No Evidence for Workplace Sex Discrimination

As Per Most Rigorous Psychology Meta-Analysis Yet Performed

This is a modified for comprehensibility (I hope!) excerpt from a draft manuscript by Nate Honeycutt and me to be submitted for peer review. The larger paper is on how psychology has periodically experienced explosive paroxysms of research on bias, only to discover that either the work was unreplicable, overblown, or that the “biases” discovered actually serve people quite well in the real world.

But the real star here is not us. It is the paper (not by us) that we describe here.

A recent meta-analysis examined 85 audit studies assessing workplace sex discrimination, including over 360,000 job applications, conducted from 1976 to 2020 (Schaerer et al, 2023).

A Word for Non Nerds

Readers of Unsafe Science include natural scientists, social scientists, academic non-scientists, professionals in other fields, and regular people who are not lawyers, professors or other professionals (yes, I think most of us not in that last category of regular people are kinda “irregular” in many ways1, but I digress). To understand the rest of this essay, you will need some familiarity with terms like meta-analysis, audit studies, and statistical significance. These terms are really not that complicated to understand sufficiently for this essay to be comprehensible. However, if you are not familiar with them, I highly recommend skipping to the Appendix at the end that defines these and other technical-ish terms, reading it first, and then returning here. If you are fine with all those terms already, read away…

Back to the Meta-Analysis

The audit studies in the meta-analysis examined whether otherwise equivalent men or women were more likely to receive a callback after applying for a job.

The meta-analysis had two unique strengths that render it one of the strongest meta-analyses on this, or any other, topic yet performed. First, the methods and analyses were pre-registered, thereby precluding the undisclosed flexibility that can permit researchers to cherrypick findings to support a narrative and enhance chances of publication. Few existing meta-analyses in psychology on any topic have been pre-registered. Second, they hired a “red team2” – a panel of experts paid to critically evaluate the research plan. In this particular case, the red team included four women and one man, three had expertise in gender studies, one was a qualitative researcher, and one librarian (for critical feedback regarding the comprehensiveness of the literature search. The red team critically evaluated the proposed methods before the study began, and the analyses and draft of the report after the study was conducted.

Key Results

1. Overall, men were statistically significantly less likely than women to receive a callback. Men were, overall, 9% less likely to receive a callback than were women.

2. Men were much less likely than women to receive a callback for female-typed jobs. Men were 25% less likely than women to receive a callback for these jobs.

3. There were no statistically significant differences in the likelihood of men or women receiving callbacks for male-typical or gender-balanced jobs. English translation: callbacks were nondiscriminatory.

4. Analysis of the discrimination trend over time found that women were somewhat disadvantaged in studies conducted before 2009 after which the trend reversed, such that there was a slight tendency to favor women after 2009.

5. People high in system justification were less inaccurate than were those low in system justification, a result that contrasts sharply with research that typically emphasizes the many biases of those high in system justification (Jost, Glaser, Kruglansi & Sulloway, 2003).

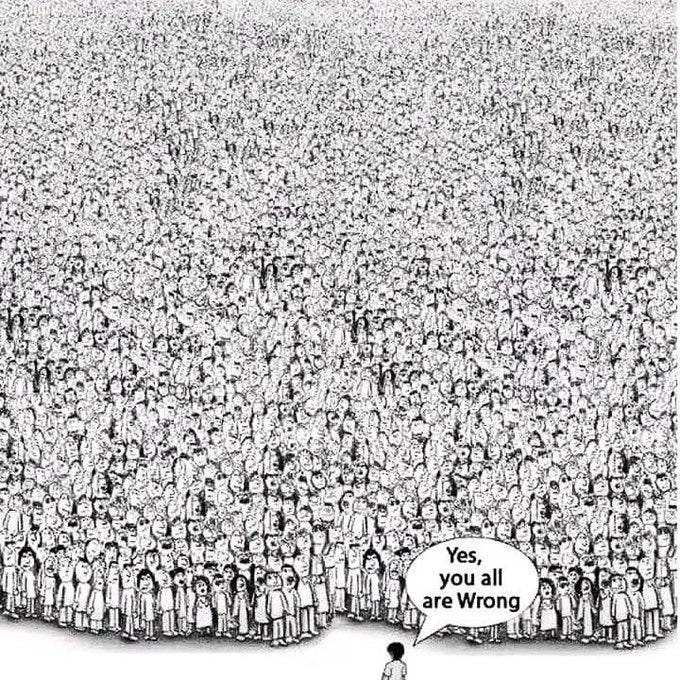

6. The research team also had both laypeople (N-499) and academics (N=312) predict the results of their meta-analysis. All vastly overestimated the amount of bias favoring men and erroneously predicted that that bias persisted into the present, although laypeople were somewhat more inaccurate than were academics. The overestimates were dramatic, with laypeople estimating that men were three times more likely to be called back than women even in the most recent period they studied (2009-2020). Academics were not quite as bad, but still pretty awful given that one might think the whole PhD thing would confer some higher level of knowledge about these sorts of things. Academics estimated that men were twice as likely as women to be called back for jobs in the 2009-2020 period (for both groups, the overestimates were more extreme the further back they went).

The Abject Failure of the Academic “Experts”

7. The final finding I will discuss here is this: Academic (supposed) expertise made no difference – academics who had published on gender were just as inaccurate as those who had not. Such people should know better. This result is worth cozying up with for a bit. It reflects a staggering failure of academic “expertise.”

In some sense, these academics were asked to make a “prediction” — one regarding how the results of the not-yet-performed meta-analysis would turn out. But in another sense, it was no prediction at all — it was a test of how well they knew the findings in a research area in which they were supposedly experts. That is because the meta-analysis was not really a “prediction” about “future” findings. It was a summary of what has been found by past research going back to 1976. You might think that “experts” would know the findings in exactly the area in which they supposedly have “expertise” (silly you). These academics dramatically failed that test.

Keep in mind how extreme the failure was (predicting men were twice as likely to get callbacks when in fact men were 9% less likely to receive callbacks). Now think about all these wrongheaded academic “experts” promoting their “knowledge” to other academics, the wider public, and their students. This is how you get a field filled with propaganda and bullshit.

Limitations

The meta-analysis did not address every conceivable type of sex discrimination. It is possible that there is much more evidence of sex discrimination in other contexts (e.g., actual hiring, promotions, salaries or different types of jobs). It is very difficult for experimental studies such as those in this meta-analysis to examine actual hiring decisions because one would need real people (rather than, e.g., resumes) who answer callbacks, go for interviews and ultimate do or do not receive jobs. The vastly greater time and attention it would require of businesses doing the hiring of fake applicants also would render such studies probably undoable because of ethical issues (they would be exploiting large investments of company time and effort for the scientists’ research purposes).

Thus, experimental audit studies are probably about as good as we can do to assess levels of sex (or other) discrimination in the real world. Note that I wrote “sex discrimination” rather than “discrimination against women.” Sex discrimination (as they discovered) can go either way; but an absence of evidence provides … no evidence either way.

Conclusion

As the authors put it in their conclusion: “Contrary to the beliefs of laypeople and academics revealed in our forecasting survey, after years of widespread gender bias in so many aspects of professional life, at least some societies have clearly moved closer to equal treatment when it comes to applying for many jobs.”

Their results, however, do raise an interesting question: Why do so many people, especially academics who should know better, so wildly overestimate sex discrimination? That, however, is a question for an essay another day.

References

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political Conservatism as Motivated Social Cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 339-375.

Schaerer, M., du Plessis, C., Nguyen, M. H. B., van Aert, R. C., Tiokhin, L., Lakens, D., ... & Gender Audits Forecasting Collaboration. (2023). On the trajectory of discrimination: A meta-analysis and forecasting survey capturing 44 years of field experiments on gender and hiring decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 179, 104280.

Footnotes

(Ir)regular people. Professional elites, especially on the coasts, like me, tend to inhabit economic, political, and intellectual bubbles leading them to develop ideas about which they are supremely certain that not only seem strange to regular people, but, in my opinion, actually are quite strange on their merits. I am not alone in this — Thomas Sowell wrote a whole excellent book about it, called Intellectuals and Society, which, at least as of this writing, you can listen to for free on Youtube. This is not to romanticize regular people either (see, e.g., point 5 in the above list of results for the study). Although I am not immune to these bubbles, I am pretty sure I have some measure of innoculation, though I do not want to overstate this because its a good metaphor (most vaccine’s work but they are rarely guarantees). I attribute whatever level of intellectual innoculation I have to the following experiences. 1. I grew up just above poor, in a public housing project. I was born in 1955. I’d say it wasn’t until around 2000 that I had a sufficient income to feel like I wasn’t one disaster away from not being able to pay the bills. That’s 45 years; its enough time for it to be indelibly etched in my psyche. The great thing about growing up poor is that it really grounds you — having your head in a metaphorical guillotine tends to focus one’s attention on what really counts, and let the Devil take the hindmost. 2. I play competitive sports. Issues of fairness, bias, and the reality of … reality, comes up all the time in competitive sports, as I pointed out in My Positionality Statement. 3. I am active on Twitter. Everyone who is active on Twitter knows it can be a Hell Hole. Regardless, its great strength, and the reason I am still on it, is that it puts me in touch with LOTS of people outside my professorial leftist coastal bubble, many of which are ready, willing, and able to call bullshit. They are not always right, but that is not the point — which is, instead, they help keep me grounded.

Red Team. As per Wikipedia: Red team is a group that pretends to be an enemy, attempts a physical or digital intrusion against an organization at the direction of that organization, then reports back so that the organization can improve their defenses.

Appendix: Methodological and Statistical Terms and Definitions

Some Definitions for Nonexperts

If you are an academic social scientist, you can probably skip this section. If you are not familiar with these terms, you will need them to understand why this paper is so good.

Statistical significance. DO NOT confuse this with “importance.” Statistical significance has a highly technical meaning that I am not going to bother with here involving null hypotheses and probabilities. Without spending a few semesters in good stat courses (bad ones often get the technical meaning wrong), suffice it to say this functions as a threshold whereby researchers are greenlighted to take seriously as “real,” whatever difference or relationship the term is applied to. This is to be contrasted with typically minor differences that result from noise or randomness, which does not give researchers the green light to take their results seriously.

Meta-analysis is an array of methods used to combine and summarize results from many studies, in order to figure out what the big picture is. It is sorta like taking an average (though in practice a bit more complicated). Has prior research consistently found the effect? If so, how big or small is it? Is the effect different for different types of studies on the same topic? How much have researcher or publication biases distorted the main findings?

Audit studies are one of the strongest methodological tools available for assessing discrimination. First, they are experiments, so they are excellently designed to test whether bias causes unequal outcomes. This is in sharp contrast to studies that merely identify “gaps” (inequality in some outcome across groups). Such studies are routinely interpreted as evidence of discrimination, even though discrimination is only one of many possible explanations for gaps. In audit studies, targets who are otherwise identical (e.g., identical or equivalent resumes) differ on some demographic characteristic and apply for something (such as a job). Thus if Bob receives more callbacks or interviews than Barbara, the result can be attributed to sex discrimination. Second, they are conducted in the real world, for example, by having fictitious targets apply for advertised jobs. These two strengths – strong methods for causal inference and tests conducted in the real world – render audit studies one of the best ways to test for discrimination.

Pre-registration. This refers to preparing a written document stating how some study will be conducted and analyzed, including how hypotheses will be tested, before the research is actually conducted. This was one of the reforms that emerged from Psychology’s Replication Crisis. It prevents researchers from conducting some study, performing ten zillion analyses and cherrypicking a few about which they can tell a good story without saying so, thereby conveying the false impression that they are brilliant and that their theory, hypotheses and results are credible. It also prevents researchers from failing to report studies that found no hypothesized effects or relationships at all. In short, it dramatically reduces researchers’s ability to make themselves look like sharpshooters when they are just making shit up. Like this:

I would have hypothesized that academics make worse predictions than the general public as they 1) are more removed from the business of typical workplaces and 2) are more ideologically homogeneous. So I'm pleasantly surprised with that result, tbh. I wonder how it would look with academic jobs. Would there be bias? Would academics be more accurate?

This is excellent, I shared it on Twitter. I hope it is widely cited and used