In this post, I summarize the working theory for one of our papers,1 which is more or less in press.2 Followup posts will present the results from two empirical studies of botification.

Botification

We used the term botification to refer to a process by which some people who use social media can become increasingly automated, performative, or manipulated by outrage and algorithms. Bots are automated programs designed to interact autonomously on social media platforms, mimicking human users. Bots are often used by bad actors to promote propaganda and sew discord. As a result, bots are often unleashed to shift online discourse away from sincere and open civic engagement and toward outrage, conflict, simplistic narratives, polarization, extremism, and authoritarian attitudes.3

Botification, therefore, refers to a process by which people’s social media interactions, and, we argue, their underlying psychology while using social media, become more bot-like. We proposed that botification represents a cognitive state in which individuals rely heavily on mental shortcuts and heuristic-driven behaviors, mirroring the reactive and automated processes of a computer program or algorithmic bots. This includes sometimes enthusiastically or even gleefully promoting the erosion of trust in civic and democratic practices and institutions.

To conceptualize the psychological and sociopolitical role of social media in (anti)democratic behavior, we introduce The Botification Model (Figure 1). This framework captures the recursive and mutually reinforcing dynamics through which digital platforms may disrupt trust, distort internal models of the self and society, and promote authoritarian tendencies. Each component of the loop not only leads to the next but amplifies the previous, creating a bot-like self-reinforcing system of cognitive, emotional, and civic decline.

According to the model, social media use immerses many people in a high-volume and often emotionally charged information environment. Importantly, the social media environment is not a neutral or organically emergent space. Platform content is structured by engagement-optimized algorithms. To maximize ad revenue, social media platforms often amplify and promote content that generates high levels of user engagement because such content tends to be more profitable – advertisers pay more for content that receives wider exposure. Because content high in emotional or moral content often drives engagement, algorithms are more likely to amplify these sorts of posts than well-reasoned, nuanced, balanced, data-filled posts.

Furthermore, the vast amounts of information available on social media can be conflicting and overwhelming, making it hard to identify what is true, real, or correct, leaving the user in a fragmented state of information overload – a condition in which individuals face more information than they can meaningfully process. We hypothesize that the rise in social media use, characterized by its rapid and fragmented dissemination of information, disrupts individuals’ ability to make coherent sense of their social and political environments. These platforms often flood users with emotionally charged, conflicting, or misleading content. The model proposes that this creates uncertainty not just about the world, but also about one’s own place within it.

Individuals must be able to maintain a working mental model of themselves (self model in Figure 1) and their environment (world model in Figure 1) in order to make informed decisions, act with intention, and remain psychologically stable. This kind of self-understanding requires a basic, coherent sense of “who I am,” “what I believe,” and “how I relate to others.” A breakdown of this system can lead to psychological distress, which is marked by heightened uncertainty, anxiety, and a perceived loss of control.

According to the Figure 1 Botification Model, information overload, especially by the type of propaganda and simplistic and emotionally-charged content common on social media, can create distorted world and self models that set the stage for the disruption of trust in civic and democratic norms and institutions. In a context of high uncertainty and perceived lower personal control, individuals are more likely to embrace authoritarian order, which is characterized by simplistic thinking, polarization, demonization, and willingness to punish perceived enemies. These dispositions and beliefs may offer a temporary illusion of clarity and control, but in reality, they reinforce distress and deepen distrust.

As individuals return to social media to resolve their confusion or validate their views, the cycle begins anew. This return can be passive or active. By passive we mean viewing others’ posts without actively engaging with them. But users may also actively engage on the platform to amplify their own views, not only as a means of making sense of their experiences but also to seek validation, perform identity, and garner social reinforcement. By sharing emotionally resonant or ideologically charged content shaped by distorted worldviews, bot networks, and authoritarian narratives, users participate in the recursive amplification of the types of beliefs and anxieties that can not only intensify their own distress, but erode trust in civic and democratic practices and principles.

Also note that the title refers exclusively to Americans. That is because we know far more about what is going on here than we do about, say, Germany, Nigeria, or Indonesia. I definitely do not think Americans are uniquely bad (quite the contrary) or vulnerable to these sorts of forces. It is distinctly possible that similar processes occur internationally, but we have neither the experience nor the data to address that. It is of course also possible that nothing at all like this happens elsewhere.

Some Real World Examples?

The theory here is new, and, except for the studies to be described in my next two posts, there are no hard, empirical studies supporting it. In speculation, then, I suggest the following may well have reflected botification at least in part:

Cancel culture, which has often taken the form of mobs forming using social media to advance oversimplified narratives in the service of demonizing, denouncing, and punishing someone

The society-wide moral panic over racism after the killing of one Black man by one psychopathic cop.

My personal favorite, the entire saga of Fiedler on the Roof and the Nonexistent Racist Mule, which was initiated by an academic social media mob.

Delusions of Israeli “genocide.”

The brief moral panic over supposed Haitian pet-eating.

The online support for and even glorification of Luigi Mangione, who has been arrested for the murder of the CEO of United Health Care and is awaiting trial.

Of course, moral panics, propaganda, and denunciations existed long before social media, so clearly social media is not the sole cause or facilitator of these sorts of phenomena. The botification hypothesis is that, for at least some people, social media exacerbates this nasty stuff, thereby exacerbating whatever the ambient tendencies were for these sorts of things to occur anyway.

What’s Next?

Parts II and III of this series on botification will present the first two studies, respectively, providing initial empirical tests of predictions derived from the model of botification. Study I is on the role of social media use in producing civic disalignment, professions of support for democracy in the abstract (e.g., agreement that public officials should be elected by majority vote) which are readily discarded by some if the “wrong” type of person gets elected. Study II is on the role of social media use in permission structures for political violence, i.e., glorification and encouragement of political violence online, sometimes in the name of “protecting” democracy from “fascists.” The botification hypothesis in both cases is that social media use is associated with greater willingness to throw democracy out the window if one despises/opposes the winners or even the agendas of particular groups; and that social media use is associated with more support for political violence.

The ideas here are still in development, and critical evaluations (which include both positive and negative comments) are welcome. However, please keep it substantive. “This is an absurd model and you’re an f’ing idiot” will get deleted. “Its good as far as it goes, but how is it falsifiable?” would be a completely reasonable comment and not get deleted.

I’ll help get you started. The Botification Model has a lot of arrows heading in one direction. Conventionally, those mean “causality flows in this direction but not in the reverse direction.” Although I presented the model as it appears in the paper, I think all the arrows should be double-headed, which means causality could flow in either direction (pending research that clearly falsifies any particular direction). I will advocate to my co-authors for this change in a revision, but, because I have not done so yet (not counting that some will see this essay), I have no idea how they will respond. Because it is a co-authored paper, I cannot dictate terms, and am willing to compromise sometimes, even when I disagree. Or, perhaps, they will persuade me that the one-sided arrows are correct. You never know.

There is another problem, or, at least, limitation with the theory. It does not even attempt to explain why only some people become botified. Plenty of people use social media without becoming simple-minded conspiracy theorists and authoritarians (I think). So, why some people but not others? No clue (yet, but we will work on it).

Commenting

Before commenting, please review my commenting guidelines. They will prevent your comments from being deleted. Here are the core ideas:

Don’t attack or insult the author or other commenters.

Stay relevant to the post.

Keep it short.

Do not dominate a comment thread.

Do not mindread, its a loser’s game.

Don’t tell me how to run Unsafe Science or what to post. (Guest essays are welcome and inquiries about doing one should be submitted by email).

Footnotes

“… one of our papers…” Digital, in the subtitle, “Digital erosion of Civic Norms,” refers to social media use. “Civic norms” refer to principles and practices of liberal democracy.

“More or less in press”? Joe Forgas has been running small, thematic social psychology conferences since the 1990s. The format is this: 1. Draft a paper; 2. Present the work as a talk at his conference; 3. Revise based on the other presentations and comments from a reviewer or two who reads the paper. Every conference so far has produced a published edited book of these chapters. This essay is based on the theory component of a talk based on the paper that I will presenting at his conference in July, 2025. Forgas has our draft. So it is “more or less in press” though it will surely be revised before it actually gets published. It takes place in Visegrad, Hungary, which is the home of a medieval castle built to defend against the Mongols that is currently being restored. Little did you know that, in an earlier life, I was made King of Hungary for having successfully defended it against The Golden Horde.

This is an artist’s recreation of what it originally looked like. The castle on top (defensible motte, “mountain”) is a museum in various states of decay and restoration; you can see the ruins of the long wall from the motte to the bailey (the lower portion), and the tower overlooking the bailey is also a visit-able museum. BUT the delicious thing is: It’s a real life motte & bailey!

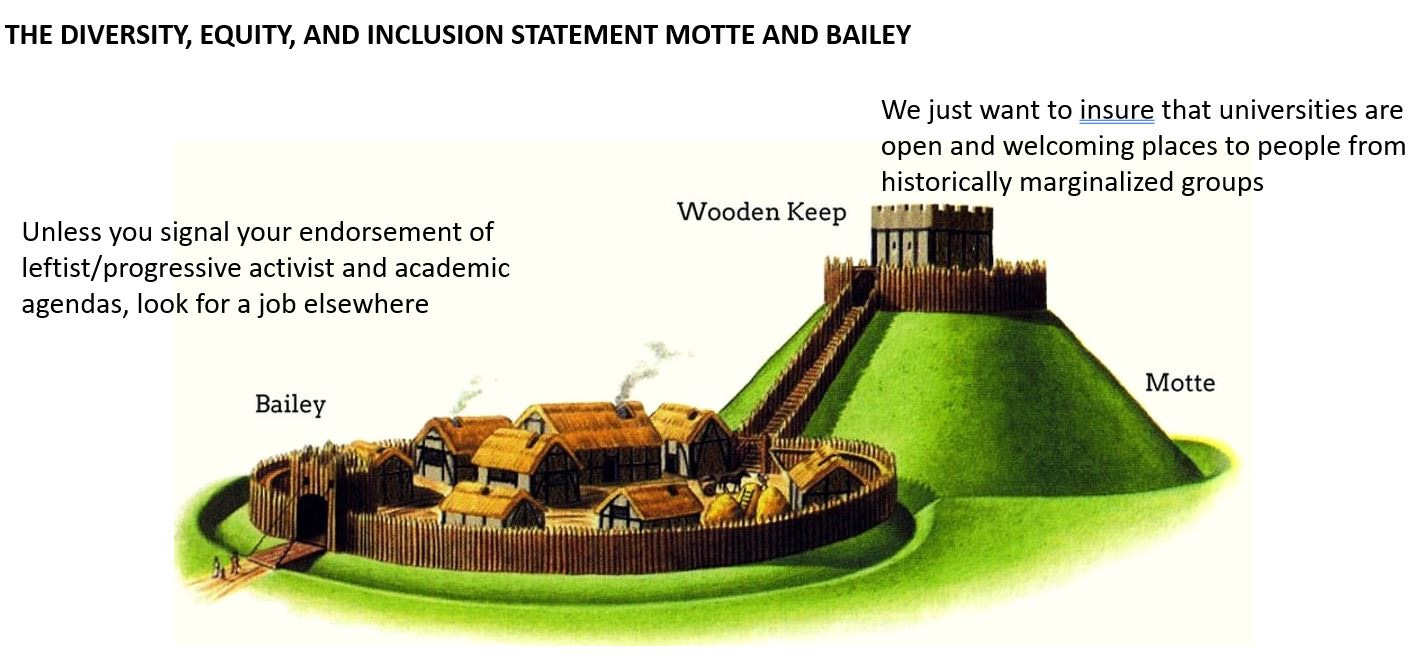

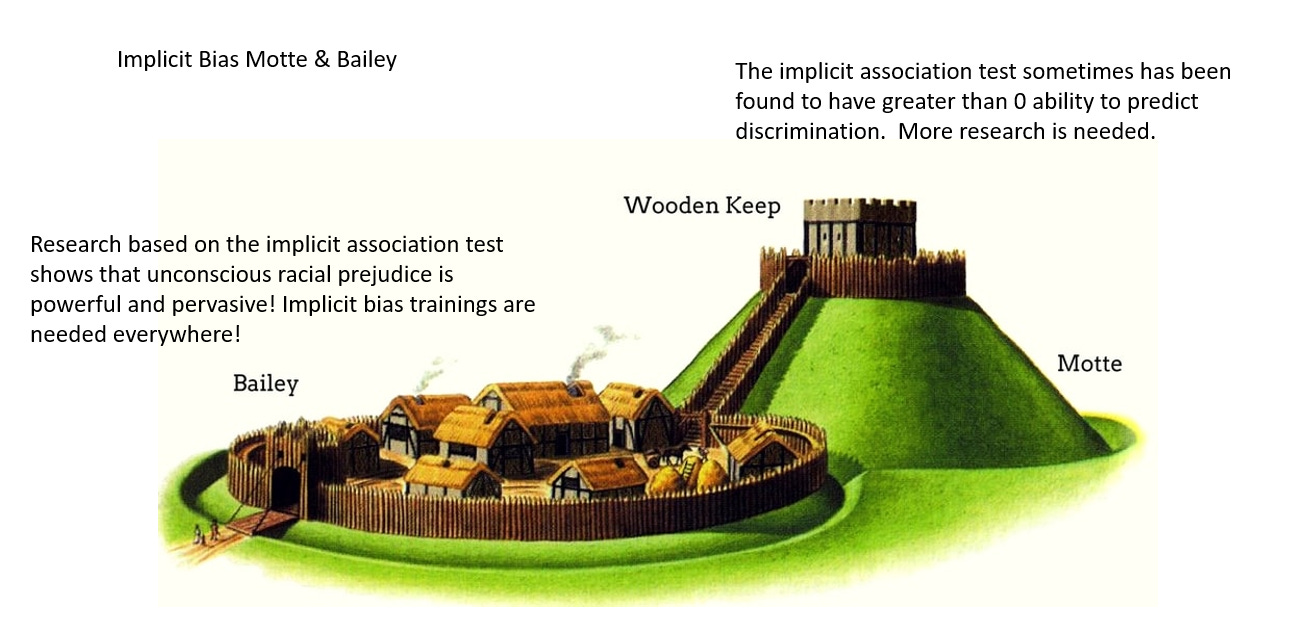

Now, if you do not know what a motte & bailey is in rhetoric, I will just say two things and provide some examples (it warrants an essay for another day). Early in my career motte&bailey type arguments were all over social psychology as pushback against my attempts to rein in its worst excesses, but I did not understand what was going on and kept getting befuddled by them. Once I understood that rhetorical motte & baileys were tricks designed to socially defend logically or empirically indefensible positions, lord above, it all made sense. Some rhetorical motte & baileys:

“…bots are often unleashed…” The paper is meticulously referenced. But because this is an essay, I have deleted references for readability and because most people could not care less about them. If you want the paper, ping me, and I will send you the submitted version.

Yes!

I've been calling all the AWFLs I know "NPR totebags" as they all have the exact same beliefs and ideas spoken in the same exact jargon, all of it formed and processed by the algorithms which have replaced their brains.

But BOTS is much better, much more catholic and comprehensive.

BOTS! it is

Thanks and all praise to Lee Jussim.

I have a theory about why some people become botified: that feeling of overwhelm when the social media onslaught prevents someone from making sense of the world is scary, destabilizing and depressing. It is far more comfortable to join a team and allow that team's ideology to frame/explain the world than it is to live in the discomfort, do more research and discuss the topics with others. Many many many of my west coast friends and family are apparently incapable of doing that work.