Why Accuracy Dominates Bias and Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

I recently discovered a terrific thread on X summarizing my 2012 book.1

It is by Dan Hopper, who can be found on X here.

Without any further ado…

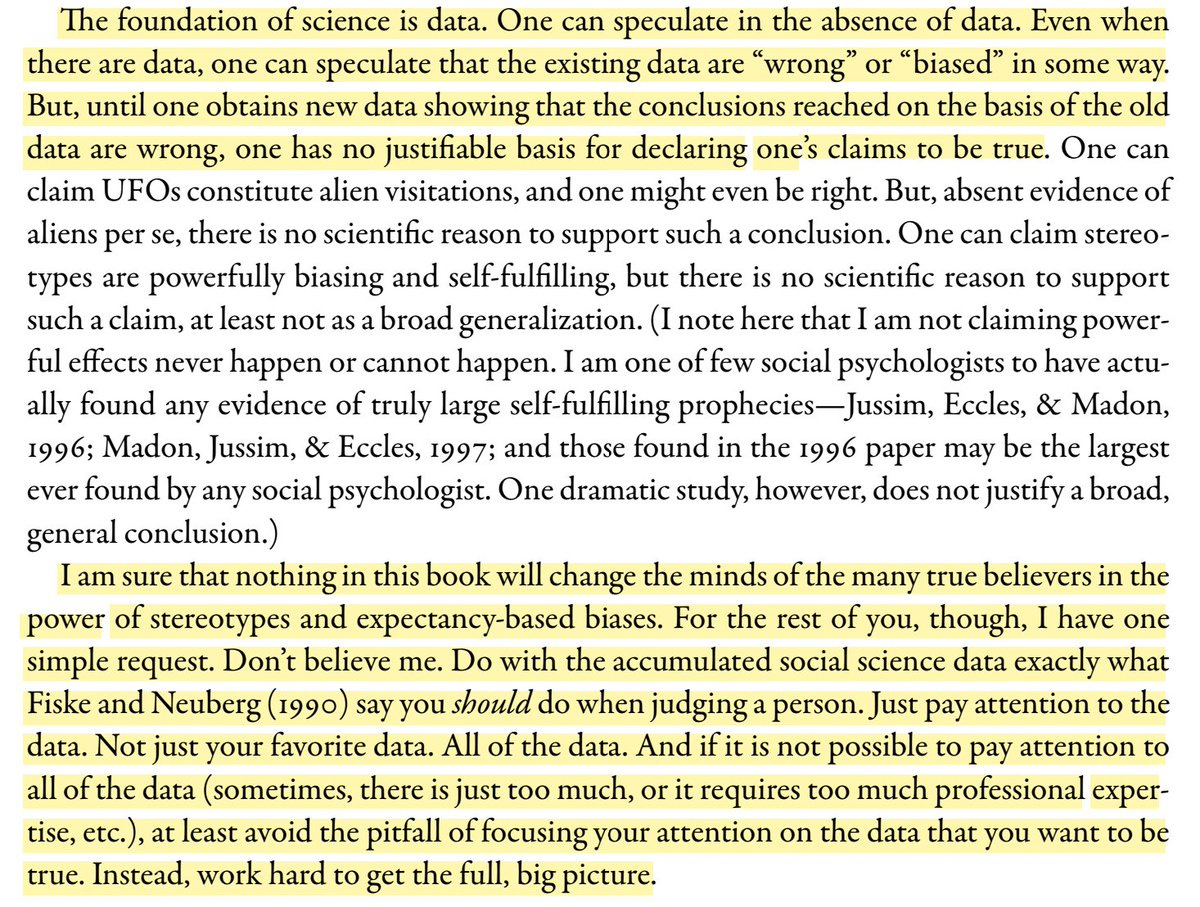

Highlights from Lee Jussim’s ‘Social Perception and Social Reality.’ A review of the social psychology literature on stereotypes and bias, which reveals how surprisingly GOOD we are at dealing with reality.

Dan Hopper

The book was published in 2012, and things may (or may not) have changed. (Lee here: Not much. None of the studies I reviewed have suffered debunkings or failures to replicate).2 Lee, however, uses scores (100s?) of studies to show how generations of well-meaning psychologists distorted our understanding of the way we interact with the world – so it remains relevant.

He argues that psychologists’ concerns about inequality have produced a ‘bias for bias’:3 their research has stressed how our ‘misbegotten beliefs and flawed processes construct not only illusions of social reality in the perceiver’s own mind but also actual social reality’. 3/

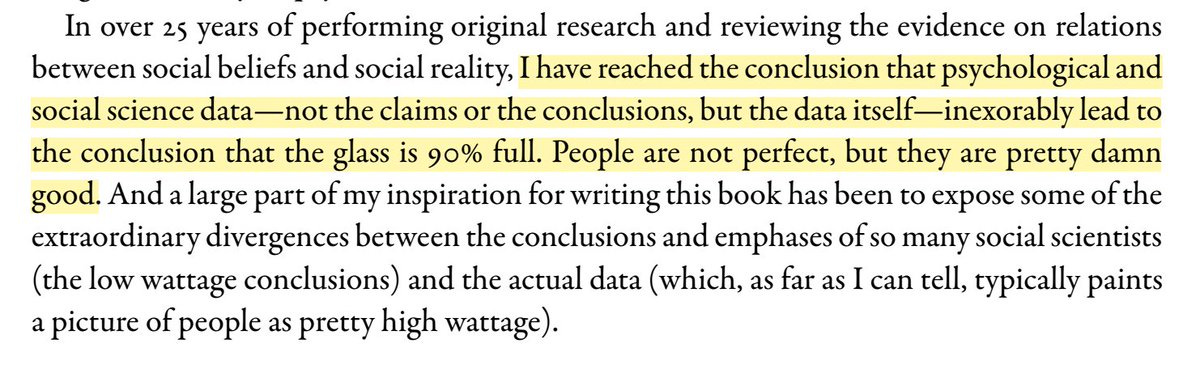

Jussim, conversely, argues we are ‘high wattage’. Studies showing how we suffer from (real) biases, also show how accurate we are – treating people as individuals (using stereotypes sparingly to increase accuracy). ‘People are not perfect, but they are pretty damn good.’ 4/

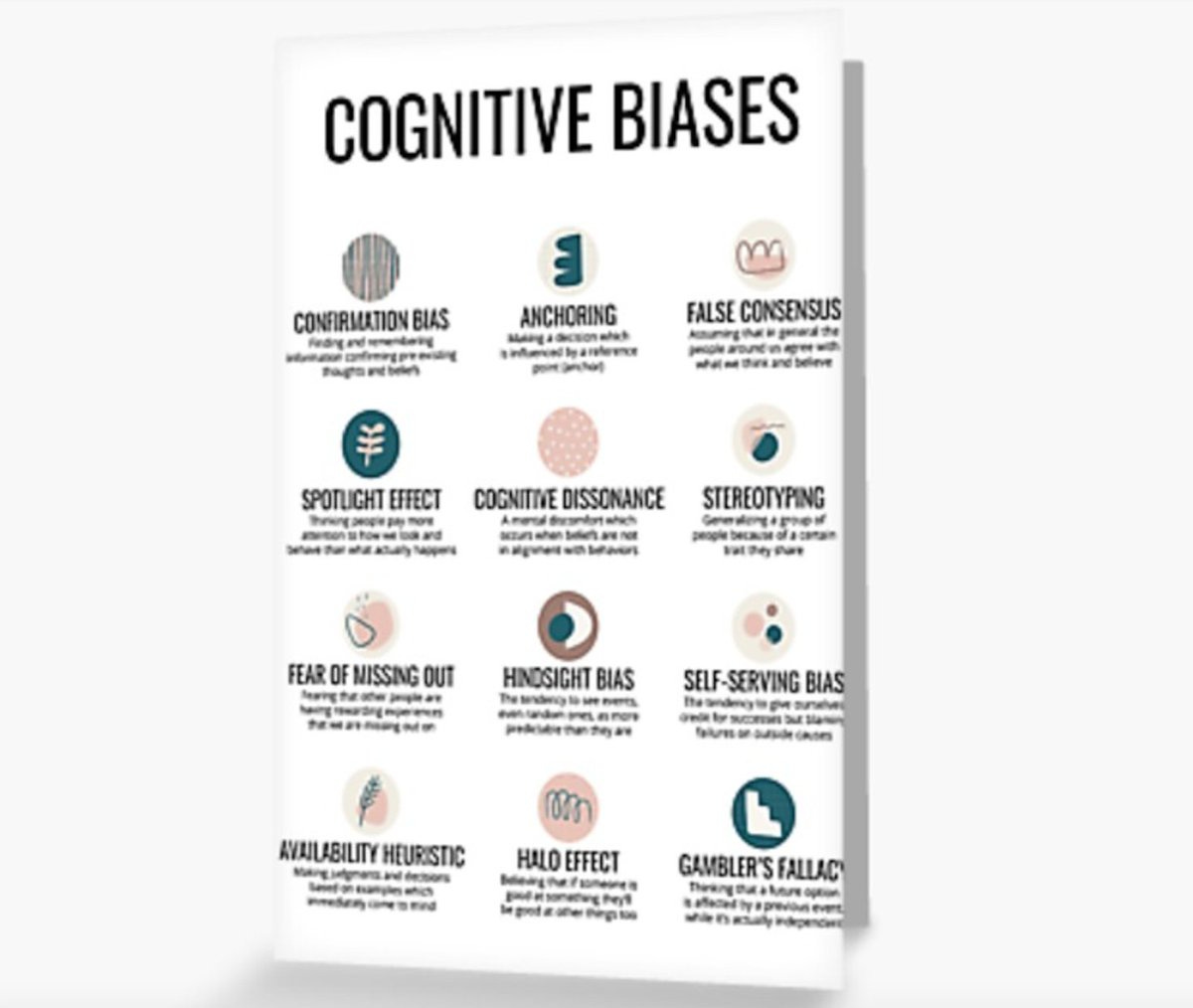

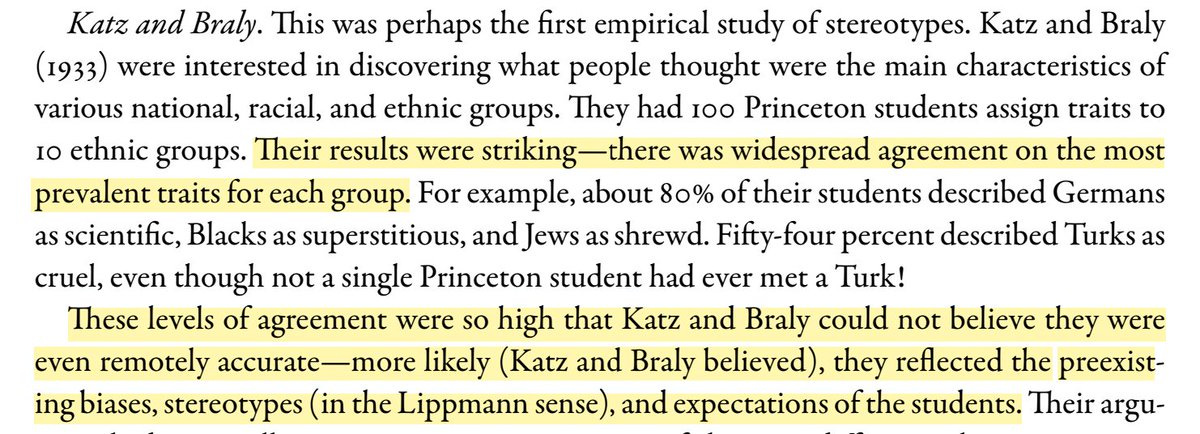

Early studies discredited ‘naïve realism’, showing how perceptions of reality (partly) ‘reflect our own fears, needs, and beliefs.’ It was journalist W. Lippmann (1922) who came up with the concept of a ‘stereotype’: a ‘picture in the head’, implicitly rigid, superficial. 5/

Katz and Braly (1933) ran with this, studying Princeton students’ views of national groups. Emphasising inaccuracy due to lack of experience, K&B contributed to the growing consensus that ‘stereotypes biased social perception and perpetuated social injustice.’ 6/

LaPiere (1936) further documented stereotypes by looking at views of Armenians living in California. Although he did make some attempt to assess stereotype accuracy, he appeared to confuse ‘inaccuracy’ and ‘dislike’ (a mistake: Jussim cites his own dislike of the KKK). 7/

These themes were systematized by G. Allport (1954), who set the research agenda for the next 50 years: stereotypes were rigid, ‘faulty exaggerations’, which were manifestly false because no groups’ ‘individual members universally share some set of attributes.’ 8/

Stereotypes also plausibly contributed to social injustice: in one study, Allport showed people pictures of a black man in a suit and a white man holding a razor; later, many ‘remembered’ the black man holding the razor and the white man wearing the suit. 9/

‘New Look’ psychologists (1940s/50s) focussed further on subjective influences on our perception – to the present day, their idea that ‘motivations, goals, and expectations influence perception [is] so well-established that it is largely taken for granted.’ 10/

One classic is Hastorf & Cantril’s (1954) American football study, showing that sports fans are biased about referee decisions. The problem, Jussim explains, is that the study’s results (despite the authors’ message) show ‘far more evidence of agreement than of bias’. 11/

Psychologists believed that our beliefs could construct social reality in two ways: 1) by influencing our perceptions; 2) by actually ALTERING reality itself (i.e., the behaviour of those being perceived). This second, more unsettling idea, was the ‘self-fulfilling prophesy’. 12/

There was some speculation on the self-fulfilling prophesy in the 1940s, but the idea took off during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, when Americans were highly sensitive to the role of racism in creating/maintaining inequalities – particularly in the classroom. 13/

Key here was R. Rosenthal’s ‘Pygmalion’ study (1968), named after the mythical Greek sculptor who fell in love with his own statue, bringing it to life. He tested changes in kids’ IQ when teachers were fed false info about which of them were promising ‘bloomers’. 14/

The results appeared to be that ‘late bloomers’ gained more IQ points than the control kids: what started only in the teachers’ minds translated into IQ gains. Teachers also liked the ‘bloomers’ more – surely, he had identified a ‘major contributor to social inequalities’? 15/

Not so fast, Jussim warns. ALL groups gained in IQ, & the difference between them ‘corresponded to an effect size of 0.30’ – not large. In fact, most of THAT difference came from the 1st & 2nd grade, and there were various inconsistencies that didn’t make sense. 16/

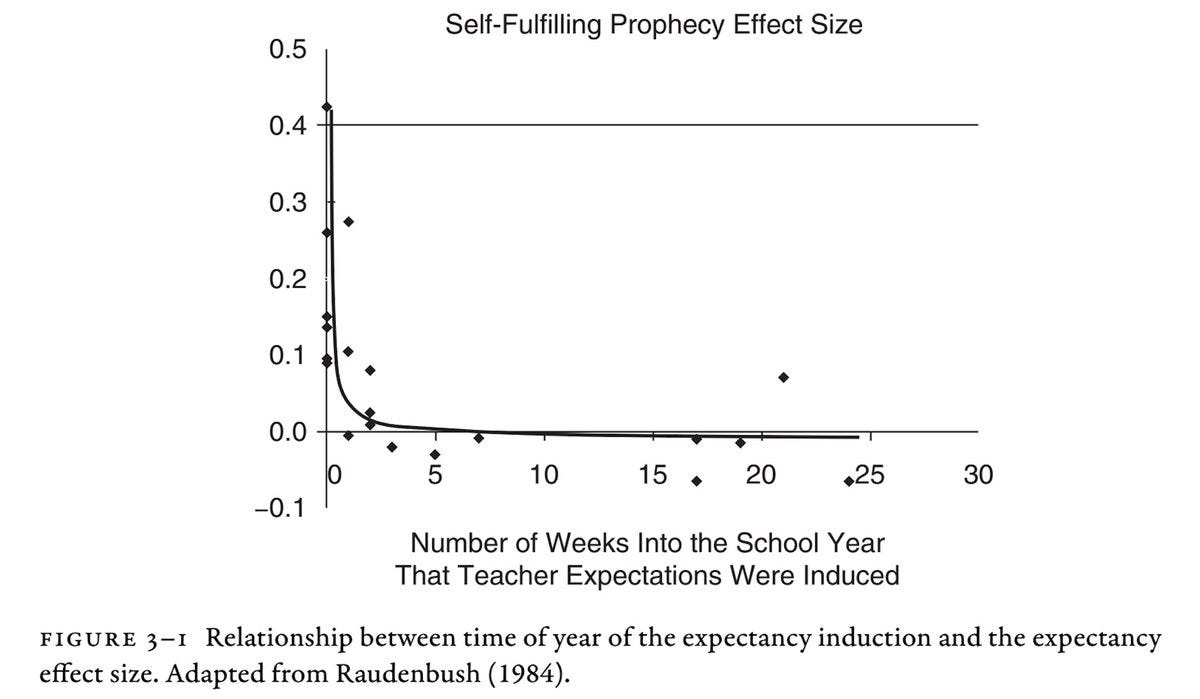

Hundreds of studies followed. Rosenthal himself developed the concept of meta-analysis, demonstrating that self-fulfilling prophesies were real. The effect on IQ, though, is disputed… Raudenbush’s (1984) metanalysis showed that it mattered WHEN teachers got false info. 17/

If teachers were misled in the 1st week of term, effect sizes closely matched the Pygmalion effect (r = 0.15), but quickly dropped off - after 2 weeks it had virtually no effect (i.e., a small effect was produced, but only BEFORE teachers got to know their students). 18/

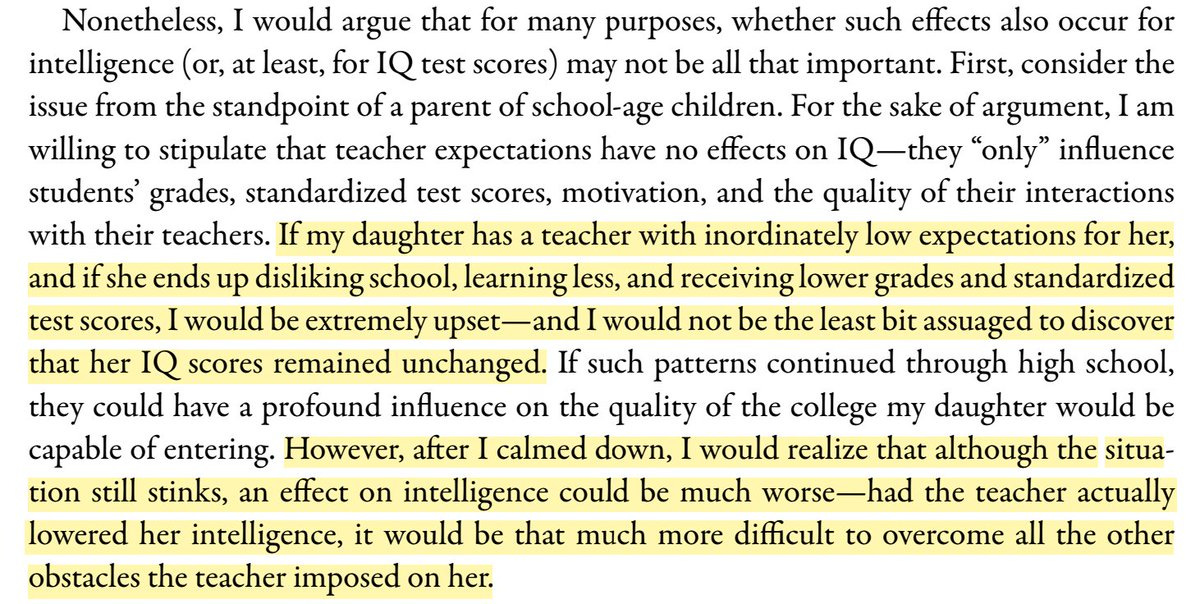

Pygmalion, then, doesn’t support the popular ‘story’ that ‘expectancy effects are powerful and pervasive, intelligence is primarily environmentally determined, and [that our beliefs] construct social reality’ (though they can, obviously, affect motivation & life outcomes). 19/

Returning to stereotypes. Having been put to such terrible use, historically, it’s understandable why many adhere to the belief that stereotypes are, by definition, inaccurate: ‘However, the accuracy of stereotypes is an empirical question, not an ideological one.’ 20/

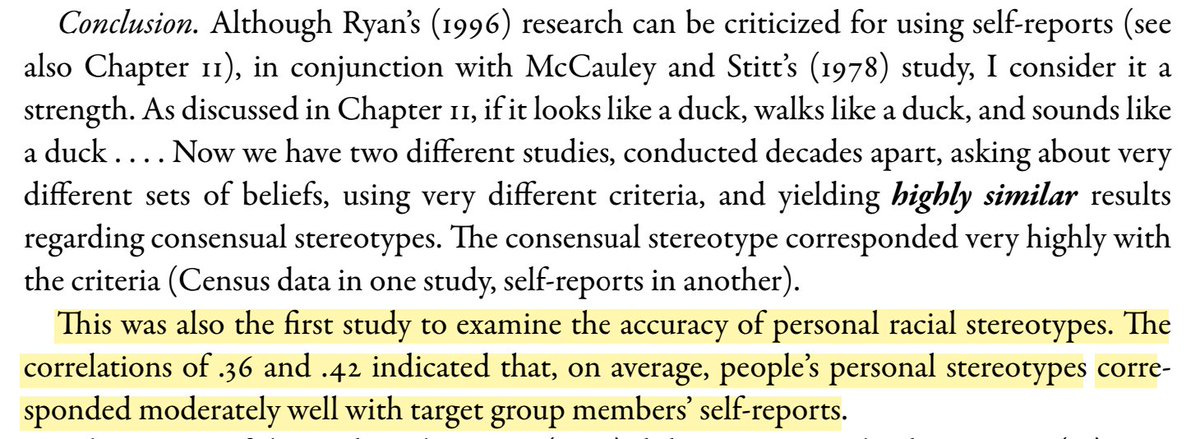

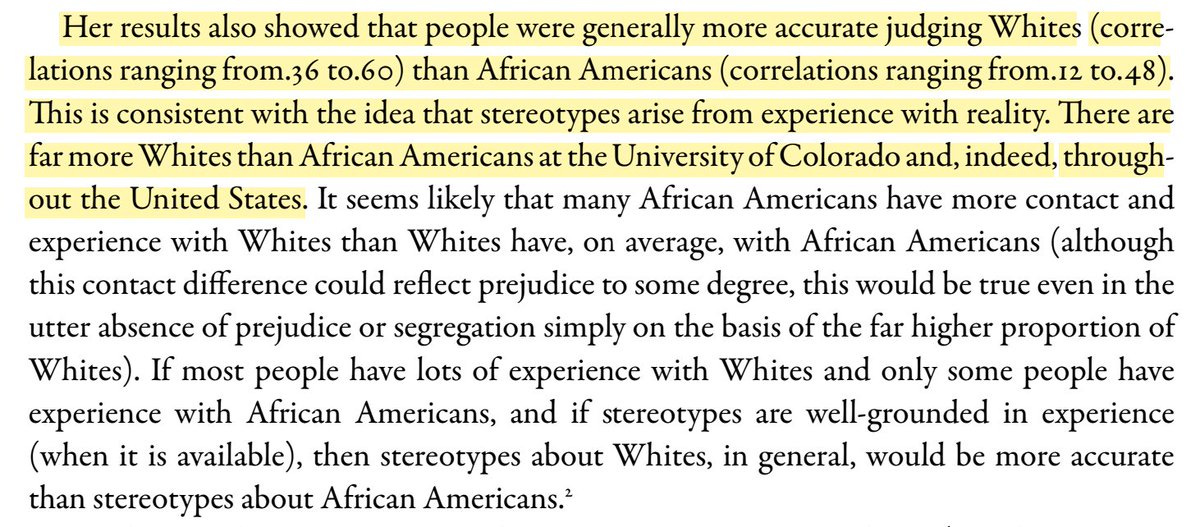

A study by C. Ryan (1996) on the accuracy of black & white American students’ perceptions of one another found 1) ‘strikingly high levels of accuracy’ across the board; 2) both groups were better judges of their own; 3) blacks’ stereotypes of whites were the most biased. 21/

This suggests: a) stereotypes are based on reality (knowing our own group best, & there being more white people to observe); b) bias did not function to support power (exaggeration, Jussim suggests, ‘may be more likely to appear when people’s group [ID is] threatened’) 22/

Perceivers’ IQ studies also support the idea that stereotypes are anchored in reality. Ashton & Esses (‘99) found smart people had more accurate stereotypes - apart from 1 group: ‘Brainy liberals were just as likely as dumb liberals to inaccurately minimize real differences.’ 23/

(Lee here. This next section cuts off some crucial prior text. Just prior, it reads, “…those scoring very low on” as in “those score very low on RWA…” RWA refers to rightwing authoritariansim).

Extreme (U.S.) liberals often ‘have a mindset emphasizing denial of differences, [so] their beliefs about groups [are] less accurate’. They ‘take the philosophical/political/spiritual idea that “deep down, we are all the same” too literally’, leaving them out of touch. 24/

Stereotypes have, of course, been used for evil, but pretending it’s never wise to ‘generalize’ can be dangerous too. A stereotype may or may not be accurate, but ‘People who cannot [or will not!] reach generalizations and abstractions are seriously cognitively impaired’. 25/

The claim ‘stereotypes cannot possibly apply to all individual members of a group’ is quite obviously true. The idea this ‘renders stereotypes inaccurate is, however, unjustified [&] confounds levels of analysis (population and either small group, individual, or both).’ 26/

Besides how accurate they are, then, a key question is how stereotypes are USED. ‘People who hold absolutist stereotypes undoubtedly exist… [such as] neo-Nazis. Nonetheless, such people are atypical of the participants in most scientific research on stereotypes.’ 27/

The question is, do the rest of us use stereotypes probabilistically? Are they ‘appropriately generalized, valid, rational, and flexible in response to new information’? In other words, do we use stereotypes to increase our accuracy, but switch to individuating info ASAP? 28/

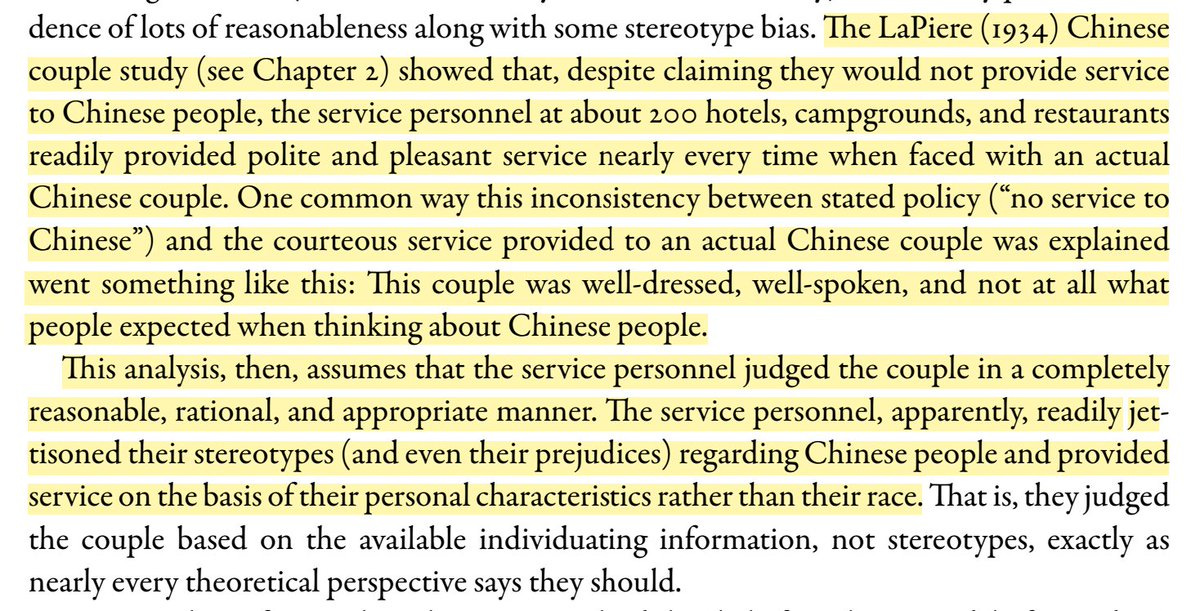

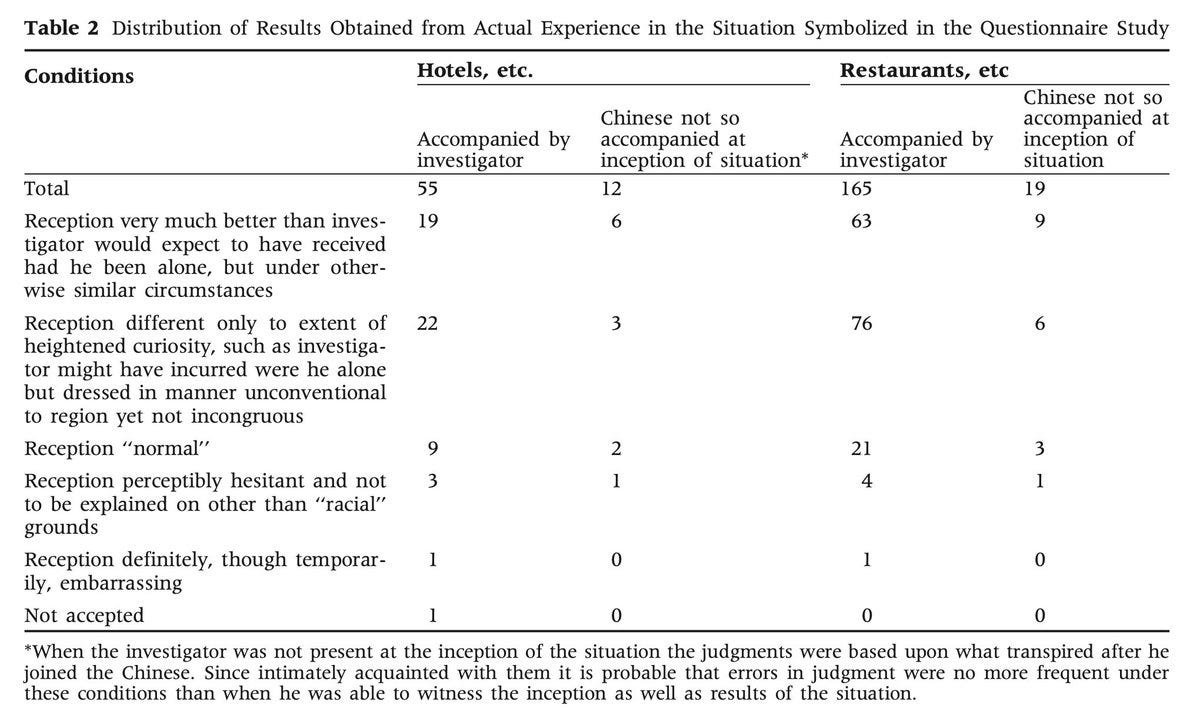

In 1934 LaPiere drove across the US with a Chinese couple, visiting 200 hotels, campsites & restaurants that refused to serve Chinese people. He found that they ‘readily provided polite and pleasant service nearly every time when faced with an actual Chinese couple’. 29/

Why? Because the ‘couple was well-dressed, well-spoken, and not at all what people expected when thinking about Chinese people.’ Accuracy of the stereotype aside, proprietors rapidly switched to judging them ‘based on the available individuating information’. 30/

The literature suggests, Jussim tells us, that people use stereotypes ‘when they have little other information about a target, [but] when they have individuating information, they use it, and they use it big time.’ Most of us judge others on their merits - as we ought to. 31/

In fact, the social psychologists have clearly had it the wrong way around: ‘The .10 average stereotype effect is one of the smallest in social psychology. The .7 average individuating information effect is one of the largest.’ 32/

The dominant ‘story’, still, is that stereotypes lead to inaccurate expectations, which are powerfully self-fulfilling. These self-fulfilling effects accumulate over time, ‘heaped upon the backs to those already most heavily burdened by disadvantage and oppression.’ 33/

The very studies this story is built on, however, show that the ‘power of expectations to distort social beliefs through biases and to create actual social reality through self-fulfilling prophesies is, in general… small, fragile, and fleeting’. 34/

Jussim goes further: the story ‘systematically distorts and overstates the evidence regarding the power of expectancies and stereotypes’. Although stereotype accuracy is ‘one of the largest effects in all of social psychology’, textbooks rarely mention it. 35/

Why, then, is the ‘story’ so popular? Why is there a ‘bias for bias’ within psychology? When so many ‘consider error and bias to be more important and interesting, we end up with a scholarship that overwhelmingly investigates and demonstrates error and bias.’ 36/

The story provides ammo for activists fighting oppression. Their resulting policies, however, could be ‘dysfunctional and produce unintended negative side effects’ if they refuse to recognise the ‘extent to which accuracy and non-discrimination may sometimes conflict’. 37/

It also undermines the credibility of social science by painting such an inaccurate picture: the truth is that ‘Accuracy dominates and error, bias, and self-fulfilling prophesy are the relatively unusual exceptions’ - the truth, Jussim states optimistically, always comes out. 38/

To sum up: hundreds of studies show that ‘stereotype effects [are] weak and easily eliminated, and that individuating information dominates person perception’. It is ‘only by an extraordinarily selective reading of literature that any other claim could be maintained.’ 39/

If you‘re happy to hear that you may not be a bigot after all, follow @The Dark Fiddling Pirate Jussim and read his book(s). This one ends with a reminder: ‘Don’t believe me… Just pay attention to the data. Not just your favourite data. All of the data.’ END

Addendum

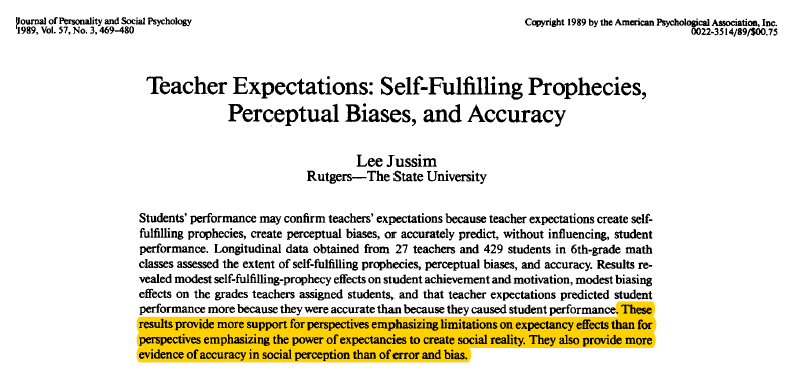

Lee here for a bit of an addendum. As early as 1989 I was publishing stuff skeptical of the social sciences’ overweaning emphasis on error and bias. This paper was based on my dissertation (completed in 1987).

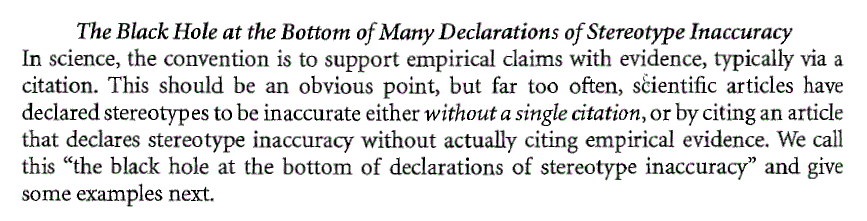

I spent most of the next 20 years on this type of work and research on stereotypes. Early on, I discovered that social scientists routinely made claims about the erroneous nature of stereotypes without evidence. In 2016, we published this paper:

In it, you can find this:4

Little did I know that my skepticism was just getting started and fundamentally similar problems (wild overstatement of claims, claims made without evidence, weak or dubious evidence, weak effects at best) characterized research on implicit bias, microaggressions, and stereotype threat.

Commenting

Before commenting, please review my commenting guidelines. They will prevent your comments from being deleted. Here are the core ideas:

Don’t attack or insult the author or other commenters.

Stay relevant to the post.

Keep it short.

Do not dominate a comment thread.

Do not mindread, its a loser’s game.

Don’t tell me how to run Unsafe Science or what to post. (Guest essays are welcome and inquiries about doing one should be submitted by email).

Footnotes (Lee here: I added all the footnotes)

The book is insanely expensive because it was an academic book and sold maybe a few thousand copies, mostly to libraries, and the publisher, Oxford Publishing, had to make money somehow (and even if it was cheaper it was probably too academic to have sold much more than that). I would never recommend that you pirate this book or any book. Pirating books is illegal and unethical. Therefore, you should make sure to avoid libgen, which is a book pirating outfit. The exact url is constantly changing because, like pirates of old, they are constantly being chased out of wherever they hunker down, and, also like pirates of old, they do shut down but reappear elsewhere.

However, you can also find an article length summary of the book here.

Have things changed much? There were subsequent studies on the (in)accuracy of stereotypes. Most confirmed the general pattern, but there were some exceptions. I was invited to participate in a series of adversarial collaborations empirically assessing the accuracy of a variety of stereotypes accuracy (before they were so named) by Macrae, the senior author of a 2000 study finding no accuracy in national character (personality) stereotypes:

That produced three papers. The first two, on the accuracy of gender and age stereotypes regarding personality characteristics, despite using very different methods than the studies reviewed in my 2012 book, confirmed the basic finding that such stereotypes were highly accurate. The third, however, which was a replication of the earlier “no accuracy in national character stereotypes” paper, found that the original finding of no accuracy also replicated. This was despite the fact that, to address issues I raised in the way they did the first study, the empirical analyses in the replication were much stronger.

The 2016 paper (linked above) also found that there is good evidence that people exaggerate political stereotypes (they tend to think there are larger differences between Democrats and Republicans and between liberals and conservatives than there usually are — note, however, this refers to laypeople, not the positions of elites, such as members of Congress; I am not saying their beliefs about members of Congress are wrong, but the stereotype accuracy studies have not addressed them).

Moral of this story: No one should be in the business of presuming that “all stereotypes are accurate” or, worse, that the general conclusion that the research has found lots of evidence of accuracy in people’s beliefs about groups means that your particular belief about any particular group is necessarily correct. It might be, but that can only be established by comparing your belief to the relevant data; it is not established by the research I have reviewed.

Scholars hold a bias for bias. There are many biases not addressed by my book, and, sometimes, people do hold beliefs that are out to lunch (various conspiracy theories, Qanon). They can often be pretty innumerate as well (wildly overestimating the proportion of the US population of various minority groups). These are not usually the type of interpersonal beliefs (i.e., beliefs Fred holds about Mary) or the types of stereotypes addressed in most of the social science research. On the other hand, there is good evidence for the Bias Bias, the idea that academics have biases that lead them to overstate the power, pervasiveness and inaccuracy of biases (see also this essay summarizing research finding that academics wildly overestimating sex bias in hiring).

Stereotype accuracy. Lots of “scholars” characterize this work as “controvesial” (often in scholarly articles) and outright wrong (usually on social media). As far as I know, however, none of it has ever been debunked and none of the findings on the accuracy of particular stereotypes has ever failed to replicate. Indeed, this paper came out recently:

So refreshing to see things like this. A nice dose of sanity. Thanks for sharing.

Helps confirm some of my experience- if you don’t flagwave your politics, people will more likely judge you based on your actions