My Positionality Statement

Tennis anyone?

What are Positionality Statements and Why am I Writing One?

Positionality statements are all the rage in academia. The term “positionality” comes from ideological frameworks that view things (almost?) entirely through the “lens” of power, status, and oppression. Just do a search or Google Scholar search for “positionality” or “positionality statement” and you will get an eyeful.

Different advocates will say somewhat different things about positionality statements, but the core idea, at first glance, may seem reasonable: Researchers should reveal to the world how their identities or worldviews might influence or bias their research. Now, it is certainly true that their identities or worldviews might influence or bias their research. So what is the problem? So might everything about the researcher — their experiences, personality, theories, public commitments, political views, religious views, tastes, marital status, family size, birth order, social networks, collaborative networks, goals, income sources, and pretty much anything else. To take it seriously quickly renders the effort absurd. Or, as I put it here, “Given that a person’s positionality is some combination of their very long list of statuses, demographics, identities, beliefs, values, and experiences, indeed, it is the sum total of everything they are, identify with, have experienced, and have done and accomplished, it is hard to see how this will be implemented in any scientifically serious way (although it is quite easy to see how, restricting it to statuses relevant to progressive activist views of reparative justice and who is in protected v. unprotected categories, it could be implemented briefly).”

So why am I doing this? I recently got a paper titled “Diversity is Diverse: Social Justice Reparations and Science” accepted for publication. It started as a critical response to this paper, which, among other things, calls for researchers to include positionality statements when they publish scientific works in psychology. I decided to accommodate this request, much like I accommodated the rise of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion statements here.

My Positionality Statement

I identify as an amateur tennis player. I do realize, dear social justice activists, that this is not what you mean. But you do not get to write my positionality statement. Tennis absolutely has influenced my outlook on life, social science, and teaching.

I had two streaks of receiving at least one trophy a year from 1984-1996, then had a slew of injuries that lasted years, and then had another streak from 2005-2011. I have won tournaments, played on teams that won their division and then won playoffs; and I have not only captained teams, I captained teams into playoffs.

But that is not the best. The best was this one trophy

My adult daughter Kayla, who has disabilities sufficiently serious to be eligible for the Special Olympics, and I, won a mixed doubles tournament that was open to anyone, not just people with disabilities. In the finals, we split sets, then went to a 10 point tiebreaker. I immediately started to choke and before I blinked, we were down 3-0. We battled to down 5-3, and I had an easy shot — which I crushed right into the net. Instead of down 5-4 we were down 6-3. We battled and battled though, taking the lead 8-7 and the next point. At 9-7, I got the exact same type of ball I had “crushed” into the net to go down 6-3, but this time, redemption! I just went for a good-but-not-great shot, hit it, and they did not return it. In dramatic fashion, we came back from 6-3 down, to win 10-7. 2010 Mixed Champs.

In 2018 and 2022, I spent weeks with her, including two special tennis-oriented trips, to sharpen her game in preparation for the Special Olympics. Here she is on her way to winning gold at the 2022 Special Olympics.

Tennis and Academia

Tennis has definitely influenced how I view academic social psychology. In tennis, success has an objective standard. When you hit the ball, it either lands in or it lands out (and you lose the point). The exact same rules apply for your opponent. No one gets special treatment. You either outscore your opponent and win, or your opponent outscores you and you lose. People care quite a lot about applying the rules fairly but not at all about equality of outcome. There may be a grand message in that which goes well beyond tennis.

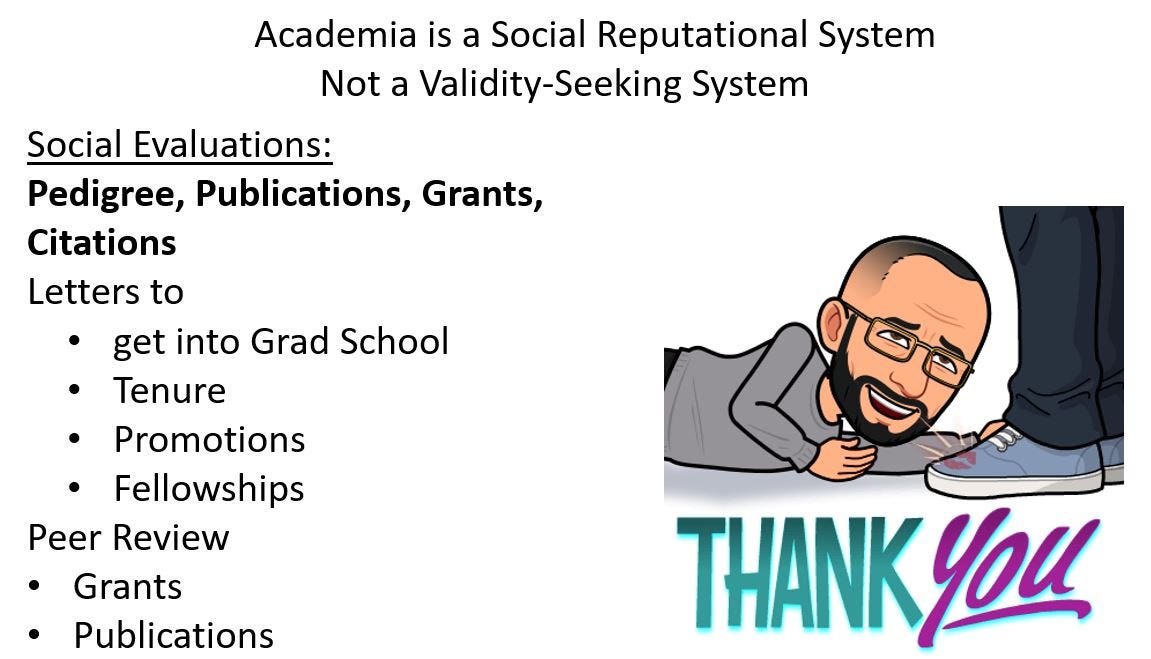

Academic social psychology does not have comparably clear objective standards for success or truth. Success is determined by others’ evaluations of you, not by whether you are right and they are wrong (the approximate scientific parallel to winning and losing). Publish or perish, right? How do you publish? You write a piece of scholarship, and submit it to a journal. The reviewers and editor either like it or they don’t. Others’ evaluations. How do you get a job? In large part, by having great letters of recommendation by famous people willing to say great things about you. Others’ evaluations. How do you get tenure? The same subjective evaluation system plus, at research-oriented universities, grants. How do you get grants? Grant committees say your work sounds great. Others’ evaluations.

Contra tennis, you can succeed in academia no matter how many times you hit the ball and it lands outside the court, as long as you are great at getting other people to say you are great:

I once played on a tennis team where the captain was enamored of players who hit the ball hard. I rarely hit it hard; I had a quirky game of lots of spin and even an underhanded serve; I hit with consistency and placement; and, in those days, I was fit as all Hell, and could often outlast even a somewhat superior opponent (if I could keep it close enough to tire him out). So, come playoff time, the captain hardly played me. I never played for the guy again, but, the next year, I did play in a singles tennis tournament where both he and several of his favs also entered. In one of the most delicious acts of vindication in my life, I won the tournament by beating the guy who beat all of Captain’s Favs. The full story is here,

Tennis teaches the stark difference between looking good and being good. The parallel to scholarship is, I hope, clear. Great writing, fancy statistics, an esoteric polysyllabic vocabulary may make you look good, but they do not necessarily mean your research is sound or your conclusions are true. In tennis, you have skin in the game — your decisions matter. In academia, you have no skin in the game of whether your results are actually true or not; the only skin you have in the game is whether you can get it published. And “published” and “true” are two very different things.

You can have a truly wonderful career, as long as you publish a lot. If you make a big splash, you will get grants, awards, promotions. If it turns out that, 25 or 30 years later, no one can replicate your work, or the claims based on your work are mostly unjustified? Well, you have already had a great career.

Tennis, The (In)Validity of the Peer Reviewed Literature, and Teaching

I once taught this as a hypothetical example to undergrads of how selective reporting of results can produce a “scientific” literature that is unhinged from reality. This table shows data I made up about the success of Jussim’s Amazing Tennis Serve Lessons (this does not exist either, its all a hypothetical to illustrate a point). In this example, 4 samples of people are randomly assigned to either my amazing lesson or a control. Results are pretty mixed with maybe a slight overall benefit from my lessons.

But because the results are inconsistent, I can’t get this published. Journal reviewers loovve nice clean results and hate messy and inconsistent ones (even though social life is often messy and inconsistent). What to do? Pretty it up! Just don’t report Samples 3 and 4, and now it looks beautiful! The journals love such beautiful results, so Samples 1 and 2 make it into a peer reviewed publication! I published and have temporarily avoided perishing! (No one needs ever know about Samples 3 and 4). Lord I must be an extraordinary tennis serve teacher! What? Are you skeptical? Are you some sort of anti-intellectual science denialist? Hey, its peer reviewed!

Ok, now you can’t make this up. Later in the day, after I taught this the first time, a real world example that looks a lot like this was accepted for publication! Put differently, nine, yes, count’ em, nine large sample size failures to replicate of an amazing, dramatic, counterintuitive pair of small studies from the 1980s was published. The original reported two studies, each with itsy bitsy sample sizes of 12-14 per condition, and “found” that transient moods influenced people’s judgments of their life satisfaction. This amazing! Wow! paper was, in 2018 (when I taught it) cited over 5400 times (most papers are mostly ignored; a paper with over 100 citations is pretty good, and over 1000 is very “important”), 5400 attests to how important, how amazing this paper was judged to be.

Is it true? Hey, its an experiment! Its peer reviewed! Iiiiittttttssssss science! Are you expressing doubt? Are you some sort of flat earther? And yet, the paper (Yap et al, 2017), with 9 separate replication attempts, totalling over 2000 participants produced the following negligible effect:

Say it ain’t so, Joe! You mean no one should believe that amazing Wow! effect?

Of course, we cannot know that selective reporting is how the original papers got published. However, selective reporting was common practice in social psychology until around 2011, when this paper scandalized the field by showing, with real data, that, via selective reporting, they could “prove” that listening to the Beatles reduced people’s age (p<.05). Although we can never know that selective reporting was involved, how similar the pattern of the original plus failed replications was to my (maybe silly) tennis example is quite striking. The “published” samples 1 and 2 (tennis) look (in effect sizes) a lot like Schwarz & Clore; the “excluded” samples 3 and 4 (tennis) look a lot like the Yap et al replications.

More in the Land of You Can’t Make This Up:

As of this writing, the Yap et al (2017) mostly failed replications have been cited a total of 66 times. The itsy bitsy sample size original paper has been cited over 2800 times since 2018. 2700+ papers cite the original Schwarz & Clore paper without even acknowledging the existence of the Yap et al (mostly) failed replications. Next time you see someone grandstanding about psychological science being self-correcting, remind them of this. Or just burst out laughing.

Skepticism: My Fundamental “Position” Regarding Social Science

My default positions are:

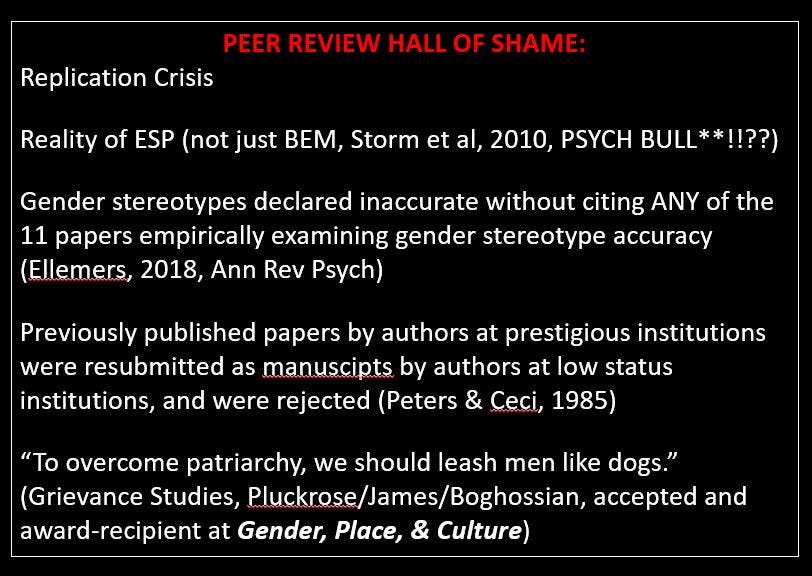

Not to believe anything published in social science without compelling reasons.

This goes double for anything that affirms leftwing worldviews, not because the left is any more biased than the right, but because the leftwing monoculture in most of the social sciences has short-circuited skeptical vetting writ large. The unjustified but nearly monomaniacal focus on replication as the ultimate arbiter for truth claims notwithstanding, the worst manifestations of this are discrimination against individuals, unjustified conclusions (even when based on replicable findings) and the canonization (widespread acceptance as true) of those unjustified conclusions (go here, here, here, or here for more details).

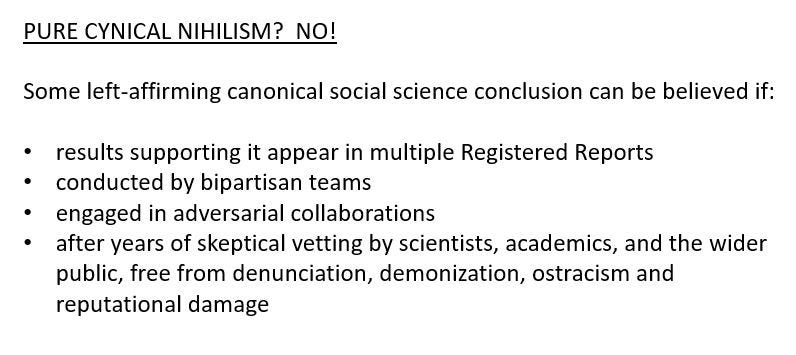

I am, however, a skeptic, not a cynic, even though it is indeed tempting (Nietszche, monsters, abysses and all that).

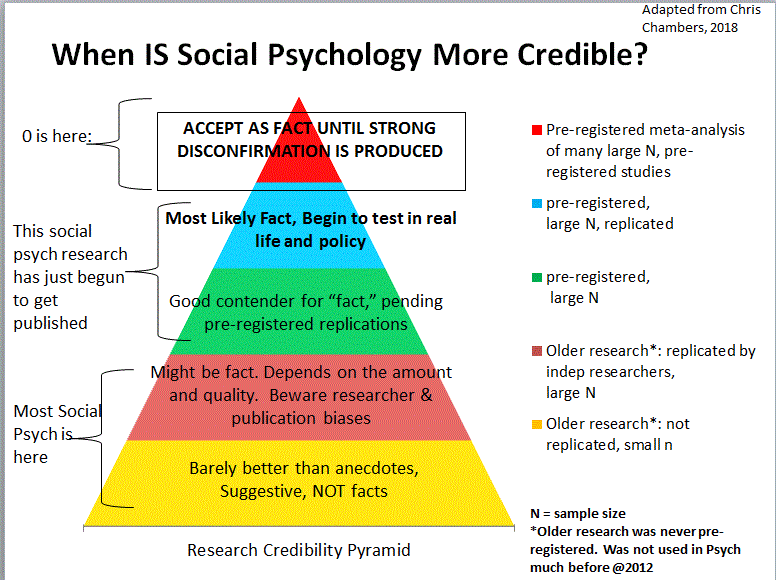

Here is a general way I can be persuaded that social science (and not just social psych as indicated in this pyramid) has produced something that is actually true:

I can even be persuaded that left-affirming results produced by social science are actually true:

Two things: There are actually other ways I can be persuaded, but this essay is already too long; and the social sciences rarely meet either the standards displayed above or my other standards. Not never. Rarely.

Positionality, Are We There Yet?

I mean, if you want to know more about various things in my background that could lead to bias, you might want to read my bio page at Rutgers. It includes things like:

I was born in 1955 in the slums of East New York Brooklyn, where I lived until I was 5. My family then had the “privilege” of moving into a Brooklyn public housing project, where we lived till I was 12. This was a step up from our prior place.

A year later, shortly after moving to Levittown, Long Island, my mother died after a long battle with cancer, and my father fell apart, leaving us alone for days at a time, neglecting our apartment and his two kids. Forced into self-reliance at age 13, I developed a fierce independence and little respect for authorities. In high school I purposely made life miserable for my teachers, so that one of the great ironies of my life is that I eventually became a professor. The way this echoes with my modern skeptical stances via academia is … amusing.

My Rutgers bio only goes through 2016, so here are a few things not there:

From 2018-2022 I chaired the Rutgers Psych Department, through floods (one of our buldings), plague, (fiscal) famine, and Great Gnashing of Teeth. I have, at three points in my life been an actual political activist (contra that moral-political grandstanding you see on social media, if you engage in actual political activism, you need to win people over to supporting your efforts):

From 1970-1973, I was an anti-Vietnam War activist. This included not merely protests, but working for anti-war incumbent Congressional candidate Allard Lowenstein, who got jerrymandered out of his original district, and who lost.

In 1995-1996, I created and led a community group to pass public school budgets and a referendum to build a new school. NJ in the 90’s was swept by No Tax Hike fever, and my town (Franklin) had voted down 5 consecutive school budgets and things had gotten bad. We conducted both a (local) media blitz and a get-out-the-vote campaign. We passed consecutive budgets and got the funding passed to build the new school.

In 2017, I organized a small Indivisible group. At that time, Trump had recently been elected, and Republicans held both the House and the Senate. One of their first initiatives was to attempt to repeal Obamacare. My town was a contested district and had Republican Leonard Lance as its representative. We worked our buns off (and were only a small part of a much larger effort) off to get Lance to vote against his Party and against the repeal. He did.

Also, in this time, the gods delivered to me three grandchildren, currently ages 6, 5 and 3 who I love spending time with. Already been showing the six year old the joys of tennis…

I am Jewish, not “White.” Secular, but Jewish. Europeans hounded my ancestors on and off for 2000 years. History is history, and I have nothing but lovely experiences when visiting Europe and it would be ridiculous of me to resent modern Europeans for the sins of their ancestors. Furthermore, just about every peoples on Earth have committed horrors and atrocities. If I hated Europe, I’d also have to hate pretty much the rest of humanity (hmmmm, wait….?). The legacy of Europe includes The Enlightenment, science, and liberal democracy huge boons to the world. Nonetheless, putting it all together, I do not identify as White. My immediate ancestors came from Russia and Poland, but Jews were kept apart for centuries there and were never fully and permanently accepted into either society. Also, Jews did not originate in Europe; we originated in Asia.

Last, for you Social Justicey types, this is so delicious. My skin tone from May through October is quite dark. Most of the year, it is considerably darker than that of all my Mexican and Cuban relatives. Nonetheless, my lived experience does not include, e.g., being harassed by cops or security more in the summer than in the winter (this does not deny the reality of those who have had those experiences, I am just describing mine).

I have had three experiences, however, that might have involved some degree of Islamophobia. Yes, I know, I am Jewish, but hear me out: 1. I was legally night-fishing (with a bright Coleman lantern) with my kids in October 2001 and someone called the cops; 2. we were detained at the Canadian border for hours and hours trying to re-enter the U.S. in December 2001 when we lacked the right ID for our kids; and 3. the only time I was ever treated rudely by players on a tennis court when their time was just about up and our time was to begin was when I was wearing a keffiyeh (which are wonderful protections from the sun in high summer).1 I don’t have a picture of that, but this was taken in Egypt (where I got it on this successful tomb-raid):

As you can see, I had serious positionality problems on this hike in Colorado:

However, the next year, on our second attempt, I had some of the best positionality in my life:

Footnote

Yes yes yes, there are alternative explanations for all 3 of my Islamophobia examples. People were on edge after the 9/11 attacks, so night fishing may have just seemed unusual and scary to the suburbanites nearby. “See something, say something!” Ugh. On the border stop and delays, we really were missing ID, the border folks were just doing their job (but it was still ridiculous to take hours, it was our kids who lacked ID; just as removing shoes at American airport security is still ridiculous). Remember, Islamophobia has two related meanings: prejudice and fear. Both experiences did seem to reflect an element of fear. And the tennis? I mean, maybe the woman who was unusually rude to me was just an arse. Or having a bad day. Or maybe my letting her know five minutes before it was our time to take the court (clay, which meant they had to take their time to smooth it out before we took it) that we were coming was experienced as me being difficult. Maybe maybe maybe. And maybe not.

This is awesome Lee. Thanks for sharing.

This is a great piece, Lee, I enjoyed every word of it. But here's a shorter version.

Social Science is not science. It's scientism. Social Science can never establish causation, only correlation. Social Science cannot produce anything that even remotely resembles Newton's Laws of Motion - which Einstein showed were not "true" but they remain damned useful to this day. The replication problem in Social Science will never be solved because you can't step into the same river twice. The entire edifice of Social Science is built on false premises, perpetuated by a corrupt academic system joined at the hip with a corrupt publishing system. Other than that, how was the play Mrs. Lincoln? :)