This post is in three sections:

The Manhattan Institute, in an effort led by conservative activist and would-be reformer of academia, Chris Rufo, has issued a statement calling for … the reform of academia. Chris asked me (and several others) to sign on. I did.

I explain why, despite some reservations, I signed on.

The statement has received some vehement criticisms. I explain why I think some of their arguments are wrong, some are implausible nightmare fantasies, and, even when they make good arguments, fail to make a strong case for why the Manhattan Institute proposals are worse than the status quo.

If you have already read the Manhattan Institute Statement, you can skip to the next section, titled My Commentary.

I. The Manhattan Institute Statement on Higher Education

America’s colleges and universities have long been the bright lights of our civilization. For nearly four centuries, they have pioneered new fields of knowledge, brought the arts and sciences to new heights, and educated the men who built our republic. But over the past half-century, these institutions gradually discarded their founding principles and burned down their accumulated prestige, all in pursuit of ideologies that corrupt knowledge and point the nation toward nihilism.

There have been warnings. From William F. Buckley’s God and Man at Yale to Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind, conservatives pleaded for the universities to maintain their basic commitments, while liberals promised to reform the campus from within. All of these attempts failed. The conservatives were ignored; the liberals were steamrolled; and the process of ideological capture accelerated.

Now, the truth is undeniable. Beginning with the George Floyd riots and culminating in the celebration of the Hamas terror campaign, the institutions of higher education finally ripped off the mask and revealed their animating spirit: racialism, ideology, chaos. The current state of affairs is untenable. The American people send billions to the universities and are repaid with contempt. The leaders of these institutions seem to have forgotten that the university and the state are bound together by compact. During the Founding era, schools of higher education were established by government charter and written into the law, which stipulated that, in exchange for public support, they had a duty to advance the public good and, if they were to stray from that mission, the people retained the right to intervene.

Over the years, the locus of this particular compact has changed—the universities have entered into a relationship with the federal government—but the underlying principle remains the same: Higher education must serve the public good and, in times of trouble, must be reformed. The troubles of the current era are neither light nor transient. The universities have brazenly, deliberately, and repeatedly violated their compact with the American people. They have engaged in a long train of abuses, evasions, and usurpations which, with every turn of the ratchet, have moved our society toward a new kind of tyranny—one in which ideology determines truth, and the university functions as a political agent of the left.

Let us enumerate the facts:

• The universities have capitulated to the radical left’s “long march through the institutions,” which has converted them into laboratories of ideology, rather than institutions oriented toward truth.

• The universities have violated their commitment to serve in a position above day-to-day politics and, instead, have adopted a narrow political agenda and engaged directly in partisan activism, with particularly disastrous results for the humanities and social sciences.

• The universities have built enormous “diversity, equity, and inclusion” bureaucracies that discriminate on the basis of race and violate the fundamental principle of equality—that high prize which was inscribed in the Declaration of Independence and codified into law with the Fourteenth Amendment and the Civil Rights Act.

• The universities have contributed to a new kind of tyranny, with publicly funded initiatives designed to advance the cause of digital censorship, public health lockdowns, child sex-trait modification, race-based redistribution, and other infringements on America’s long-standing rights and liberties.

• The universities have corrupted faculty hiring practices with racial quotas, ideological filters, and diversity statements, which function as loyalty oaths to the left and have virtually eliminated conservative scholars from the prestige institutions.

• The universities have degraded the liberal arts with reductive ideologies that no longer aim to preserve and discover what is highest in man, but to unleash resentments against Western civilization, from the Greeks and Romans to the English and the Americans.

• The universities have ceased to represent the nation as a whole; rather, they have divided Americans into “oppressor” and “oppressed,” and have, in effect, declared war on millions of Americans who simply want to live, work, worship, and raise families in peace.

Enough. The American people provide status, privileges, and more than $150 billion per year to the universities. In light of these transgressions, we have every right to renegotiate the terms of the compact with the universities and to demand that they return to their original mission: to pursue knowledge, to educate the citizen, and to uphold the law. In exchange for continued public support, these institutions must abide by the principles of the Constitution and honor their obligation to public good.

To that end, we call on the President of the United States to draft a new contract with the universities, which should be written into every grant, payment, loan, eligibility, and accreditation, and punishable by revocation of all public benefit:

• The universities must advance truth over ideology, with rigorous standards of academic conduct, controls for academic fraud, and merit-based decision-making throughout the enterprise.

• The universities must cease their direct participation in social and political activism; the proper vehicle for criticism is through the individual scholar and student, not the university as a corporate body.

• The universities must adhere to the principle of color-blind equality, by abolishing DEI bureaucracies, disbanding racially segregated programs, and terminating race-based discrimination in admissions, hiring, promotions, and contracting.

• The universities must adhere to the principle of freedom of speech, not only in theory, but in practice; they must provide a forum for a wider range of debate and protect faculty and students who dissent from the ruling consensus.

• The universities must uphold the highest standard of civil discourse, with swift and significant penalties, including suspension and expulsion, for anyone who would disrupt speakers, vandalize property, occupy buildings, call for violence, or interrupt the operations of the university.

• The universities must provide transparency about their operations and, at the end of each year, publish complete data on race, admissions, and class rank; employment and financial returns by major; and campus attitudes on ideology, free speech, and civil discourse.

We acknowledge that the crisis of higher education will not be resolved in an instant. Still, we maintain faith that these proposed reforms will provide a starting point for a broader restoration, which can push back the forces of radicalism and create the space for real knowledge. Despite the challenges, we refuse to abandon the hope that America’s universities can once again be those bright lights, pursuing truth, sustaining our highest traditions, and educating the future guardians of our republic.

Christopher Rufo, Manhattan Institute

Jordan Peterson, University of Toronto

Bishop Robert Barron, Diocese of Winona-Rochester

Virginia Foxx, United States Congress

Victor Davis Hanson, Hoover Institution

Niall Ferguson, Hoover Institution

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Hoover Institution

Sergiu Klainerman, Princeton University

Omar Sultan Haque, Harvard University

Joshua Rauh, Stanford University

John Cochrane, Stanford University

Iván Marinovic, Stanford University

Dorian Abbot, University of Chicago

Joshua Mitchell, Georgetown University

Carol Swain, Vanderbilt University

Bradley Thompson, Clemson University

Gad Saad, Concordia University

Lee Jussim, Rutgers University

Eric Kaufmann, University of Buckingham

J.D. Haltigan, University of Buckingham

Alex Priou, University of Austin

Peter Boghossian, University of Austin

Pavlos Papadopoulos, Wyoming Catholic College

Pedro Domingos, University of Washington

Dan Bonevac, University of Texas

Luciano de Castro, University of Iowa

Brandon Warmke, University of Florida

Bryan Caplan, George Mason University

Adam Kolasinski, Texas A&M University

Joshua Katz, American Enterprise Institute

Christina Hoff-Sommers, American Enterprise Institute

Solveig Gold, American Council of Trustees and Alumni

Jay Greene, Heritage Foundation

Scott Yenor, Claremont Institute

Jim Piereson, Manhattan Institute

Peter Wood, National Association of Scholars

Yoram Hazony, Edmund Burke Foundation

Ben Shapiro, Daily Wire

Rich Lowry, National Review

Roger Kimball, The New Criterion

Daniel McCarthy, Modern Age

Mark Bauerlein, First Things

David Rieff, Author

My Commentary

This is a call to political action, not a scientific treatise, even though it sometimes makes fact-claims.1 As such, I have different standards for signing my name to something like this than I would for a scientific paper.

Science is usually about some version of discovering or figuring out things that are actually true. Political activism is about changing something (the world, the nation, the locality, even one’s workplace).

The Manhattan Institute Statement is a call to reform. I did not sign on because I agree with every statement it makes, which I do not. I signed on because I endorse the proposed reforms, either entirely or with some modifications (and they are sufficiently nonspecific that exactly how they would actually be implemented is wide open).

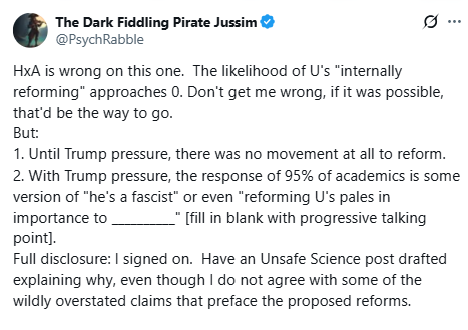

I also signed on because I have seen no evidence that academia will reform itself to address the problems resulting from its overt politicization and evolution into an engine for the advancement of progressive values, policies, and worldviews. Before Trump, calls to reform were made by an infinitesimal proportion of faculty, who were not merely duly ignored, they were often denounced (such as here or here), and the radicalization of the faculty simply continued apace, and bringing with it, a cratering of support for academia especially among Republicans but even to a lesser extent among Democrats.

Since Trump’s attempts to reform/assaults on academia, there has been far more open discussion of the need to reform academia and how to do it. This is good but, so far, entirely ineffective at actually getting universities to change much.2 Except when the Trumpian assault has been massive, as it has been in the case of Harvard and Columbia, I have seen literally no serious efforts by most universities to attempt serious reform.

Don’t get me wrong. In my Academic Utopia, universities would chart their own reform courses. Administrators might enlist reform-minded faculty at their institutions, and, perhaps, scholars outside the institution who have been advocating for reform as consultants, and begin mapping out, and implementing, changes.

But I’ve seen no evidence that anything like this is happening. There is absolutely no reason to believe American universities were going to embrace anything remotely resembling the reforms described in the Manhattan Institute Statement without unnecessarily draconian and ham-handed policies – strongly suggesting that “unnecessarily” may be misplaced there.

Speaking not from data (I do not have 8 surveys of faculty on hand on this) but from extensive personal experience, most faculty continue to respond to Trump’s policies towards academia with glib dismissals of Trump’s “fascism,” why “now is not the time to discuss internal problems, which pale in comparison to Trump’s Evil,” and with nearly complete disinterest in or outright hostility to attempting to integrate Republicans and conservatives into academia in ways that might solve many of academia’s worst political problems and many of their scientific ones (at least on politicized topics) to boot.

I Do Not Agree with Everything in the Manhattan Institute Statement and That’s OK

Some of the rhetoric in the statement strikes me as a bit histrionic. I am not going through it line-by-line but here is one example:

the institutions of higher education finally ripped off the mask and revealed their animating spirit: racialism, ideology, chaos.

Chaos is rare. I suspect that “racialism” refers mostly to DEI, and lord knows it was everywhere, and so is leftist ideology. But “animating spirit”? Maybe for a minority but not most academics I know. Just as racial discrimination can occur without the U.S. being a white supremacist society, ideological biases can exist within academia without being some sort of prime directive or “animating spirit.” There are other statements I do not really buy, but: 1. You get the point; 2. What matters far more than the background here are the specific calls to reform.

Put differently, even if the background was entirely loony-bin worthy, if I thought the calls for reform were worthy, I’d still support it.

I think most of the reforms it calls for are necessary and justified and all of the reforms it calls for would be valuable, albeit in potentially modified form. Again, I will give just one example.

The universities must cease their direct participation in social and political activism; the proper vehicle for criticism is through the individual scholar and student, not the university as a corporate body.

I mostly agree with this; it is essentially a call for universities to adopt institutional neutrality. However, the Kalven Report, which established institutional neutrality as guiding principle for University of Chicago, included exceptions for policies that directly affect the university. For example, policies governing indirect costs on grants or the deportation of foreign students enrolled in the university. The Manhattan Institute Statement includes no such exceptions, and it should.

I have similar quibbles with many of the proposed reforms. However, the Manhattan Statement is not a detailed policy plan with all details worked out. It is a call to action. And I am definitely on board with most of the actions it calls for, even while recognizing that the Devil is always in the details.

Timid handwringing, sincere desires not to alienate leftist academics, and outright fear of the consequences that could come from aggressively opposing the left/far left takeover of many universities have, to date, done nothing to reform academia. The Manhattan Institute Statement calls for some strong medicine, and some of it tastes pretty bad. But the patient is pretty ill and all the signs are that the illness has progressed for a very long time with no sign of reversal. My judgment is that it is time for that strong medicine.

I am pragmatic enough that, long ago, I made my peace with not allowing the perfect be the enemy of the good – especially when one is seeking political change. The Manhattan Institute Statement is like a good roadmap (to reform): It offers considerable promise for improving American universities, even if every turn, difficult intersection, and pothole is not fully captured on that map AND even if using that map comes with some risk of making a bad wrong turn. There is no evidence that Einstein actually said this, but it’s a good point nonetheless:

A Note on Cooties or How Middle School Never Ends

Bear with me here. This seems like a completely different topic than The Manhattan Institute Statement, but its not.

You don’t want to be the kid with cooties. The kid with cooties is tainted, unclean. And the best way to avoid getting cooties is to never ever be seen with any kid that has cooties. Cooties is the “ostracism” game. It can be played in genuine fun, a lot like tag, but kids also play it half-jokingly, where its “fun” to ostracize the “right” kid, deemed off or an outsider in some way.

And you thought this was just a stupid kids’ game. Nope. Its also played by academics, in the form of open letters or social media campaigns that seek to ostracize someone, typically with some sort of moral uncleanliness.

That is what happened to Alex Byrne, the MIT philosopher who worked on the CDC report highly critical of gender affirming care. He was denounced by hundreds of people, mostly graduate students, in an open letter, not for getting anything wrong in the report, but for working with the Trump Administration. Trump is Evil Incarnate so anyone working with anyone in the Trump administration is morally unclean. From the open letter:

Collaboration with the Current Presidential Administration. The past few months have witnessed the Trump administration engage in the kidnapping of international graduate students from the streets, the deportation of innocent people to dangerous foreign prisons without due process, the cutting of lifesaving aid to millions across the world, and the undermining of the independence of colleges and universities across the country. We find these actions appalling, unethical, and undemocratic.

For these reasons, we believe it is deeply myopic for any academic to collaborate with the Trump administration in this moment, regardless of one’s particular views about gender. However misguided one may think “gender ideology” is, it is simply unconscionable to for that reason, make common cause with an administration so engaged.

The open letter has received some pushback (e.g., by Byrne himself ), but my favorite is this:

In it, among other things, you will find this:

(2) Collaboration causes cooties

Next, the open letter details a number of respects in which the Trump administration is (truly and deeply) appalling. But they then add:

We believe it is deeply myopic for any academic to collaborate with the Trump administration in this moment… it is simply unconscionable to… make common cause with an administration so engaged.

This also seems clearly false. Suppose that, while DOGE was eviscerating USAID, they had asked (say) Peter Singer to help them prioritize which programs to cut. And suppose that, by collaborating with this process, Singer could have convinced them to preserve PEPFAR (far and away the most important and effective USAID program). This would have saved perhaps half a million lives (assuming the funding is not otherwise restored). Not all policies are as high-stakes as that one. But government policies are a big deal. It’s just crazy to suggest that academics shouldn’t try to improve the policies of the United States government because they’d catch cooties from sharing documents with Trumpists.

When does it make sense to boycott policy-making?

In general, I think we should have a strong default prior that it’s good for academics to try to improve public policy. The stakes are high, and academics have distinctive expertise that (we may hope) make their efforts more likely to do good than harm. That doesn’t change just because the government is evil.

Of course, we should be trying to make the policies morally better, which may diverge from the goals of the administration. One shouldn’t collaborate towards evil ends, such that one’s contribution makes things even worse than they’d otherwise be. But the open letter doesn’t argue that Byrne has done any such thing. (That would require arguing against the substance of the report he helped produce,1 and furthermore arguing that the team would have produced a better report without his input. The latter seems especially implausible, given what we know of the Trump administration’s ideological commitments.) They just seem to be making an argument from cooties.

Now, there’s one context in which having academics boycott the government makes sense, and that’s if their taking such a staunch collective oppositional stance would (somehow) achieve more good, such as by forcing the government to reform in salutary ways. But academics have no such power over the U.S. government, especially one whose power base is as hostile to academia as Trump’s is. If anything, taking such a partisan professional stand, qua academics collectively, just seems likely to make things worse. I can’t imagine what concrete benefit the objectors anticipate resulting from their proposed intellectual boycott. (I suspect they’re sacrificing individuals for symbolism again.)

It is possible that those of us who signed the Manhattan Institute Statement will be similarly denounced. If so, I say go for it. It’s been working for me.

My Vita of Denunciation

This essay is dedicated to my many denouncers, some of whom are listed here.

But even if this effort by Rufo evokes no denunciation, all of us signing this letter are likely to be viewed by many academics as having cooties. However, I am pretty sure that most of those likely to view me that way already do so. Having survived middle school, I am pretty sure this will work out well. Or, as Jeff Mach puts it:

If as a culture you thrust people out, you run the risk of those people realizing they like it better on the outside

Bad, Bombastic, and Bankrupt Arguments Against the Manhattan Institute Statement

Inside Higher Education Article

This article recently appeared in Inside Higher Education:

It is written by John K. Wilson, who I had never heard of, so I looked him up. Both his X feed and other writing is filled with leftwing talking points, many of which are clearly clueless (with some exceptions). In 1995, he published this book:

It promotes the idea that PC is a myth concocted by malicious conservatives. I am not going to debunk the whole thing, but he has a whole chapter devoted to “The Myth of Reverse Discrimination.” Reverse discrimination refers to discrimination against White people, men, etc. His bombastic style is nicely captured in the paragraph that opens the chapter:

The backlash against affirmative action programs has produced an increasingly popular rhetoric of "reverse discrimination" that depicts the white male as the helpless victim of affirmative action, shut out of academic jobs and denied educational opportunities while "unqualified" minorities fill the university halls.

They may exist, but I know of precious few serious critiques of political correctness that depict white males as “helpless victims” or completely shut out of academic jobs (of course, he merely implied “completely” but did not say so). Reverse discrimination need not be so absolute as to shut people out completely. And we now know that, in fact, White (and Asian) applicants were indeed massively discriminated against in college admissions at least at Harvard and University of North Carolina. If John would like to place a bet on whether Black students had similar 100-200 point SAT advantages at other elite universities, I’d be glad to oblige.

This was not merely “reverse” discrimination, though it surely was that. It was also some of the best evidence of systemic racism in academia post 1970 ever produced. Systemic racism means racism by law, or by organizational or institutional policy. Even in the earlier Bakke and Grutter decisions that permitted “diversity” to be used in admissions:

They required admissions based on merit

They banned discrimination to achieve “social justice.”

I won’t go into all the details here because I presented them at length — including long excerpts from civil rights law, and both the Bakke and Grutter decisions here:

That’s race. What about “reverse discrimination” against males? Funny you should ask:

And of course, putting the lie to the rhetoric about evil conservatives ratcheting up a delusional moral panic over PC, academics from across the political spectrum (including many firmly on the left, such as Alan Sokal, Alice Dreger, Steven Pinker, Musa al-Gharbi, Alice Eagly, Yoel Inbar, and many many many more) have been warning about the leftist/progressive political corruption of academia for decades:

So not only did John get the whole “myth of pc” completely wrong, he got it bombastically wrong.

Enough about John’s prior work. Let’s consider his recent essay on the Manhattan Institute Statement.

Something that caught my eye last week was news of a statement calling for even more government control over higher education from a group of conservatives.

and later:

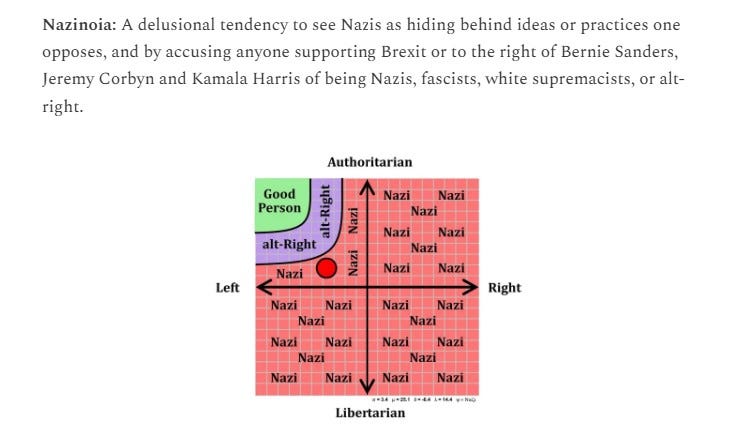

The nearly 50 signers of the Manhattan Statement represent a broad range of the alt right and the old right,

How does he know the signatories’ politics? I’d bet dollars to donuts that I know their politics far better than he does, and I only know the politics of maybe 11. Of those 11, four are definitely not conservatives for any conventional meaning of “conservative” (self-description, policy preference, voting, party membership), including me. And “alt right?” Shoot me now. At least he did not call us Nazis.

This presumption strikes me as of a piece with his bombastic and erroneous claims about the “myth of political correctness.”

It then goes downhill from there.

The Manhattan Statement is a recipe for tyranny. Even if some people might agree with its goals, what’s important are not the ends but the repressive means used to achieve them. It calls for “a new contract with the universities, which should be written into every grant, payment, loan, eligibility, and accreditation, and punishable by revocation of all public benefit.” We’ve already seen how the Trump regime has terribly, illicitly abused its power over government contracts to punish colleges without due process.

Heh. “Tyranny.” Last I looked SCOTUS has not overturned any of Trump’s actions vis a vis academia. If I am wrong about this, please place a link to such a decision in the comments. Rutgers President Holloway interviewed an eminent constitutional law scholar and the thematic point was simple and clearly stated:

Holloway, a scholar of American history, and Rosen, considered one of the country’s preeminent nonpartisan constitutional experts, addressed the topic, “What is a constitutional crisis and are we in one?’’

Rosen defined a constitutional crisis as: “The president ignoring an unambiguous order of the U.S. Supreme Court.”

“So, by this broadly accepted definition of liberal and conservative historians,” he said, “the answer is no. We are not yet in a constitutional crisis. Because the president hasn't defied an explicit order of the U.S. Supreme Court.”

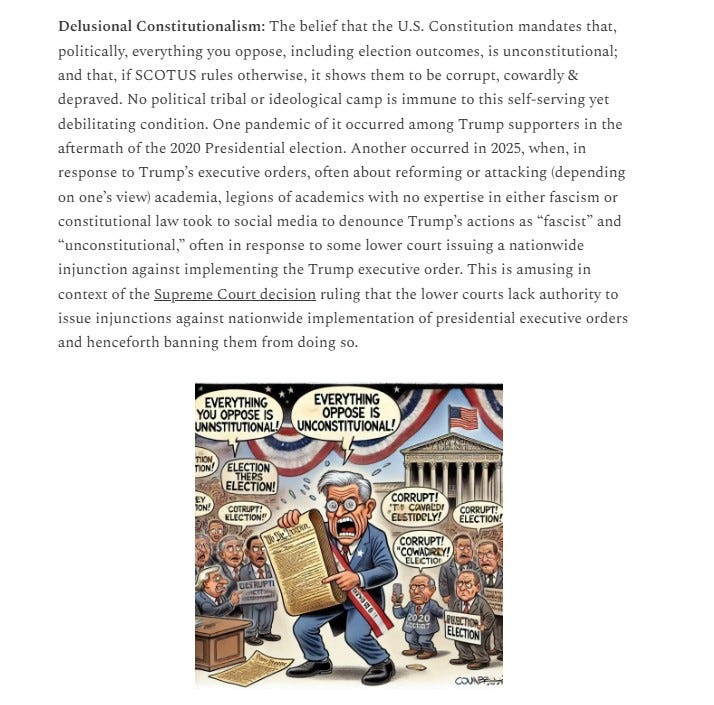

Rule of law is kinda the opposite of tyranny, even when you don’t like the policies being instituted. From The Orwelexicon:

And then there is this:

The Manhattan Statement would vastly expand this power to include all federal funding and student loans, making every college held hostage for its existence to any demands of the government.

This is silly on two grounds:

colleges are not required to accept federal money; nor are they entitled to it.

if colleges do take federal money, the federal govt, i.e., the elected representatives of the American people, have every right to make policies governing how that money can and cannot be used.

There is more, including some points in John’s essay that I agree with, but this essay is not about evaluating every last point, so let’s move on.

Heterodox Academy Weighs In

John Tomasi, who heads Heterodox Academy, weighed in with this post, which starts off well enough:

The Manhattan Institute statement’s recommendations for university reform are not novel; in fact, they are similar to a number of the reforms HxA recommended last month in our Open Inquiry U Reform Agenda.

Great. So we mostly agree on the goals. But then it goes on with what is presented as differences it has with the Manhattan Institute Statement:

Heterodox Academy is not calling for federal action to reform our universities. For nearly a decade, HxA has been a voice chiefly for internal reform … We are a membership organization that works collaboratively with our members — academic insiders — to improve our universities from within.

Heterodox Academy is not necessarily seeking a “politically balanced” university.

Heterodox Academy does not agree with the diagnosis the Manhattan Institute communicates.

It will be easier to take these in reverse order. The “diagnosis” of the Manhattan Institute statement is indeed a bit over the top, as I pointed out in my discussion above (e.g., about “chaos”).

Heterodox Academy is not seeking a politically balanced university. Fortunately, nothing in the Manhattan Institute Statement calls for it.

My biggest point of disagreement is, therefore, with the first point, that the academy should be reformed from within. I mean, I agree that it should be but I see no evidence that it will be. Here is why:

Commenting

Before commenting, please review my commenting guidelines. They will prevent your comments from being deleted. Here are the core ideas:

Don’t attack or insult the author or other commenters.

Stay relevant to the post.

Keep it short.

Do not dominate a comment thread.

Do not mindread, its a loser’s game.

Don’t tell me how to run Unsafe Science or what to post. (Guest essays are welcome and inquiries about doing one should be submitted by email).

Footnotes

On facts. I never saw much of a distinction with respect to epistemic status between scientifically-discovered facts, such as “ulcers are caused by bacteria” and obvious facts (the Sun rises in the morning), facts reported by news media (“Trump wins the 2024 Presidential Election”), and pretty much any other type of fact (“my cat will often try to run out the door if you are not careful.”).

Academic discussion of reform has not changed much. One exception is that over 100 institutions have adopted institutional neutrality — a commitment to avoiding commenting on the political issues of the day except when they directly affect the institution. I endorse institutional neutrality, so I think this is a good thing, but there is no evidence to believe it accomplishes very much. It does nothing to reform the array of dysfunctions that stem from the nasty combination of an insanely high proportion of radical and dogmatic faculty, and administrators who are either cowards or also true believers in imbuing the university with progressive (or more extreme) values.

As a former professor, I also signed the Manhattan Institute Statement, even though I do not agree with every sentence in it. Our university system needs a major overhaul, and it is very clear that the initiative to do so will not come from within the university system itself. And particularly for the state university system, state legislators are going to have to play a major role.

I wasn't asked to sign, and I probably wouldn't have signed, though that's mainly because I'm pretty allergic to signing petitions in general. A friend of mine once said his mantra was "I only sign petitions that I would sign if I were the only signatory." I like that and I've taken that to heart.

That said, I largely agree with your analysis here. The Manhattan preamble is very hyperbolic and somewhat off-putting, opening itself up to criticism by "laying out the facts" and then presenting non-empirical maximalist vagueries. But, Manhattan's specific calls to action are pretty much the Chicago Trifecta, enforced by the government, which I think is reasonable and I have publicly called for before: https://www.konstantinkisin.com/cp/152812681. Like you said, it's notable that HxA pointed out how similar their reform agenda was to the Manhattan statement after criticizing it.

It's also notable that the HxA statement's two main departures from Manhattan are: (i) being against government oversight, and (ii) not even mentioning the flagrant violations of federal laws (civil rights and others) that are a huge part of the problem on campus, and the feds' *pre-Trump statutory requirement* to step in and stop that. You are also right that HxA needs a better answer to the "why has almost no internal reform happened without government pressure?" question, if they're going to oppose all government oversight. It'd even be fine for them to say, "we, HxA, choose to focus on internal reform as our role, and we don't want to get involved in government oversight". But if they're going to say "government oversight is bad", they need a much more credible theory of change to offer as an alternative.