Psychology Today: Censorship of Michael Scheeringa & My Resignation

On Their Removal and Unauthorized Revisions of Scientifically Justified Essays

This is a two part entry. The first part is by Dr. Michael Scheeringa, who describes his experience being censored at Psychology Today. The second part is my Letter of Resignation as a writer for Psychology Today for, if not exactly censorship, censorship-adjacent experiences

What is Censorship?

Many people seem to erroneously believe that censorship is something only the government can do. Any institution, organization, business, group, or individual who successfully prevents expression or dissemination of an idea has engaged in censorship. Retraction of articles that have been published after passing peer review, without identification of plagiarism, blatant data errors or fraud is usually a form of non-government censorship (for examples, go here or here). Censorship is not always illegal and (I would argue maybe in a blog for another day) often bad yet sometimes justified and even more often legal (yes, Virginia, some bad things can be legal). Nonetheless, especially in public forums (I am not referring to being sensitive to a family member’s feelings over dinner), something that prevents expression or dissemination may be legal, but it is still censorship.

What follows next is Dr. Scheeringa’s essay on how a blog he wrote describing his findings about “toxic stress”1 — which first appeared in a peer reviewed methods publication — was censored at Psychology Today.

My Psychology Today Blog Was Censored: Ideology, Censorship, and the New War in Psychology

Michael Scheeringa, MD. July 24, 2022

Lee’s note: The underlying controversy here involves the validity of the concept of “toxic stress.” The concept is wildly popular among academics and practitioners; a quick Google Scholar search on “toxic stress” yielded over 29,000 articles. Of course, scientific truths are not established by the frequency with which some term appears in the scholarly literature. Dr. Scheeringa published (in International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research) this 2021 review of empirical studies on toxic stress and found little support for its key hypothesis that stress alters the brain. I read it and found it quite good, though I did not do a deep dive to critically evaluate its every claim, although I did ask a colleague with expertise in this area to review it. He also concluded that it was a sound review (which does not mean it is some sort of Ultimate Truth That Can Never be Criticized). However, the idea that a perspective based on conclusions that appeared in a peer reviewed psychiatric methods journal is somehow inadequate to appear in Psychology Today strikes me as beyond absurd.

Dr. Scheeringa’s blog post is presented here in full, without further editing by me.

What Happened

Something remarkable happened recently. On January 27, 2022, I published a post on my Psychology Today blog site, titled Research Doesn’t Support Toxic Stress. And This is Worrisome. Five weeks later, Psychology Today took down my post and notified me by email after the fact.

For those new to the topic of toxic stress, this is the extraordinary theory that psychological stress and trauma can somehow permanently damage human brains. In the blog post, I explained that as I have investigated the true origins of the toxic stress theory over the past five years, I learned some enlightening things. I learned that the term “toxic stress” had been invented out of thin air when a pediatrician named Jack Shonkoff created the term as a marketing strategy. And then Shonkoff used the resources of his academic center at Harvard University to disseminate his message to legislators, judges, and educators to try to influence a slew of laws and social policies.

Then I explained how the research does not actually support this toxic stress myth.

Lastly, I explained in the blog the dangers of this movement, and how supporters of the toxic stress theory have successfully weaponized it by pushing ideologically-driven social programs on Americans. I explained how activists had implemented the toxic stress playbook in Baltimore, New Orleans, and in testimony before Congress on migrant children.

The editors at Psychology Today explained their action to block my post in their email with the following:

“Dr. Scheeringa, This article is herewith depublished. To be considered for republication, it will need comment from Dr. Jack Shonkoff incorporated into the piece, and detailed external citations . . . Thank you for understanding that content such as this must be bullet-proof and must adhere to journalistic standards.”

They made no mention about any complaints they had received.

Lee’s comment. Bullet-proof? No social science is “bullet-proof ” in the sense of being guaranteed to be invulnerable to credible challenge. This is true for most natural science as well, at least until such huge mountains of evidence are obtained, usually over many decades, that it becomes perverse to believe otherwise. And to hold up “journalistic standards” as some sort of rigorous ideal, given how much journalism routinely gets wrong, is more than a little odd.

My Appeals

I immediately replied by email asking if someone had complained. An assistant editor replied that Dr. Shonkoff and others had objected.

Next, I asked to see the complaints. Five days went by. No reply. I asked again, and received a reply that I would not be allowed to see the complaints. Instead, the editor expressed three concerns about my blog. First, the complainants believed that my dismissal of toxic stress was contradicted by a large body of peer-reviewed research. Second, the complainants believed that I misrepresented the motives of those who research toxic stress by asserting that the term was invented for marketing purposes. Third, Dr. Shonkoff complained that my summary of his congressional testimony stated the opposite of what he said under oath.

Within a few days I responded to these three concerns with an 803-word email. First, I provided more peer-reviewed research references that supported my position, including the only two literature reviews on pretrauma, prospective, longitudinal research which agreed that little to no evidence supports toxic stress. All studies cited by supporters of toxic stress are cross-sectional designs that have no causal explanatory power. Second, I explained how the activists themselves have bragged about how they invented the phrase “toxic stress” for marketing, and provided the source material. I used the activists’ own words to back up what I wrote. Third, I quoted Shonkoff’s congressional testimony verbatim (I have also since provided the video of his testimony in my YouTube post). I had written in the blog that Shonkoff testified before a Congressional subcommittee that the administration’s practice of temporarily separating migrant children from parents in a holding camp is toxic enough to permanently damage children’s brains for the remainder of their lifetimes, which is exactly what he said in his testimony.

Even though I thought it was absurd, I even contacted Shonkoff to get his comment as Psychology Today demanded. I sent an email to Dr Shonkoff, and cc’d Psychology Today, which explained the situation, including it must have his comments, and asked him to comment. Shonkoff replied simply, “No thank you.”

Even though I reached out to Psychology Today six times, provided everything they asked for, and had met all their conditions, they still refused to republish my post and closed the book on the matter.

Why Did They Censor Me?

The reason given by Psychology Today is that I failed to meet their journalistic standards. There are at least two problems with that. First, blogs are opinions and commentaries written by amateur journalists, and are not professional journalism. It’s not clear to me that their journalistic standards are appropriate for blogs. Second, I did eventually meet all their standards and they refused to publish it anyway. The only thing I didn’t provide was a thoughtful comment from Shonkoff but that’s because he refused. In standard journalistic practice, I believe “No thank you,” which is the same as “No comment,” is the same as a comment.

It is noteworthy that the Psychology Today blog site is filled with posts by many bloggers about unproven theories, unsupported speculations, and articles about people who have not been asked to comment. If the editors imposed the same standards on their bloggers that they imposed on me, they would probably have very few posts.

For context, this was the 50th post I had published on that site since 2017. It’s not the first time I’ve posted something controversial. I’ve had discussions with editors in the past about several of my blogs and they’ve never unpublished a post before. For example, in 2020 I posted a blog that was critical of play therapy as a treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in children. Multiple play therapists privately complained to Psychology Today. Rather than depublish my blog, they encouraged one of the play therapists to post a counter argument, and then I posted my reply. Why couldn’t that have happened again?

It is also noteworthy that many of the bloggers on their site are very supportive of toxic stress. It appears that only one viewpoint about toxic stress is allowed by Psychology Today.

Even if my alternative viewpoint is wrong, why can’t my viewpoint be heard? That’s the real strangeness of this situation in that even if others don’t agree with me, how does this lead to silencing a legitimate scientific interpretation that happens to be different? There seems to be something different about this topic compared to all the other controversial topics. What could that be?

What Does It Mean?

Two things happened here that signal ominous times ahead for science, public policy, activism and the media. First, I was attacked by scientist activists because my expert opinion disagreed with theirs. That Dr. Shonkoff and the other supporters of toxic stress complained and tried to cancel me was not surprising. They have made it clear that they are pursuing a radical, activist agenda to leverage weaponized neuroscience to make major social policy changes in America. They have a lot invested in toxic stress being true, and they know now that I’m discrediting them with actual research.

Shonkoff and toxic stress supporters are ideological activists. There is nothing in inherently wrong with that. Psychologists and other scientists have always engaged in activism. There have always been debates. Think what you want of Shonkoff and company’s efforts, they’re allowed to attempt activism, but they’re not allowed to silence opponents.

Which brings me to the second thing. A major media outlet, Psychology Today, caved to the complaints and censored me from their platform. They could have said they were depublishing me because they don’t agree with my opinion. That would constitute partisan journalism but at least it would be honest.

Since then, the editors have changed their publishing policy. They no longer allow authors to immediately post their blogs. All blogs, supposedly, are reviewed by editors before being allowed up on the site.

We’ve seen this new trend of social media giants (i.e., Facebook and Twitter) deciding unilaterally what’s truth and what’s misinformation. Psychology Today has taken a side with the toxic stress activists. They have crossed that line, along with Facebook and Twitter, that they will decide what is truth and what is misinformation without regard for scientific evidence.

And this is worrisome.

P.S. I’ve posted the original, uncensored blog on my personal website at michaelscheeringa.com. It is called Research Doesn’t Support Toxic Stress and this is Worrisome.

P.P.S. This article is an abridged version of my YouTube video titled My Psychology Blog Was Censored. Who Does That?

P.P.P.S. If you’re interested in more detail about the real research behind the myth of toxic stress, Dr. Shonkoff, his private center at Harvard, and the whole background story on the invention of toxic stress, those are covered in detail in my book, The Trouble With Trauma, and in other videos on my YouTube channel.

Dr. Scheeringa is in the midst of a career shift. In June 2022, he resigned from a tenured position after 29 years in academia so that he can run his new company to launch a mental health app and provide commentary as a conservative psychiatrist on trauma and other current affairs in science. He is the author of the book published this year titled The Trouble With Trauma: The Search to Discover How Beliefs Become Facts (Central Recovery Press). More information can be found at his website www.michaelscheeringa.com.

I apologize for the length, but these two essays seemed like they belonged together. The next is my open letter to Psychology Today explaining why I am giving up my position blogging for them. Lee

My Resignation from Psychology Today

Lee Jussim

Dear Psychology Today,

It is with more than a little sadness that I find myself compelled to resign as a blogger for your site. I started over ten years ago, and have posted over 100 blogs that have been viewed well over a million times. I did it mostly to get ideas out to a wider public than I could reach via scholarly publications; I also did it to improve my own skills at writing about social science issues outside of peer review. I think I succeeded at both. Furthermore, over the last few years, some of those blogs inspired work that appeared in my more scholarly publications. Thank you for providing me that opportunity. I note that all of that goodness occurred because for most of that time you left me free to pursue my social science muses however I so chose. This was an excellent policy.

A Good Run

Its been a good run. You seem to have thought so too, given how many of my posts (especially in the last few years) you promoted to Essential Reads, the blogs you highlight on the main Psychology Today site.

So why resign now? Because, Psychology Today, you changed. From 2012 through 2020, I had almost complete latitude about what to write and how to write it, most without any editorial input or interference. This was a great recipe.

You Changed the Recipe

That is no longer true; you changed the recipe, and the new one leaves a bad taste in my mouth. Almost every draft post of mine over the last year has been caught in a web of new editorial rules, obstruction, ignorance-driven-disputes, and capricious changes to my titles or texts made without my approval and without even consulting me. In what universe did you come to the conclusion that this was a good way to run a blogging platform?

Put differently, your editorial policies and practices have become a prohibitive pain in the ass.

I can no longer invite a guest to do an essay and post it. Now, I require negotiations with and approvals from your editorial staff to do so.

You now limit posts to 1000 words, with a hard limit at around 1300. My most widely-read post, with over 125,000 page views, has over 1800 words. In third place, with over 60,000 views, is this blog, which is over 2000 words. Not every piece of writing needs to target Short Attention Span Theater. People do love “8 Ways to Tell if Your Lover is a Narcissist” (a common theme in popular Psychology Today blogs), but they also hunger for quality, sophisticated, in-depth, rigorous social science-informed analysis.

Your editors now routinely change my titles, and sometimes the text, without discussing this with me, let alone asking my permission. A blog that I titled , “The Science Shows You are not an Unconscious Racist” was published as “12 Reasons to be Skeptical of Common Claims about Implicit Bias.” The original title is more factually correct and informative, because the science has never shown that whatever is measured by implicit methods is “unconscious.” Regardless of the merits, changing the title without consulting me? WT living F?2

The blog titled “The Dubious Science of Microaggressions” was changed to “The Problem with Research on Microaggressions,” again, a worse and even misleading title, because there is no “the” problem with microaggressions — there is a myriad of problems, so many that few, if any, of the claims common in the social science “scholarship” on microaggressions should be believed.

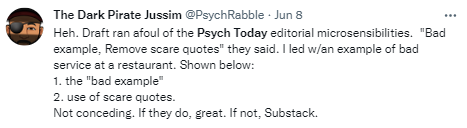

The same microaggressions essay was withheld from posting because one of your editors objected to my use of a concrete example involving bad service at a restaurant as an example of something that microaggression advocates have called a microaggression but which was obviously not a microaggression. I was told it was a bad example. I now had two bad options, bad because both were wicked time sucks: I could rewrite the example or track down the peer reviewed articles that used this example. I chose the latter and then commenced another negotiation over content via email; what a worthless timesuck. These negotiations took so long that I threw in the towel and posted the essay on my Substack, with the original title, which you can find here. That post has already received more page views than the one you eventually posted at your site, which is amazing considering how well-established Psychology Today is and how much my Substack is still a relative unknown.

I had a long, protracted negotiation with one of your editors who labored under the illusion that referring to people on the political left as “left” was some sort of insult. It was only after tracking down and emailing a slew of peer reviewed articles that refer to people on the left and right as on the “left” or “right” that I was able to convince your editor that “left” was simply descriptive and not an insulting denunciation by some rightwing extremist.

Each one of these are just examples; there are many more like this. Writing is hard enough; having to educate your editors, people who generally lack the social science expertise to have an informed opinion for essay after essay is not my idea of a good time. This problem was especially likely to rear its ugly head when I wrote something critical of either social justice research or which highlighted flaws and biases on the political left. I ran into no comparable problems when I published a blog on The Discrimination Paradox which argued that even though acts of discrimination might be infrequent, experiences of discrimination by those targeted might be substantial. Funny that.

Don’t get me wrong; I am fine with fact-checking; and the rare times your editors have found an error (say, when I got someone’s first name wrong), I always changed it. That was useful editorial intervention. But title-changing? Arguing over whether “left” is an insult? Delaying posting till I prove to you that microaggression researchers used exactly the type of example I used? This was the writing equivalent of driving 65mph in a 65mph zone and being stopped for speeding and having to go to court over and over to prove my innocence. Time to find another route and avoid the overzealous editorial cops.

What once was an intellectually edifying experience and a cheap way for you to get page views based on sound science and rigorous analysis became a miserable experience. Every essay became a tortured slog through your editors trying to impose their erroneous beliefs on my essays. The cost of writing inherently includes the time to draft and revise plus the time to pretty it up on the (clunky 1995-vintage functionality) Psych Today website. But adding to that cost, I now had to force my writing into your word limits and then be prepared for a Medieval jousting match with your editors every time I wrote something critical of social justicey “scholarship.”

Oh Snap! A Wrist Slap

And then came the straw that broke my camelian back. While your editors were angsting over my essay on microaggressions, I tweeted this:

Shortly after posting this, I received a terse email from an editor reminding me that Psychology Today’s guidelines prohibit writers from making “negative comments” about Psychology Today. “Microsensibilities”? You were upset enough about that to send me a wrist-slapping email?

I will never again violate those guidelines because I am no longer bound by them; I am no longer writing for Psychology Today.

To be sure, Psychology Today, you have the right to run your business any way you please. Maybe all these practices make great business sense in some way that is not obvious. Who needs a ~2000 word essay packed with social science data and critical analysis that gets over 100,000 page views? Not you.

The Power of Freedom

Although my personal politics are left of center, I somehow avoided the bureaucracy-is-great! delusion that seems characteristic of so many lefties. When I was Dept. Chair, faculty interviewing often asked what my vision was for the Dept. I’d reply:

“I have no vision. That is because the people in the best position to have a vision for their own work and where it should head are those people, not me. My job, as chair, is to make it as easy as possible for them to do their work, to follow their own visions, not mine.”

Since the microaggression fiasco, I have not written for you, Psychology Today, and have moved my regular blogging to Substack, which has a far more liberal policy of mostly non-interference. I have now posted 8 blogs in 3 months (including this one), about double what I had been recently doing for you; this is the unleashed power of freedom. They, too, are a private company, and can change their mostly non-interference policy at any time. But you, Psychology Today, have implemented an editorial regimen that is onerous, and Substack has not.

Is the editorial interference I experienced a form of censorship? No. But its not “not censorship” either. Changing my words without permission, removing phrases, making it sufficiently difficult to actually post something that I posted fewer things? Let’s call it “not censorship exactly, more like censorship-adjacent.” Not illegal, and well within your rights, Psychology Today. But its not always wise to exercise a right just because you have it.

I am truly sad to exit what had been a wonderful relationship, Psychology Today. But it was you, not I, that changed.

Lee Jussim

On scare quotes. Inasmuch as Psychology Today upbraided me for use of scare quotes, I am thoroughly enjoying using them liberally throughout this essay. Oxford defines “scare quotes” this way: “quotation marks used around a word or phrase when they are not required, thereby eliciting attention or doubts.” Bad scholarship, or scholarship that has been subject to rigorous criticism, is justifiably flagged by scare quotes. It might be right, but you should have doubts!

On editors changing titles. Yes, I know that newspaper and magazine editors routinely print articles, essays, and op-eds with titles of their own choosing. But this a blog site, not a magazine or newspaper.

Thank you for teaching me (30 years ago) how to be a critical thinker — so important to fighting group think. Would love to catch up, Professor!

Brilliant, Professor. Thank you.