believe the claim as perverse.

Because this essay is not the place to provide a thorough review of highly popular yet ultimately debunked social science theories and claims, we will mention only a few:

Measures of “implicit bias,” once touted as measuring “unconscious racism,” are not unconscious, do not strongly correlate with discrimination, and changing scores on the most common measure of “implicit bias” had no effect whatsoever on discrimination (go here for a repository of about 50 sources documenting the criticisms, falsification, and contestations to major claims about implicit bias).

Research on ostensible microaggressions and their impacts assesses neither microaggressions nor their impacts.

Even though most psychologists surveyed claimed that experimental studies of sex bias in hiring would find evidence of substantial biases against women, since 2009, there is more evidence of biases against men than against women.

We could go on. Once popular social science claims and theories such as stereotype threat, multiple intelligences, stereotype inaccuracy, and the supposed nonexistence of reverse racism have all been debunked or at least hotly contested. It is precisely in such situations that embracing viewpoint diversity, despite its imperfections, is vastly superior to unjustifiably foreclosing on some trendy conclusion because it flatters the political biases of an academic monoculture.

The Value of Viewpoint Diversity for Resolving Political/Politicized Controversies in Unsettled Scientific Areas

Actual scientific research, especially at the frontiers of knowledge, occurs in areas where the answers are not yet known and the science is far from settled. Indeed, the primary purpose of original research is to attempt to address empirical questions in areas where the answers are not yet known. In these unsettled domains – common in social sciences, psychology, and some emerging natural sciences – viewpoint diversity is invaluable. It generates the essential clash of ideas that allows researchers to rigorously test competing hypotheses and determine which hold up under skeptical scrutiny.

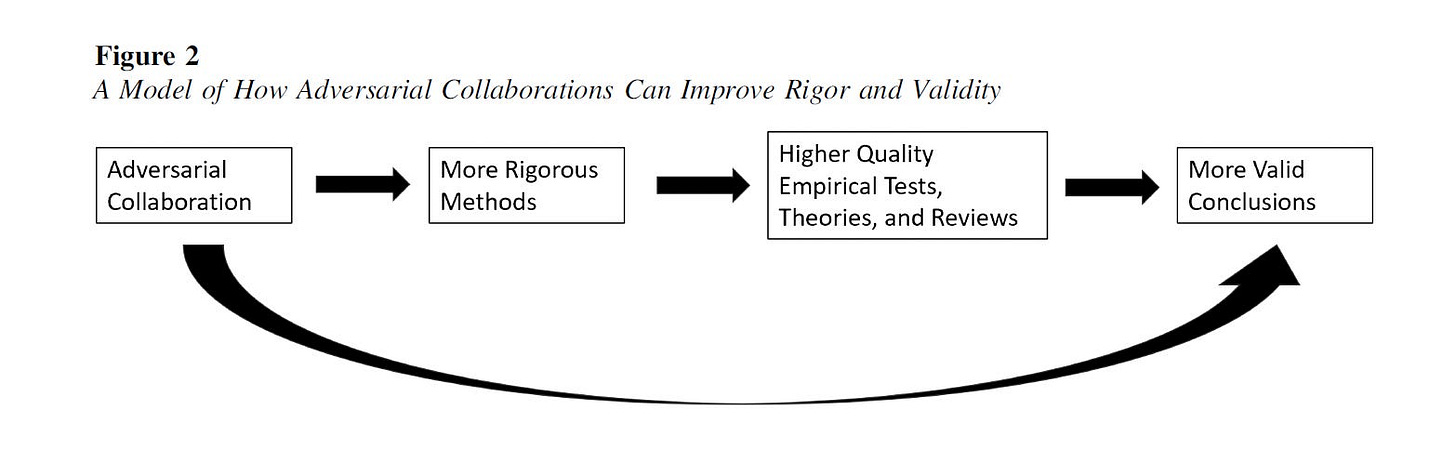

The process of strong inference – testing alternate hypotheses and designing experiments to exclude one or more and iterate on the survivors – is arguably the clearest and most efficient way to produce scientific advances. Typically, the alternative ideas necessary for strong inference emerge from different scientists who have different ideas about the nature of some phenomenon — this is viewpoint diversity. Furthermore, adversarial collaborations – research collaborations between scientists who have staked out opposing views on some phenomenon (viewpoint diversity rides again!) – are most likely to encourage strong inference. Opponents will be highly motivated to subject one another’s claims to severe tests – empirical tests likely to falsify some hypothesis if that hypothesis is actually false. As such, adversarial collaborations can provide an important check on the type of confirmation biases that can so often be found in peer reviewed literatures.

In sum, diversity of theoretical and political viewpoints is indispensable to scientific progress, especially its ability to weed out false claims when a question remains contested in the scientific community.

Yet there is a second, political benefit as well: viewpoint diversity is vital to reversing declining trust in higher education. A recent Pew poll shows that only 22% of Americans now believe a college degree is worth the cost if it requires student loans; many others distrust higher ed due to a perception of its excessively liberal bias. In such a climate, achieving greater ideological diversity among academics would not only strengthen scholarly rigor but also help restore public confidence – and the bipartisan support needed for sustained funding.7

The need for political and ideological diversity is especially urgent in fields where controversies center not on empirical facts but on values, ethics, and interpretation—as is common in much of the humanities and legal scholarship. In such domains, one-sided perspectives, when reinforced within echo chambers, can devolve into something resembling indoctrination. Such arguments can also grow flabby and untested because they rarely confront serious opposition. Without the pressure to engage opposing ideas rigorously, even well-intentioned advocates risk producing claims that crumble when exposed to scrutiny beyond the echo chamber. While a strong proponent of a view can sometimes represent alternatives fairly, the most reliable and robust source of counterarguments remains those who genuinely hold them.8

4. “There is no evidence that increasing ideological diversity will enhance the pursuit of truth, which is best safeguarded “locally” at the program level. The aims of viewpoint diversity and truth “directly conflict.””

Siraganian insists that ideological uniformity poses no threat to truth and that viewpoint pluralism would not help “resolve, or even address,” any academic debate. We have already largely debunked this in our response to her third claim, but Siraganian is wrong in yet additional ways which we elucidate here.

Contra Siraganian’s claim that academic echo chambers provide no threat to truth, robust evidence reveals how left-liberal predominance in the academy actively stifles scientific inquiry and open discussion on controversial questions:

Widespread self-censorship, especially among conservative and moderate scholars, is well documented.

Liberal faculty openly admit they would discriminate against conservative grant proposals, papers, or hires.

Scholars who express views on race, sex, gender, and colonialism that deviate from progressive norms or social-constructionist orthodoxy routinely face retraction, cancelation, backlash, or dismissal. For concrete examples, go here, here, here, here and here. For scholarly reviews of academics facing not criticism but punishment for expressing controversial ideas, go here, here or here. For examples of scholars who were ultimately vindicated despite facing this sort of academic mob-based censorship and punishment for challenging social justice shibboleths, go here and here.

Siraganian offers no grounds to contest such censorship – and may even embrace it – given her premise that only program-level “experts” are qualified to determine what counts as legitimate knowledge in these fields. That position does not hold up. Despite widespread academic rejection of biological sex as binary, scholars with comparable or sometimes stronger credentials than many advocates have mounted a robust case for the binary, gametic definition of sex (rooted in reproductive biology). Nonetheless, those scholars have faced not mere criticism, but denunciation and ostracism by activists and activist-scholars – exactly the type of social dynamic that stifles scientific progress. In an era of intensifying affective polarization and widespread self-censorship on contested issues, the public desperately needs trusted institutions capable of adjudicating sensitive questions rather than preemptively silencing them.

The principle of viewpoint diversity is a critical step in that regard. Siraganian is simply wrong to assert that ideological diversity bears no relevance to addressing academic debates. Increasing understanding of our “intuitive epistemology” shows that scholars necessarily bring their moral sensibilities into their interpretations of evidence. Consider the aforementioned surveys by Horowitz and colleagues, showing the predictive power of political ideology on scholars’ positions on a host of current controversies:

72% of liberal sociologists (vs. 37% of moderates) attribute inner-city Black poverty overwhelmingly to structural factors, downplaying cultural ones.

7% of liberal sociologists (vs. 25% of moderates) accept that biological differences may partly explain women’s underrepresentation in STEM.

9% of radical anthropologists (vs. 36% of moderates) find plausible the evolutionary psychological view that men evolved a greater instinct for sexual variety than women.

81% of liberal economists (vs. 27% of libertarians) believe corporate interests actively suppress renewable energy.

73% of radical economists (vs. 10% of libertarians) see monopoly as capitalism’s natural tendency.9

We cite these findings not to take sides in the debates, but to illustrate two points: 1. the palpable differences among professors’ views associated with their politics; and 2. when views conflict, as here, they cannot all be correct, which means that someone’s claims are unjustified political distortions. Just as a department of strictly libertarian economists may fail to adequately consider the ecological consequences of capitalism, we should not presume that left-wing sociologists alone are best positioned to assess the roots of urban poverty in the Black community. Controversies such as these are contentious (at least in part) because we do not have settled science to adjudicate them.

As bad as both scientific censorship and politically biased scholarship can be, yet a third problem is that, across a slew of social science areas, leftwing and activist political agendas have led to not just debatable claims, but demonstrably wrong conclusions and still worse, the canonization of wrong conclusions (see the Appendix for concrete examples). Because this work is now extensive, it is far too long to present in detail in this post, but I (Lee here) have begun drafting one or more Unsafe Science posts documenting this in detail.

Such cases make it all the more important for the academy to have adequate representation of the different viewpoints and to expose students to a range of scholars from diverse political standpoints.

This is not, however, what we have in higher ed today. Jon Shields and colleagues’ recent working paper attracted attention by showing the overwhelmingly one-sided readings assigned to students on controversial topics. After scanning millions of course syllabi, the authors found that in nearly all cases, students are disproportionately, and, in many cases, exclusively required to read progressive perspectives on racial disparities in incarceration, the ethics of abortion, or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. With debates raging on such matters in the wider culture, it is not hard to understand the impact of such ideological narrowness on public trust in higher ed.

Universities’ legitimacy crisis is real. It’s tempting to attribute it entirely to conservative attacks on higher education. Yet the right’s long campaign against universities – no matter how cynical or selectively outraged – does not absolve the academy of responsibility for its own missteps. Conservative critiques did not entirely emerge from thin air. As universities increasingly positioned themselves as engines of progressive activism, complete with climates of fear, self-censorship, and occasional outright censorship, they predictably alienated large swaths of the public. Moreover, criticism of this politicization has never been the exclusive province of the right. Scholars across the political spectrum, and especially on the left, have warned for decades about the dangers of turning campuses into ideological monocultures.

As early as 1915, the American Association of University Professors sounded an alarm that feels almost prophetic today:

If this profession should prove itself unwilling…to prevent the freedom which it claims in the name of science from being used as a shelter for inefficiency, for superficiality, or for uncritical and intemperate partisanship [emphasis added], it is certain that the task will be performed by others – by others who lack certain essential qualifications for performing it, and whose action is sure to breed suspicions and recurrent controversies deeply injurious to the internal order and the public standing of universities.

Critics like Lisa Siraganian (ironically, who heads the Johns Hopkins AAUP chapter, although the irony seems lost on the entire modern AAUP) who dismiss viewpoint diversity would do well to heed the 1915 AAUP’s warning. If higher education persists in its ideological insularity, the public will increasingly seek answers elsewhere – often from fringe, hyper-partisan, or outright conspiratorial sources. The result will not only spread misinformation but further entrench our national polarization.

None of this implies surrendering academic autonomy to govt-inflicted (and probably illegal) hiring quotas. How to increase the political diversity of academia is a difficult problem, and this essay is already long enough, so we do not address it here. Nonetheless, the goal of increasing political diversity is to widen the circle of contestation so that truth has a better chance of emerging and public trust can be rebuilt. It is not to achieve political “balance” for its own sake or to appease rightwing politicians.

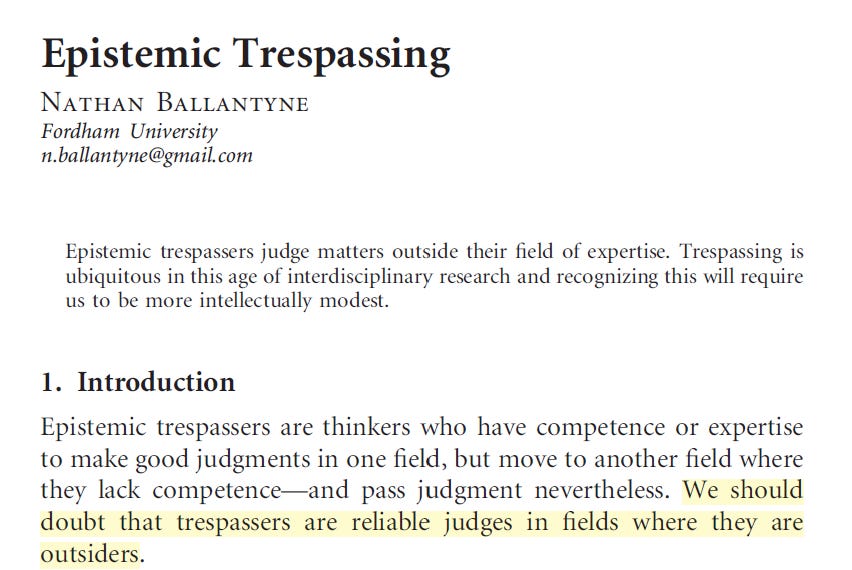

A Case Study in the Dangers of Epistemic Trespassing

Siraganian is a professor of comparative thought and literature, not a scientist. Her vita lists two bachelors and a masters degree in English and a JD law degree. Her scholarship includes titles like, “Art and Surrogate Personhood” and “Modernism and the Meaning of Corporate Persons.” This may all be exquisite scholarship for a Professor of Comparative Thought and Literature but if she has ever conducted empirical (social) scientific research, we have not found it. Of course, even if she has, it does not improve or justify her ideas about viewpoint diversity; in some ways, it would worsen her essays because she should have known better.

Nonetheless, just as your uncle the used car dealer is probably not the best source of advice on how to evaluate vaccines, English professors are probably not often the best sources of advice on how to conduct science. Epistemic trespassing is well-known in the philosophy literature as a prima facie basis for doubting anything being proclaimed by someone who lacks expertise to do said proclaiming.

The profound and repeated ignorance and confusion of how science works, the superficial strawmanning of arguments for viewpoint diversity, the confusion of the messenger with the message, all to be found in Siraganian’s essay, constitute an object lesson in how easy it is to go wrong when one trespasses in domains in which one lacks the relevant expertise.

Conclusion

To be sure, viewpoint diversity is not a panacea. Science and social science can go wrong for many reasons that have nothing to do with ideological capture. As Bloom notes, some departments legitimately coalesce around a shared method, perspective, or theoretical core, and forcing heterogeneity there could sometimes do more harm than good. Simply put, one can often get more accomplished working with like-minded colleagues than arguing with opponents, creating incentives for faculty to hire people who share their fundamental perspectives, interests, and values. But even Bloom acknowledges that increasing viewpoint diversity is probably a net benefit for academia as a whole. What we seem to have is a sort of collective action problem. There are often local disincentives for embracing viewpoint diversity despite it providing communal benefits.

In addition to improving scientific progress on politicized issues and restoring public trust in academia, viewpoint diversity can also improve teaching. Where students should encounter a range of credible perspectives on contested public questions – which is to say nearly always – intellectual diversity is an unambiguous strength. We urge everyone invested in the future of higher education to treat intellectual diversity as a serious reform priority. Academia needs to candidly acknowledge that, over the years, many have excluded ideas – and candidates in hiring decisions – more for ideological than scholarly reasons. We say this not to “lure” you in “bad faith,” as Siraganian alleges, but to increase the quality and rigor of scholarship and teaching.

We share her stated desire for good ideas to prevail and bad ones to wither. This is precisely why we are calling for greater ideological diversity in the academy — to create more skeptical checks on bad ideas that have regularly emerged from the leftist monoculture of academia on political and politicized topics; and to include a wider range of perspectives on political/politicized issues from which pertinent questions may be raised. Good ideas rarely flourish in echo chambers. No single ideological camp has a monopoly on truth, and the sooner the academy internalizes that humbling fact, the sooner it can begin to improve the quality of scholarship on unsettled politicized controversies, improve the quality of its teaching, and regain the public’s trust.

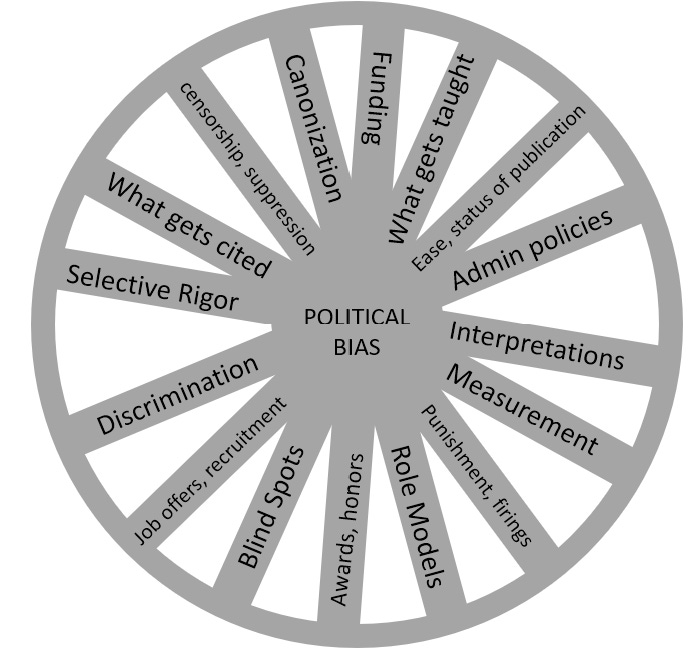

Appendix: An Incomplete List of Sources Demonstrating A Slew of Ways in Which Academia’s Political Biases Manifest, Including But Not Restricted to Wrong and Unjustified Scholarly Claims and Conclusions

The political bias wheel is an expansion of a model first presented here:

Honeycutt, N., & Jussim, L. (2020). A model of political bias in social science research. Psychological Inquiry, 31(1), 73-85. Reviews evidence of unjustified conclusions — all supporting leftist/progressive narratives — in a wide array of areas, including but not restricted to racial discrimination, implicit bias, sex bias, age stereotypes, stereotype threat, social class stereotypes, (in?)accuracy of stereotypes, and attributions of biases to conservatives versus liberals.

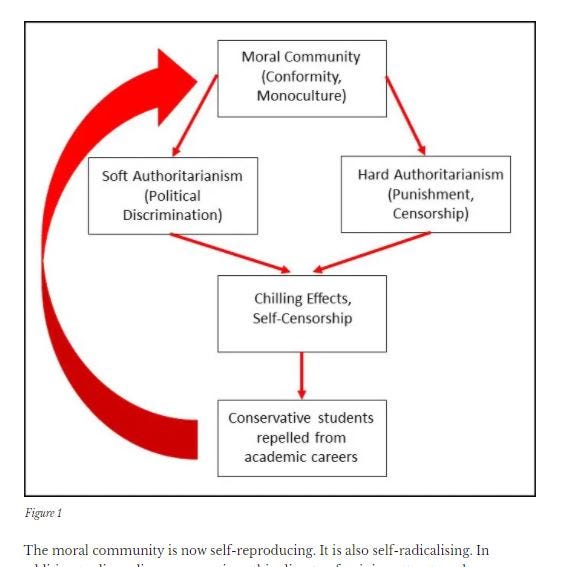

Model and massive supporting data from:

Kaufmann, E. (2021). Academic freedom in crisis: Punishment, political discrimination, and self-censorship. Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology, 2, 1-195.

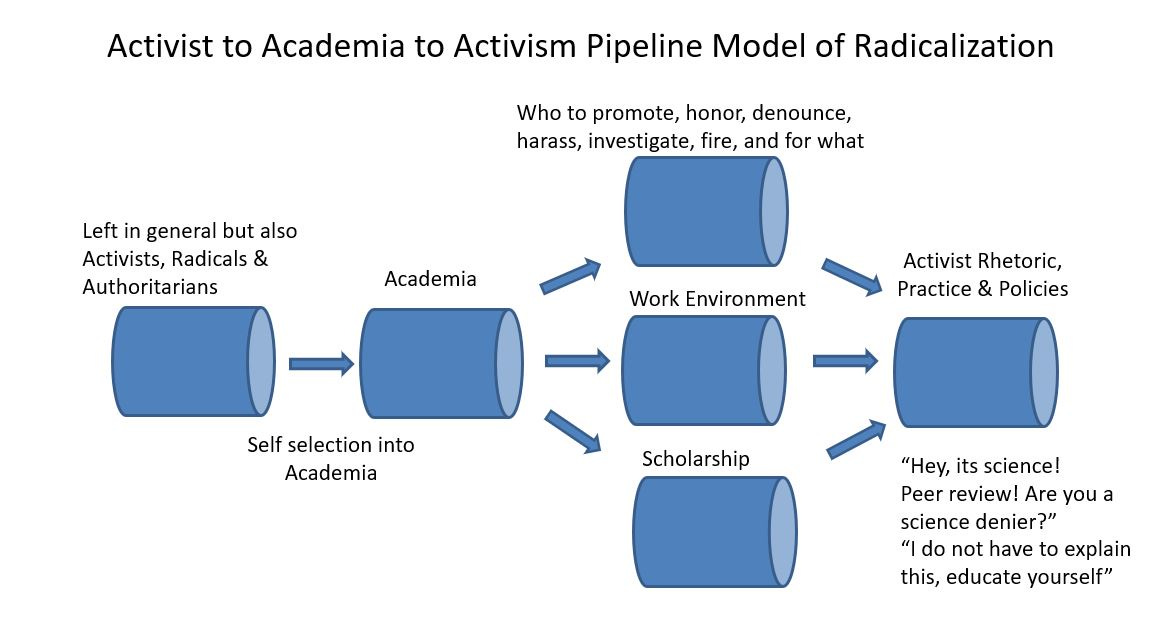

Model and massive data review from:

Honeycutt, N., & Jussim, L. (2023). Political bias in the social sciences: A critical, theoretical, and empirical review. Ideological and political bias in psychology: Nature, scope, and solutions, 97-146 (Frisby et al, editors).

Although there is way way more than this (as can be seen by consulting the references in the above sources), the following papers are particularly noteworthy:

Axt et al. (In press). On the relationship between indirect measures of Black vs. White racial attitudes and discriminatory outcomes: An adversarial collaboration using a sample of White Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Disconfirms almost every strong claims about “implicit bias” that they tested: 1. There was no anti-Black discrimination across four measures; 2. The predictive validity (for discrimination) of explicit measures was vastly higher than that of implicit measures; 3. The incremental validity of implicit measures (over explicit measures) was right on the threshold that the research team considered the smallest effect size to be practically important. As the authors put it:

Even an optimistic interpretation of the present work suggests severe limits to the standard approach of deploying individual indirect measures to predict specific behaviors of interest.

“Implicit bias” was once a common rhetorical tool used in crafting progressive narratives of oppression (how the U.S. is filled with unconscious bigots, especially but not exclusively racists) which are a primary source of inequality and various “gaps.” By disconfirming the bases for such claims, this research shows implicit bias narratives of oppression were unjustified — and making unjustified political/politicized claims constitutes one manifestation of political bias (see Jussim & Honeycutt 2023, below).

Bartels, J. M. (2023). Indoctrination in introduction to psychology. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 22(3), 226-236.

This paper reviews introductory psychology textbooks, and demonstrates how, in several areas, presentation of debunked areas that flatter progressive views proceeds as if those debunkings did not exist, and that the presentation of controversial areas often ignores the controversy simply by only presenting conclusions that support progressive narratives.

Bleske-Rechek, A., Savolainen, J. Meritorious disparities: AP exams and the academic pipeline to medicine. Theory and Society, 55, 5 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-025-09680-w.

From the article:

The denominator exercise underscores a general lesson: conclusions about “racial disparities” depend entirely on the baseline. When we use population denominators, disparities appear massive and can be attributed to systemic racism. When we use performance-based denominators, disparities reverse, revealing preferences for underrepresented groups. The reality is not exclusion but a shortage of high-performing candidates at the very start of the pipeline.

For decades, discussion of racial inequality in education and the professions has been framed around population-based disparities. If Group A makes up 14% of the general population but only 7% of medical graduates, the gap is treated as prima facie evidence of exclusion. That framing is not unique to education. It is the dominant mode in debates about policing, incarceration, employment, and nearly every domain where outcomes differ by group.

The difficulty is that population denominators obscure the role of preparation and performance. They measure disparities at the end of a pipeline without considering the composition at the start. In the case of AP Chemistry and medical education, the denominator choice is decisive: it changes the story from Asian overrepresentation and Black disadvantage to a finding that Asians are under-selected relative to performance and Blacks are favored.

Borjas, G. J., & Breznau, N. (2024). Ideological Bias in Estimates of the Impact of Immigration (No. w33274). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Preprint describing research in which pro & anti-immigration economists were unleashed on data and consistently found results … consistent with their political positions.

Burt, C. H. In press. Ideological Homogeneity and its Epistemic Discontents: A Case Study of Research on Transgender Issues. Theory & Society.

How transgender ideology insinuates itself into research methods and interpretations in ways that lead to manifestly false claims.

Efimov, I. R., Flier, J. S., George, R. P., Krylov, A. I., Maroja, L. S., Schaletzky, J., ... & Thompson, A. (2024). Politicizing science funding undermines public trust in science, academic freedom, and the unbiased generation of knowledge. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, 9, 1418065.

From the abstract:

When funding agencies politicize science by using their power to further a particular ideological agenda, they contribute to public mistrust in science. Hijacking science funding to promote DEI is thus a threat to our society.

Jussim, L., & Honeycutt, N. (2023). Psychology as science and as propaganda. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 22(3), 237-244.

We laid out a priori standards for evaluating whether some published paper is politically biased (=propaganda scholarship). Here are those criteria:

Test 0. Does the paper vindicate some ideological/political narrative?

This criterion is necessary because, if not making some political/ideological point, it can’t be politically/ideologically biased. It is not sufficient because the point may be accurate, valid, or justified. If Test 0 is passed, to constitute ideologically biased research it must also pass one of the following 3 tests.

Test 1. Did they misinterpret or misrepresent their results in ways that unjustifiably advance a particular politicized narrative?

Test 2: Do the authors systematically ignore papers and studies inconsistent with their

ideology-affirming conclusions?

Test 3: Did they leap to ideology-affirming conclusions based on weak data?

Note that these standards refer to characteristics of the scholarship, NOT characteristics of individual researchers. For more on this, see footnote 10.10

These standards are then applied to the areas reviewed by Bartels (2023, listed above). Areas that met one or more of those standards included: The Stanford Prison Experiment, Rosenhan’s Being Sane in Insane Places, implicit bias, stereotype threat, and multiple intelligences.

Mogilski, J., Jussim, L., Wilson, A., & Love, B. (2025). Defining diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) by the scientific (de) merits of its programming. Theory and Society, 54(6), 1173-1186.

Adversarial collaboration and brief yet broad review finding almost no

scientific evidence supporting either the benefits of most DEI programs as implemented throughout academia

attempts to evaluate negative side effects

attempts to evaluate whether the benefits (if any) justified either their financial costs or the effort involved in compliance.

Although the review does not address political bias directly, it supports the idea that the un- or weakly-evidenced yet widespread implementation of such programs throughout academia reflected administrators’ progressive political values, rather than programs based on sound, rigorous social science.

Rubin, A. T. (2025). Normativity is not a replacement for theory. Theory and Society, 1-56.

Rubin demonstrates how, in criminology, subtle normative shifts in language (often required to publish) smuggle in unjustified or debatable progressive conclusions about the (in)justice of the U.S. legal system and how description of phenomena is being replaced with prescriptions, often based on contested, weak or nonexistent evidence justifying those prescriptions

Schaerer, M. (Michael); Du-Plessis, C. (Christilene); Nguyen, M.H.B. (My Hoang Bao); et al. "On the trajectory of discrimination: A meta-analysis and forecasting survey capturing 44 years of field experiments on gender and hiring decisions". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 179, 2023-11-10, 104280.

Contra social justice narratives about pervasive sex discrimination in hiring, meta-analysis of experimental audit studies finds more biases against men than women since 2009 (and little or no bias before that). Tellingly, it also found that the academics they surveyed predicted the meta-analysis would find substantial evidence of biases against women — apparently, academics, even those with expertise in gender issues (who they examined separately and among whom they found the same pattern), do not know the findings of the literature they were supposedly expert in. One can only imagine what they have been teaching to undergraduates and their research mentees.

Shields, J. A., Avnur, Y. & Muravchik, S. (2025). Professors need to diversify their syllabi. Persuasion.

They obtained millions of college syllabi, and found that progressive sources emphasizing pervasive racism and anti-Zionist perspectives on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict were assigned massively more often than comparably high (or, in some cases, higher quality) academic sources contesting those views. Whether this is intentional indoctrination or unintentionally negligent malpractice hardly matters.

Zigerell, L. J. (2018). Black and White discrimination in the United States: Evidence from an archive of survey experiment studies. Research & Politics, 5(1), 2053168017753862.

Zigerell examined 17 unpublished studies using NSF TESS data that addressed racial discrimination. From the abstract:

For White participants (n=10 435), pooled results did not detect a net discrimination for or against White targets, but, for Black participants (n=2781), pooled results indicated the presence of a small-to-moderate net discrimination in favor of Black targets…

Zigerell’s findings raise the question, Why weren’t these results published? Whether this was because the researchers chose not to do so, or they tried but could not, it is clear that such findings contest narratives about pervasive racial discrimination in the U.S. — and, one way or another, such a finding is readily interpretable as political publication biases.

Commenting

Before commenting, please review my commenting guidelines. They will prevent your comments from being deleted. Here are the core ideas:

Don’t attack or insult the author or other commenters.

Stay relevant to the post.

Keep it short.

Do not dominate a comment thread.

Do not mindread, its a loser’s game.

Don’t tell me how to run Unsafe Science or what to post. (Guest essays are welcome and inquiries about doing one should be submitted by email).

Footnotes

Both of us are members of Heterodox Academy and Horowitz is a member of AAUP.

Mill, on viewpoint diversity.

Mill argued that people should be permitted to propound even terribly wrong ideas for three reasons: 1. Just because we think they are wrong, does not mean they are wrong. Maybe we are wrong. The only way to find out is to allow the ideas to clash; 2. Even if we are mostly right, maybe there is some truth in the ideas we think “wrong,” and it is through the clash of viewpoints that our own ideas can become less wrong and more right; 3. Even if we are 100% right and our opponents 100% wrong, if we permit their views to be expressed, they can be debunked; if we do not permit them to be expressed, over time, a society can forget why the wrong ideas are wrong and be unable to refute them.

“Diversity,” in 1978, had only one meaning: variety. In Bakke, SCOTUS legalized the use of race in admissions as only one of many different types of diversity that universities were justified in seeking. And what powered the justices’ opinion was the educational value of viewpoint diversity. Progressives saw that loophole, created a whole second meaning for the word “diversity” (“oppressed groups”), and then proceeded with a bait and switch: to act as if SCOTUS’s use of “diversity” meant “oppressed groups” rather than the viewpoint diversity that they actually meant. Consequently, they never adopted policies for the purpose of increasing diversity** other than for groups they deemed oppressed, a story presented here in gory detail, including tracing the history of the meaning of the word “diversity” and extensive quotes from Bakke and the 2003 Grutter decision that also permitted racial preferences in the name of diversity:

** In the original meaning of diversity.

In Bakke, SCOTUS completely rejected social justice type reasons for permitting racial discrimination in admissions. From that decision:

Petitioner urges us to adopt for the first time a more restrictive view of the Equal Protection Clause, and hold that discrimination against members of the white “majority” cannot be suspect if its purpose can be characterized as “benign.” [p295] The clock of our liberties, however, cannot be turned back to 1868. Brown v. Board of Education, supra at 492; accord, Loving v. Virginia supra at 9. It is far too late to argue that the guarantee of equal protection to all persons permits the recognition of special wards entitled to a degree of protection greater than that accorded others.

… the difficulties entailed in varying the level of judicial review according to a perceived “preferred” status of a particular racial or ethnic minority are intractable. The concepts of “majority” and “minority” necessarily reflect temporary arrangements and political judgments. As observed above, the white “majority” itself is composed of various minority groups, most of which can lay claim to a history of prior discrimination at the hands of the State and private individuals. Not all of these groups can receive preferential treatment and corresponding judicial tolerance of distinctions drawn in terms of race and nationality, for then the only “majority” left would be a new minority of white AngloSaxon Protestants. There is no principled basis for deciding which groups would merit “heightened judicial solicitude” and which would not. Courts would be asked to evaluate the extent of the prejudice and consequent harm suffered by various minority groups. Those whose societal injury is thought to exceed some arbitrary level of tolerability then would be entitled to preferential classifications at the expense of individuals belonging to other groups. Those classifications would be free from exacting judicial scrutiny.

As these preferences began to have their desired effect, and the consequences of past discrimination were undone, new judicial rankings would be necessary. The kind of variable sociological and political analysis necessary to produce such rankings simply does not lie within the judicial competence even if they otherwise were politically feasible and socially desirable.

Third, there is a measure of inequity in forcing innocent persons in respondent’s position to bear the burdens of redressing grievances not of their making.

We have never approved a classification that aids persons perceived as members of relatively victimized groups at the expense of other innocent individuals in the absence of judicial, legislative, or administrative findings of constitutional or statutory violations.

Hence, the purpose of helping certain groups whom the faculty of the Davis Medical School perceived as victims of “societal discrimination” does not justify a classification that imposes disadvantages upon persons like respondent, who bear no responsibility for whatever harm the beneficiaries of the special admissions program are thought to have suffered. To hold otherwise would be to convert a remedy heretofore reserved for violations of legal rights into a privilege that all institutions throughout the Nation could grant at their pleasure to whatever groups are perceived as victims of societal discrimination. That is a step we have never approved.

Democrats seem like Communists to a rightwing ideologue and Republicans seem like fascists to a leftwing ideologue. This does not mean every such accusation is necessarily wrong. Trump’s policies have been described as illiberal, authoritarian or fascist by an increasing number of critics who are most definitely not leftwing ideologues (e.g., here or here). And, if not quite a fullblown Communist, a self-proclaimed socialist now governs New York City, and another is senator from Vermont.

Where viewpoint diversity matters most for rigorous scholarship. Although political biases are much less likely to infect math and the natural sciences than the humanities and social sciences, such infection has indeed occurred. Furthermore, the political makeup of even the natural sciences can create skewed support for politically controversial policies within academia, such as implementation of DEI programs and support for censorship.

On the politics of academia necessary to sustain funding. As philosopher Matt Lutz put it here at Unsafe Science: “Here is the bottom line. Simple, incontestable fact: Academia cannot continue to function with anything like its current funding model as long as it remains a partisan political institution. And a corollary: academia will not receive the kind of support that it has enjoyed since the GI bill unless it reforms to become the kind of institution that Republicans can happily support.”

The most reliable and robust source of counterarguments remains those who genuinely hold them. Also from JS Mill (writing 100ish years before Horowitz was born):

He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side, if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion. Nor is it enough that he should hear the opinions of adversaries from his own teachers, presented as they state them, and accompanied by what they offer as refutations. He must be able to hear them from persons who actually believe them; who defend them in earnest, and do their very utmost for them. He must know them in their most plausible and persuasive form; he must feel the whole force of the difficulty which the true view of the subject has to encounter and dispose of; else he will never really possess himself of the portion of truth which meets and removes that difficulty.

Horowitz’s survey, and comparisons of left academics to moderates or libertarians. Did you notice what was missing? … We’ll wait … Can you figure it out? … Here comes the answer — conservatives! Why? Because there were too few conservative academics in these surveys on which to base meaningful comparisons.

“These standards refer to characteristics of the scholarship, NOT characteristics of individual researchers.” From Jussim & Honey (2023):

Some researchers seem to define “political bias” as some sort of individual characteristic of scientists, for example, that they have an ideology and interpret and slant their scholarship accordingly. In an essay titled, “You Too Have an Ideology” Syed (2023) correctly pointed out that most scientists have ideologies and that this can inform and bias their work. From our perspective, this is a brilliant political rhetorical move, because it absolves researchers from having to take their own political bias seriously, largely on the grounds that “everyone is biased.” It is probably even more problematic, because rather than being taken as a warning to engage in strong practices to limit biases, it risks liberating researchers to inflict their biases on their scholarship, on the grounds that not only is everyone biased but also “my biases are better than yours.” Despite its rhetorical brilliance, such a perspective, by potentially glorifying infliction of the “right” biases on scholarship, is scientifically corrupt.

It is surely true that everyone is biased about some things, but that does not mean every researcher engages in the uninhibited infliction of their biases on their scholarship. If A (political motivations) can cause B (political bias) then A and B must be different things. This is important because a researcher may have political motivations and not act on them in ways that distort their conclusions (A does not necessarily cause B). Similarly, a researcher may produce politically biased conclusions in the absence of political motivations (other things besides A can cause B).

Consider hypothetical researchers who believe that most of their colleagues favor work that has a veneer of antiracism. Such researchers may then conclude, “If I interpret and promote my work as anti-racist, it may be more likely to be published, cited, and lauded.” The motivation to publish and advance one’s career, rather than personal politics, may lead these researchers to highlight the antiracist nature of the work. Putting aside whether simply framing something in this manner can be a form of bias, it becomes a scientific distortion if the researchers highlight ways in which the work is antiracist that are not supported by their own data (the IAT, multiple intelligence, and stereotype threat examples all include scholarship advocating antiracist claims not supported by the published data).

This analysis is not restricted to antiracist claims; it applies anytime researchers believe professional processes incentivize any politicized claim. Our analysis is also not restricted to incentives. Anytime professional processes favor the production of unjustified claims supporting one ideology for any reason, a literature will likely become biased. In principle, these processes apply equally to left- and right-biased claims, but because of the extreme political skew of academia, this will be primarily left-biased.

Thus, when we use the term “political bias,” we rarely refer to characteristics of individual researchers. Instead, we use the term “political bias” to characterize scientific literature that systematically and erroneously canonizes and emphasizes dubious or false left-affirming claims and/or systematically fails to recognize evidence and rigorous conceptual and statistical analysis that contests those claims

What's fascinating to me is that the AAUP didn't seem to recognize a priori that the essay in question was probably going to do more harm to academia's case than anything Trump, Horowitz, or MAGA - all convenient boogeymen - could ever have done on their own. It's almost like someone snuck in and replaced their progressivism playbook with one aptly titled "How to keep shooting ourselves in the foot." I've seen some cases against viewpoint diversity (Paul Bloom recently wrote one) that are reasoned, but the essay in question - at AAUP's flagshit publication - reads like something out of a drug-induced conspiracy theory. It's a laughable argument, though I appreciate you takedown of it. Keep up the good work.

Thanks for this timely essay and rejoinder to Siraganian. I share your concerns about the parlous state of academia in terms of (lack of) viewpoint diversity.

I am interested in your point about “epistemic trespassing”. As a retired doctor with a strong interest in bioethics, I’m deeply concerned about the practice of paediatric gender medicine. I’m obviously not an “expert” but I have read The Cass Review and The HHS Review, along with bioethics literature from both sides of the gender debate.

However, gender activists and clinicians use the idea of epistemic trespassing to assert that only gender clinicians working in the field of PGM have the knowledge and experience to be trusted to act in children’s best interests. Everyone with countervailing views is automatically assumed to be motivated by transphobia or fundamentalist religious beliefs.

But as far as I’m aware it’s impossible to be a gender clinician unless you buy into the “affirmation model” of gender identity. So the idea of epistemic trespassing creates a Catch 22 situation that makes it very difficult to critique PGM.