In this essay, I explain why, if the only thing you know is that something is published in a psychology peer reviewed journal, or book or book chapter, or presented at a conference, you should simply disbelieve it, pending confirmation by multiple independent researchers in the future.1

Here are the key ideas:2

Equation 1:

%False Claims = (%Unreplicable Findings) + (%References to Unreplicable Findings as If They are True) + (%False Claims Based on Replicable Findings) + (%False Claims Based on Ignoring Contrary Evidence) + (%False Claims Due to Censorship) + (%False Claims Based on Making Shit Up Completely)

% here means “percent of claims in the literature.” The denominator is hypothetical (i..e., not known) but is “the entire psychology literature.” For example, %False Claims refers to the proportion of claims in the psychology literature that are false, out of all claims in that literature. All %False claims [due to X] referred to here are, therefore, out of the entire psychology literature.

In the remainder of this essay, I do provide an empirical basis for %Unreplicable Findings, but do not do so for the remaining components of Equation 1. Instead, I present existence proofs for each of the components of the equation shown in Equation 1. Thus, it will be clearly established that all remaining components of Equation 1 are above 0. I end by justifying why ~75% is a plausible, though not definitive, estimate.

As shall seen below, the run rate for Unreplicable Findings alone is about 50%. That sort of gives a running start toward an estimate that 75% of what appears in the psych literature is wrong.

But first, some qualifications. I am not counting claims for things that are entirely obvious without the benefit of the psychological “scholarship.” So if a paper claims the sky is blue or refers to well-documented historical events (U.S. presidents, wars, etc.), I am not counting it as a psychological scholarship claim. I am only counting psychological claims that either are or should be based on empirical research in psychology.

Second, I distinguish between mere descriptions of others’ research, which is so simple it is not worth counting, from wild overgeneralizations based on that research, which I do count. For example, the statement “Kang & Banaji (2006) claimed that 75% of White Americans show anti-Black bias” is an accurate description of what they stated. But it is so simple to simply summarize others’ claims that I count it no more than “the sky is blue.” On the other hand, the statement “75% of White Americans are unconscious racists (Kang & Banaji, 2006)” would be a wildly inaccurate overstatement that I would indeed count as wrong.

And third … How does one know when a scientific claim has been established with sufficient credibility to warrant treating it as a fact? This is important because all published papers that make a claim that rises to the level of fact do not contribute to Equation 1. So they must all be excluded. To be excluded, I must have criteria for doing so, which I next articulate.

What are Scientific Facts?

Something is not a fact just because some scientist or article says so, whether on social media or in a peer reviewed publication. I find the definition provided by the late evolutionary biologist, Stephen Jay Gould (1981) particularly useful: “In science, ‘fact’ can only mean ‘confirmed to such a degree that it would be perverse to withhold provisional assent.” This is worth unpacking in reverse order. “Provisional assent” means that, in principle, most scientific claims are subject to change if overwhelming evidence is provided overturning some “established” conclusion. But doing so is not easy because when there is a mountain of evidence that some claim is true, withholding provisional assent is perverse. “Perverse” in this context means rigidly dogmatically clinging to a belief when there is a mountain of evidence demonstrating otherwise. It is, in the 21st century, perverse to believe that the Earth is flat, that women are, on average, taller than men, or that SAT scores are, on average, identical across American racial/ethnic groups (although the meaning and sources of those differences are hotly contested).

I rely on Gould’s definition here. However, we also articulated this corollary in a chapter on scientific gullibility (why scientists believe and have promoted bad, dumb ideas, Jussim, Stevens, et al., 2019, p. 281): “Anything not so well established that it would not be perverse to withhold provisional assent is not an established scientific fact.” So when scientists promote ideas as true that have, at best, weak logical or empirical foundations, they are bullshitting.3 More important, their claims are not facts.

Different Types of Inaccurate Claims in Scholarship

A claim (including but not restricted to published claims) can be inaccurate in any of a variety of ways. It can be false, in that there is ample reason to know that the claim is untrue. Claiming that the Earth is flat is false. Claims can also be inaccurate because they are unjustified by the evidence. Unjustified scientific claims occur when a truth-claim is made in a scientific context (journal article, chapter, research talk, poster, etc.):

● without presenting or citing any evidence

● that cites a source that has been debunked or which has reported a finding that others have been unable to replicate.

● that cites a source that itself makes the claim but presents no evidence for it

● that cites a source that presents evidence that does not bear on that truth claim

● that cites a source that presents evidence that it claims as support, but the evidence fails to actually support it (by virtue of low rigor, measures of dubious validity, failure to rule out alternative explanations, etc.).

For example, claiming that Mars once had life is not known to be false because it is possible. But, at present, there is no conclusive evidence that Mars actually once had life on it. Whereas speculating about the possibility of life on Mars is reasonable, claiming (or implying) that it is a scientific fact that life once existed on Mars is unjustified and is treated as false in this essay.

Claims are also treated here as false when they present an incomplete and distorted view of the evidence. These claims are not without evidentiary support because, in these cases, there is some evidence supporting the claim. For example, if one was to claim that New Jersey is colder than Alaska, this would be false. Even if one could identify days in which the high temperature was colder somewhere in N.J. than somewhere in Alaska, claiming that New Jersey is generally colder than Alaska is still false. By cherrypicking the “right” day, one might present “evidence” supporting the claim that New Jersey is colder than Alaska, but the claim is misinformation because, in general, Alaska is colder than New Jersey. This is obvious, but it applies to claims appearing in scholarship based on selective reporting and citation of evidence as well.

Most of Psychology Has Not Established Scientific Facts

The Replication Crisis

Publication ≠ scientific fact; p<.05 ≠ scientific fact. The Replication Crisis refers to the panic that ensued when psychologists discovered that many of their most cherished findings could not be replicated by independent teams (see, e.g., Nelson et al., 2018, for a review). This was labeled a “crisis” as opposed to “normal operating procedure” because, apparently, many of the field’s most famous researchers implicitly ascribed to “scientism” rather than to a “scientific” view of psychological research. As we discussed in our Scientific Gullibility chapter (Jussim, Stevens, et al., 2019, p. 284):

Scientism refers to an exaggerated faith in the products of science (findings, evidence, conclusions, etc…). One particular manifestation of excess scientism is reification of a conclusion based on its having been published in a peer reviewed journal. These arguments are plausibly interpretable as drawing an equivalence between “peer reviewed publication” and “so well established that it would be perverse to believe otherwise”... They are sometimes accompanied with suggestions that those who criticize such work are either malicious or incompetent… and thus reflect exactly this sort of excess scientism.

And on p. 285:

There are two bottom lines here. Treating conclusions as facts because they appear in peer-reviewed journals is not justified. Treating findings as ‘real’ or ‘credible’ simply because they obtained p < .054 is not justified.”

Had there been a wider understanding that publication in a peer reviewed journal and p<.05 do not constitute establishment of scientific facts in the Gouldian sense, no one would have treated such studies as having done so. They would have been treated as preliminary and speculative so that failed replications would have been shrugged off as normal. But because prestigious scientists had made entire careers producing cute, dramatic, small sample studies around which they could tell amazing, dramatic stories! (see Jussim et al., 2016, for a review), they and much of the field of psychology labored under the misimpression that they had established new scientific facts. And so failed replications of their studies became a “crisis.”

The replication base-rate = a coin flip. In this context, it was then not surprising that the long-term success rate for replications in psychology has hovered right around 50% (e.g., Boyce et al., 2023; Open Science Collaboration, 2015; Scheel et al., 2021). No one would declare it to be a “fact” that a (balanced) coin flip generally comes up heads. Although this is obvious, then so is the implication that no one should be declaring something a fact just because it has been published in the peer reviewed psychology literature, which, historically, has stood about a 50-50 chance of being replicable. This figure shows registered replication reports5 successfully replicating prior studies only about 1/3 of the time, but some of the other papers (cited in this paragraph) show higher replication rates, but rarely much above 50%. I am probably being too generous to my field by ballparking the successful replication rate at about 50%, so, if anything, the state of affairs is probably even worse than I am concluding here.

Building the Estimate Toward 75%

So the baseline of outright failed replication attempts is about 50%. Maybe higher. It is possible that some small subset of these will be replicated by future research, but, for now, no one has any reason to take the ~50% of studies that others could not replicate seriously. Colloquially, the replication crisis results means that, out the gate, half of psych findings are best considered “wrong” till further notice.

That’s the good news.

The Literature is Filled with Papers that Simply Ignore the Failed Replications

Failed replications have little detectable effect on citations to the original study. Serra-Garcia and Gneezy (2021, abstract), put it this way:

…published papers in top psychology, economics, and general interest journals that fail to replicate are cited more than those that replicate. This difference in citation does not change after the publication of the failure to replicate. Only 12% of postreplication citations of nonreplicable findings acknowledge the replication failure.

Thus, academic publishing generally proceeds (88% of the time as per their findings) as if the failed replications do not even exist. We have reported similar results on a smaller scale in several papers over the years, this is adapted from a table in a paper from 2016:

The final column is amazing in an appalling sort of way: the study others cannot replicate remains cited massively more often than the failed replication years after the failed replication was published, as if the failed replications do not exist. This is professional incompetence writ large. Citing the original unreplicated study as if it is true, after failed replications, is promoting misleading information at best. Only the gods know how often zombie claims based on papers others cannot replicate appear in the peer reviewed/academic literatures.

Therefore, this increases the proportion of false claims in the literatue above 50% to some unclear degree.

%False Claims = (%Unreplicable Findings) + (%References to Unreplicable Findings as If They are True)

We have a plausible estimate for Unreplicable Findings (50%). We do not have one for References to Them. But it is clearly above 0. So Something More Than 50% of the Claims in Psych are False.

But…

50% Replicates, But are Claims Based on Replicable Findings Necessarily True?

No no no, a thousand times no. Replication is just the start. Consider a simple example:

If you leave bread out for awhile, it will usually grow mold. Bread growing mold is highly replicable, anyone can do this at home and (usually unintentionally) most of us have. Before microscopes and all that, this was construed as support for “spontaneous generation of life,” the idea that life routinely arises from inanimate matter.

The conclusion is completely wrong. The result is massively replicable. Therefore, that something is “replicable” most assuredly does not mean that any and all claims based on that replicable finding are true. Some are, most assuredly, very much not true. So even a replicable study may have some true statements (“the bread grew mold”) and some false ones (“this is evidence for spontaneous generation of life”). Some claims based on replicable studies are false.

Now let’s only consider some actual modern ridiculous claims based on some highly replicable psychology findings.

Implicit “Bias”

Just about everyone (including me) who conducts an implicit association test finds that people take longer to sort words into Black/pleasant and White/unpleasant than into Black/unpleasant and White/pleasant (or variations thereof, e.g., replacing pleasant/unpleasant with good/bad, smart/dumb, etc.). But the implicit bias literature is filled with manifestly false claims such as:

80% or more of Americans are unconscious racists.

The IAT measures introspectively unidentified effects of past experience that mediate discrimination.

The IAT measures “implicit bias.”

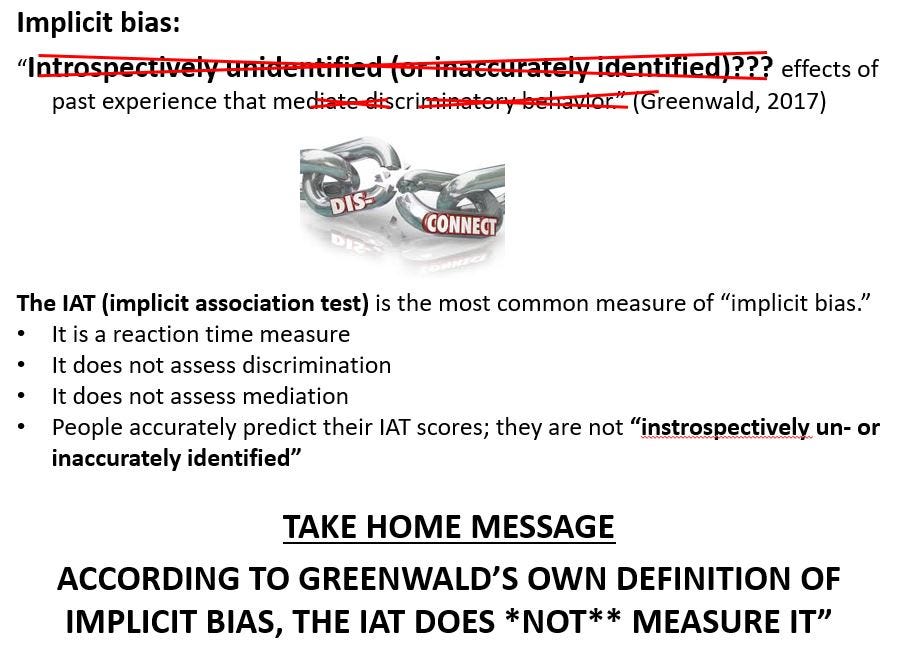

Below is a definition of “implicit bias” provided by Anthony Greenwald, creator of the IAT (implicit association test) at a special 2017 conference held by the National Science Foundation on the controversies surrounding implicit bias. He presented this as the working definition of implicit bias from 1998 to 2017. I have taken the liberty of crossing out the features of his definition that are knowably false or even ridiculous.

The IAT does not measure any type of bias, let alone an “implicit” one (whatever that means). It measures reaction times — how quickly people complete a word-association task. Ideally, it measures associations between concepts in memory, but there is no universe in which it is reasonable to consider associations any sort of bias, let alone discrimination.

IAT scores are not “introspectively unidentified.” People can predict their IAT scores to the tune of about correlations of .70, which makes this relationship one of the largest in social psychology.

The IAT is one variable. Whether it “mediates” anything, let alone “effects of past experience on discrimination” requires evidence, which is not provided by Greenwald’s or anyone else’s definition. Mediation requires three variables: A==>B==>C means B mediates the effects of A on C. A single variable, by itself, constitutes mediation of nothing. IAT scores are a single variable.

It gets worse. IAT advocates assume IAT scores of 0 reflect unbiased or egalitarian responses. There is no evidence for this and there is evidence that scores well above 0 corresponding to egalitarianism, though whether this is always or usually true is unknown, because precious few published studies bother to report the IAT score that corresponds to egalitarianism in those studies.

It continues to get worse. Estimates common to the IAT literature, that 80% or so of Americans are unconscious racists (putting aside that scores are not unconscious) are based on IAT scores above 0. But if 0 is not egalitarian and scores well above 0 are egalitarian, these estimates are wildly inflated.

My review article linked above (again, here) goes through all this; but why trust me? Here is a repository of over 40 sources, 90% NOT by me, most peer review or scholarly review chapters, but also a handful of blogs and one superb podcast that lay out the many many many (did I say “many”?) flaws and limitations to work on “implicit bias” and the many ways its major claims have had to be majorly walked back.

IAT scores are, however, massively replicable. This means that research using the IAT has routinely reported lots of false claims, despite it being replicable.

%False Claims = (%Unreplicable Findings) + (%References to Unreplicable Findings as If They are True) + (%False claims based on replicable findings).

We are now well above 50% false claims in the literature. But…

Interregnum

Let’s take stock. The point of the above section on IAT is not to imply that it is the only area of research that has produced replicable results but unjustified claims and interpretations of that research. There are many many other similar areas. If the IAT is the King of Replicable Research That Has Produced False Claims then microaggression research is the Crown Prince (see here, here, here, and here). But it does not end there. Hell, in 2016, I had an entire article published titled “Interpretations and Methods: Towards a More Effectively Self-Correcting Social Psychology” that goes through example after example after example after example of demonstrably wrong interpretations of empirical findings, including but not restricted to the so-called “power of the situation,” the role of motivation in perception, stereotype threat, unjustifiably interpreting gender gaps in graduate admissions as discrimination and many more.

Now we have:

%False Claims = (%Unreplicable Findings) + (%References to Unreplicable Findings as If They are True) + (%False Claims Based on Replicable Findings). We are now probably well above 50% of the claims are false, but…

False Claims Based on Ignoring Contrary Evidence

References to unreplicable findings as if they are true are actually a subset of false claims based on ignoring contrary evidence. But being that I have already accounted for those, this category needs to be completely different.

And it is. Sometimes, sets of studies are on the same topic or test the same hypothesis, but are conducted using different methodologies. Therefore, they are not replication studies. For example studies of racial, gender, or religious discrimination might be conducted in laboratories, college campuses, nonacademic workplaces, or academic workplaces. Some may study entry level jobs; others may study professional positions. These studies are too different from one another to be considered replications.

Consider for example Moss-Racusin et al. (2012, hence M-R) versus Williams & Ceci (2015, hence W&C). M-R found gender biases favoring men over women applying for a lab manager position in science fields. W&C found biases favoring women over men applying for a faculty position in STEM fields. These findings clearly conflict, that conflict should be acknowledged in scientific articles, and that conflict should dramatically reduce anyone’s confidence that gender biases consistently favor one sex over the other. But that is not how the field has been operating.

This is an adaption of a table reported in Honeycutt & Jussim, 2020:

This means that, as of 12/9/19, nearly 1200 papers cited M-R without even acknowledging the existence of W&C. I reconducted the “since 2015” portion of this analysis today (“since 2015” is used because that was when W&C was published, no one could cite it befor it was published). M-R has been cited 3930 times, W&C 546. That means, as of today, M-R has been cited by almost 3400 papers that simply ignored W&C. I have long argued that:

An unpublished project by one of my former honors students sampled papers citing only M-R and found that about 3/4 referred to it uncritically, i.e., taking its finding of gender bias at face value without doubt or uncertainty.

Lest one think we simply cherrypicked these two papers to fit our conclusion, Honeycutt & I (in that same 2020 paper linked above) tracked down every empirical study of gender bias in any sort of peer review we could find (e.g., hiring, publication, grant funding, etc.), and then compared sample sizes and citation counts based on whether they did or did not find biases against women. This table ignores papers finding unclear or inconsistent patterns of bias. Here is what we found:

Despite the research finding unbiased responding or biases favoring women using far more rigorous (i.e. larger) sample sizes, the research finding biases against women was cited more than five times as often. Put differently, about 80% of the literature reviewed here emphasized biases against women as if the larger and more rigorous studies finding no such biases did not exist.

This is peer reviewed bullshit of a high order. And, duh, this relentless “scientific” drumbeat of biases against women has led academics to vastly overestimate the actual level of biases against women in hiring!6

Once again, gender bias is just one example; there are many more like this (for examples, see here, here, here, here, and here).

Now we have:

%False Claims = (%Unreplicable Findings) + (%References to Unreplicable Findings as If They are True) + (%False Claims Based on Replicable Findings) + (%False Claims Due to Ignoring Contradictory Evidence). But…

False Claims due to Censorship, Including Self-Censorship

As we pointed out in our paper on scientific censorship, social pressure (which includes but is not restricted to censorship) can distory an entire literature. This figure shows how:

This figure shows a hypothetical “scientific” literature (the small circle) embedded within the state of affairs in the wider world (the big circle). Green stars are evidence that some claim is true; red stars are evidence that it is false. The “scientific” literature is filled with evidence that the claim is true even though, in the wider world, there is far more evidence that it is false. How can this happen? If there is social pressure to avoid saying the claim is false, scientists may publish far less evidence that the claim is false than that it is true.

This, however, was a mere description of how censorship could work. Is there any evidence that this has actually happened? Yes indeedy.

Zigerell found 17 NSF funded studies that tested for racial bias and found none — most of which was never published. We don’t know why the findings were never published. Did the researchers try to publish them but fail? Did they not try to publish them because they did not think the finding was important? Did they not try to publish them because they thought doing so would be too difficult (e.g., because they anticipated reviewers despising the result)? We do not know. All we know is that they did not publish these findings.

Bottom line: The published literature has far less evidence of no racial bias than it should. So, yes, our analysis (which was really Joshi’s analysis which originally appeared here) is not merely hypothetical. To some extent, claims in the literature about racial bias are inaccurate because these findings were never published.

This is not restricted to studies of racial bias. Publications criticizing Diversity, Equity and Inclusion initiatives evoked academic outrage mobs which, until recently, consistently succeeded in getting those papers retracted. Indeed, papers that offend progressive sensibilities on a variety of topics, including transgender issues, colonialism and racial biases (or the lack thereof) in policing have all been retracted (see, e.g., here or our chapter, The New Book Burners, which can be found in this book). Indeed, this pattern of forced retraction for offending progressive sensibilities raises more general questions about how much the social scientific literature overstates support for progressive views more broadly — if academics have “gotten the message” that you risk unleashing Hell if you cross progressives, they may self-censor way beyond what has been documented here.

Now we have:

%False Claims = (%Unreplicable Findings) + (%References to Unreplicable Findings as If They are True) + (%False Claims Based on Replicable Findings) + (%False Claims Based on Ignoring Contrary Evidence) + (%False Claims Due to Censorship).

And yet…

Making Shit Up Completely

Many claims that appear in the peer reviewed literature are not even based on data, let alone replicable studies. My favorite in this category are claims about the inaccuracy of stereotypes. These are typically made by either:

Stating so, with no citation to evidence at all.

Citing a paper that also makes the claim but which has no evidence.

Consider some once common claims about stereotypes, all of which can be found and sourced in my 2012 book:

"However, a great deal of the thrust of stereotyping research has been to demonstrate that these behavioral expectancies are overgeneralized and inaccurate predictors of actual behavior of the target individual (Darley & Fazio, 1980, p. 870).

"The term stereotype refers to those interpersonal beliefs and expectancies that are both widely shared and generally invalid" (Miller & Turnbull, 1986, p. 233).

"The large literature on prejudice and stereotypes provided abundant evidence that people often see what they expect to see: they select evidence that confirms their stereotypes and ignore anomalies" (Jones, 1986, p. 42).

"In this section of the paper, we consider some representative findings to illustrate the powerful effect of social stereotypes on how we process, store, and use social information about group members" (Devine, 1995, p. 476)

None of these papers, despite many being published in some of the most influential outlets in academia (Science, Annual Review Chapters and the like) presented any evidence on the (in)accuracy of stereotypes, or that the effects of social stereotypes on anything are particularly powerful. Such data did not exist then and does not exist now. Of course, stereotypes do sometimes lead to biases, but they are usually quite modest. And they are indeed sometimes wildly inaccurate. But the existence of occasionally wildly inaccurate stereotypes does not justify declaring them inaccurate writ large. This is obvious in any other walk of life: no one would declare New Jersey to be a land of eternal winter based on a few cold weeks in January.

Then there is this:

In it, you will find this claim:

“If there is a kernel of truth underlying gender stereotypes, it is a tiny kernel, and does not account for the far-reaching inferences we often make about essential differences between men and women.”

Note the lack of a citation to anything. This is in context, not out of it. There are at least 11 published papers reporting 16 studies assessing the accuracy of gender stereotypes, typically finding moderate to high accuracy, and Ellemers neither discussed nor cited a single one.

Another set of my favorite data-free claims are shown here:

They presented no evidence regarding the first, second or third claims, and the fourth is absurd on its face.

Other data free claims one can find in the literature are that minorities face a “hostile obstacle course” in academia (citing a dataless Tweet and a paper reporting the interpretation of a Black woman’s dream as “evidence”); that self-fulfilling prophecies accumulate over time to exacerbate inequalities; and that the “traditional” meaning of diversity in legal contexts was restricted to demographics. Another is that standardized tests are “biased.” Woo et al (2023), addressing this issue, produced one of the greatest single lines in the psychology literature:

Criticizing the tests themselves as discriminatory and responsible for racial inequities in graduate-school (or college) admissions is much akin to “blaming a thermometer for global warming” (National Council on Measurement in Education, 2019)

So now we have evidence for everything in this heuristic equation:

%False Claims = (%Unreplicable Findings) + (%References to Unreplicable Findings as If They are True) + (%False Claims Based on Replicable Findings) + (%False Claims Based on Ignoring Contrary Evidence) + (%False Claims Due to Censorship) + (%False Claims Based on Making Shit Up Completely)

Unreplicable Findings is 50%. I do not have numbers for the other parts of this equation. I doubt all of the claims in the remaining 50% are wrong; and I am sure they are not all correct. So let’s split the difference and guesstimate that about half the remaining claims are wrong. This has the added benefit of minimizing the potential for error. If 49% of 50% remaining claims are wrong or if 49% of the 50% are right, 75% is off by 24%. But, say, if the guesstimate was 51% were wrong when, in fact, 99% are wrong, it would be off by 48% (just as if the guesstimate was 99% are wrong but only 51% are wrong).

75% is merely a guestimate, or, if you prefer, a data-informed hypothesis. But its fairly conservative. It estimates that each of these pieces of the equation occur in only single digits, percentage-wise. It assumes the successful replication rate is 50% when it is probably lower. But even using these conservative, or, if you prefer, benevolent estimates, when added to the half of findings that are unreplicable, we get

~75% of Psychology Claims are (Likely to be) False

I am not saying this rises to the level of scientific fact. I am saying its a reasonable first pass at a guesstimate. Maybe the real number of false claims is 63% or 84% or 91% or even only 55%. Whatever it is, even if it is 55%, one thing it is not is … good.

And that 75% figure is almost certainly closer to a scientific fact than … many claims that appear in the psychology academic literature.

Footnoes

If all you know is that a claim is published in some psychology outlet, you should dismiss it and move on until it is confirmed by independent researchers. Of course, sometimes, you know more than that a claim has been made. If you know that the claim has already been confirmed by highly powered, pre-registered studies, and skeptical meta-analyses including many tests for bias, you know a lot more than simply “the claim was published.” (see footnote 1 for brief explanations of power, pre-registration and skeptical meta-analysis). But if the study claims to discover something new or you are first coming across it, this essay will explain why you should simply not believe it until it is subsequently confirmed by independent researchers.

The spirit of this essay owes much to Ioannidis’s famous article:

However, although we reached similar conclusions, our approaches were quite different. Ioannidis’s conclusions are based primarily on the low statistical power of many studies and the assumption that, a priori, most hypotheses are likely to be false. I agree that these were reasonable assumptions, though if one makes different assumptions, one reaches a different conclusion. In contrast, in this essay, I start with an empirical fact (about half of all replication attempts in psychology fail) and then proceed by identifying specific additional ways claims can be false other than failed replications. My probability estimates are guesstimates, I know of no way to statistically model them, though if you do, zing me an email and just maybe, we can collaborate on such a project.

Scientists are bullshitting when they promote claims as true based on weak logic or data. They may believe their own bullshit, which merely means they have successfully bullshitted themselves.

For the statistically uninitiated, p<.05 can be thought of as the “statistical gatekeeper” of psychology. If some statistical analysis (comparison of means, correlations, regressions, etc.) reaches “p<.05” it is often called “statistically significant” and the researcher is liberated to take their results seriously and impose all sorts of deeply psychological interpretations on those results. If p>.05, the results are usually treated as if there is no there there and, typically, the research is not likely to see the light of day (with “light of day” being defined as “publication in a peer reviewed journal.”). There are some exceptions to this, but they are beyond the scope of this essay.

Registered replication reports are replication studies that have been accepted by journals before they were actually conducted. These are especially informative because they pretty much guarantee that the paper will be published regardless of whether the research succeeds or fails at replicating the prior research. This is in stark contrast to the convential peer reviewed psychology literature, which is only published after it is conducted — thereby permitting reviewers and editors to reject the paper if it fails to replicate — which was disturbingly common in psychology for most of my career.

Amusingly, we recently submitted as a registered replication report a series of studies that not only failed to replicate M-R, they were a reversal — using methods just about identical to theirs, we found biases against men.

Another great article. I can see why you use Gould's definition of a fact but it is still a bad definition and this is perhaps why you have often found yourself using scare quotes around the word ‘fact’. A fact is a way that the world IS, more technically, it is a state of affairs that obtains. States-of-affairs, and therefore facts, are not the kind of thing that can be confirmed or disconfirmed.

What can be confirmed are statements that state states-of-affairs. A statement stating a fact is a truth. Scientific statements are used to make claims about what the facts are and such claims can be the outcome of a body of scientific research. If that body of research is sufficiently comprehensive and methodologically sound many of its claims are scientifically justified statements and belief in them is justified. It is such scientifically justified statements that can be said to be ‘confirmed to such a degree that it would be perverse to withhold provisional assent’. Statements that state a fact can never turn out to be false but scientifically justified statements can turn out to be false.

Consequently, it is impossible for Gould’s definition to be good for two reasons. Gould's definition should instead be given as a definition of when a claim is a scientifically justified statement and when belief in that claim is scientifically justified. I would still reject it as a definition, though. Rather, his perverse-to-withhold-assent condition is a usefully short generally reliable indicator of a scientifically justified claim.

I get it but, as usual, this approach has a very strong subdisciplinary bias. In my area, cognitive psychology/cognitive neuroscience, I hardly know any (systematically) non-replicable findings. Stroop effect, Simon, flanker, memory effect, recency etc., learning, attentional blink, you name it. Some higher-order interactions may be context-dependent, but the basic effects (orignally obtained with dramatically small samples, sometimes just the two authors) are super solid. So most of this handwaving business may be restricted to effects and phenomena that are more penetrated by culture. That's not so surprising, but please don't over-generalize from your own (admittedly messy) field...