“Focus like a laser on merit!”

My Interview with The German Skeptics

I was recently interviewed by folks over at Skeptiker, a German magazine for and by those with … wait for it … ready? a generally skeptical (though not cynical) demeanor towards all sorts of claims, including those common in social science (thus my interview). They are a sort of German analog of Michael Shermer’s Skeptic Magazine. The interview is presented below in full. My interviewers fully referenced it (references at end) but I have added one reference, some additional links, some parenthetical commentary for missing details I thought relevant and an occasional image that does not appear in the original article. Nothing else has been changed.

Psychologist Timur Sevincer (TS) and philosopher Nikil Mukerji (NM) of GWUP spoke with Lee Jussim (LJ) about bias, stereotypes, and how skeptics should communicate with the public.

TS: As skeptics, we care about pseudoscience, but also about exaggerated or plainly false claims. Which social-science findings are misrepresented the most, be it in academia or in public?

LJ: There are many. One standard narrative is that women face pervasive barriers, especially in STEM. An amazing 2023 paper(1) by a large team complicates that story. The team conducted a meta-analysis (a study that statistically combines results from multiple studies) on decades of audit studies. Audit studies are field experiments that send companies identical fake male and female applications for real jobs to see who gets callbacks for an interview. This is the gold standard in research on hiring discrimination. In earlier decades, there were consistent anti-female biases. By around 2009, these effects had faded or even slightly reversed, with small anti-male effects appearing in female-typical jobs, such as nursing, and no bias in most other fields.

The team also asked people—including scholars—to predict whether the meta-analysis would find biases against men, women, or no bias. Lay people and academics overwhelmingly predicted biases against women. Academics did somewhat better than laypeople, but only slightly.

It gets better: Academics were divided into people with and without gender expertise. Having expertise was operationalized as having at least one paper published with the terms’ gender’ or ‘sex’ in the title or abstract. These experts did not perform differently from other academics. It was a test of how they understood 40 years of literature. [my additional commentary: a test they failed].

TS: When I present that finding to my students, who are generally open-minded, curious, and clever, I often get pushback at first—some seem even to assume I’m pushing a ‘right-wing narrative’. After the initial surprise, however, it’s eye-opening for many, including many women. Why hasn’t the newer evidence spread more widely yet?

LJ: That’s a question about cultural diffusion. I have some hope that if you keep hammering away at the truth as revealed by the strongest evidence, it will change minds. But I wouldn’t bet my life on it.

TS: Let’s talk about the Implicit Association Test (IAT) that supposedly measures unconscious prejudice, and is probably the most widely used measure of such prejudice. What’s your core critique, and how is the IAT miscommunicated?

LJ: In brief, the IAT is a reaction-time task that infers the strength of automatic associations in memory, not a direct readout of hidden prejudice. Early claims framed it as detecting “unconscious bias” in most people, such that it would reveal that 80 or 90% of Americans were unconsciously racist. Two problems. First, it is not tapping into anything unconscious: When researchers explained the test and asked people to predict their own scores, the predictions were remarkably accurate, which undermines the idea that the test reveals wholly unconscious biases. There is almost nothing unconscious about what is measured by the IAT. Second, the IAT does not measure bias. It measures at best the strength of association between concepts in memory. People will associate the French with wine. In what universe is that association a bias? And there are technical criticisms regarding how well it even measures the strength of associations in memory. Also, associations in memory are not the same thing as prejudice or discriminatory behavior. You can temporarily shift IAT scores; translating that into behavior is another matter(2). [commentary: it is not merely “another matter” — the reference here is to research finding that changing IAT scores had no effect on discriminatory behavior].

TS: I’ve seen headlines implying implicit bias literally kills Black patients (3, 4) through microaggressions (brief, often unintentional slights toward marginalized groups), causing serious health harms, and calls for anti-bias training across healthcare. What are your thoughts on that?

LJ: There was a study(5) reporting a pattern whereby black babies were more likely to die under the care of a white doctor. A reanalysis by other researchers(6 7) showed that the statistical pattern was explained by the fact that white doctors disproportionately treated low-birth-weight Black infants. Low birth weight is a strong mortality risk. When that was accounted for, the effect disappeared.

TS: Even students asked me about the study.

LJ: Yes. It has captured the public imagination, despite the findings being debunked. Moreover, implicit bias probably appeals to psychologists and laypeople because these concepts address subtle, unconscious drivers of human behavior. Many psychologists and social scientists seem to think that if everything is more or less conscious, it is uninteresting. However, some of the most effective measures of prejudice are the direct and blunt ones.

TS: There are reasons to be skeptical about self-report measures. For example, people’s ability for introspection does seem to be limited.

LJ: Almost anything in social science should be treated skeptically – with few exceptions. Only when findings survive, despite having been treated skeptically over a long time, do they become credible. We wrote a paper on academic misinformation(8), which goes through case after case of academics promoting nonsense, like the idea that the IAT is unconscious.

NM: Universities offer workshops aimed at reducing bias, for example, in hiring. They claim their interventions are based on empirical findings, citing studies. Offers from the private sector look like pseudoscience. We found workshops involving unconscious bias trainings that costs between $1.000 and $5.000 (9, 10, 11).

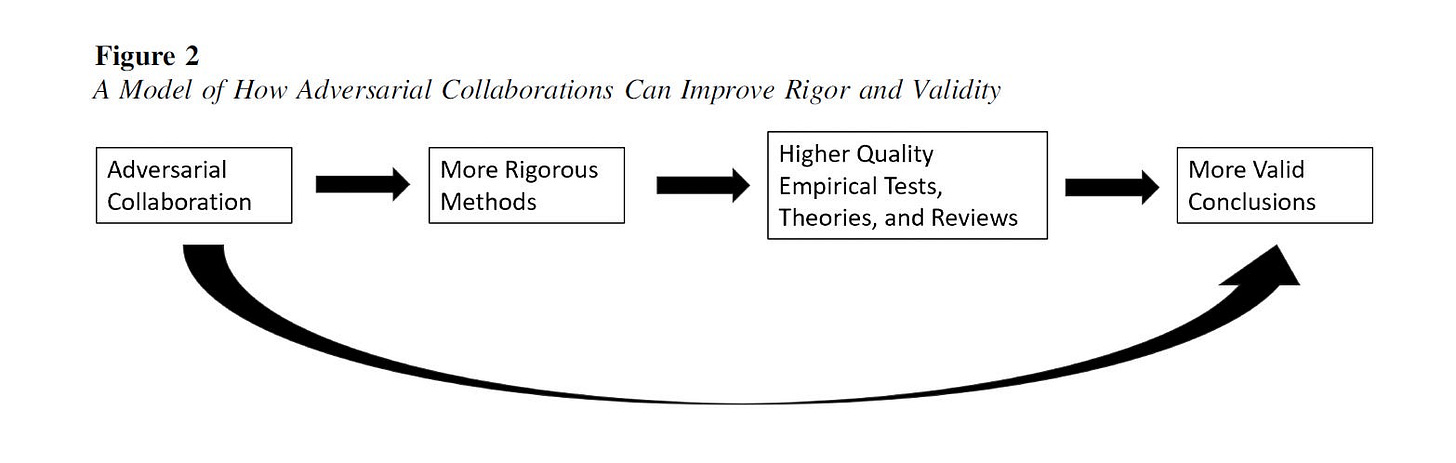

LJ: With an adversarial collaboration team, we have just published a paper that evaluated the effectiveness of such DEI programmes (12)— diversity, equity, and inclusion programmes, which often, though not always, have a training component. Part of our review focused on the effectiveness of various kinds of anti-bias training. We found there’s no evidence. And many of the anti-bias trainings haven’t been evaluated. It seems people are presenting their opinions as if they have a scientific basis. Now they can cite articles saying diversity is wonderful, and therefore, we need to have this training. Yes, you can cherry-pick articles about the wonders of diversity, but then you’re systematically ignoring the ones where diversity is ineffective or counterproductive. But even if you stipulate that diversity is wonderful, that doesn’t mean your particular implementation is doing more good than harm. Evidence for that mostly does not exist. One of the few examples where systematic evidence exists on training effectiveness is the effect of implicit bias training on subsequent discriminatory behavior. It was done by an advocate of implicit bias who has conducted extensive research on the topic. I’m sure they wanted it to have a positive effect. It was a meta-analysis on interventions to change implicit bias(13). Actually, they did change IAT scores, but there was no downstream effect on behaviour.

TS: Can you be too aware of biases? Can there be drawbacks to this focus on biases?

LJ: Well, if you evaluate any intervention, you should not simply evaluate whether it accomplishes its intended goal. You should also assess unintended negative side effects. Or even intended negative side effects. And that’s almost never done.

I think it’s highly likely that overemphasis on bias can lead to an overreaction. You can produce a reverse bias. For most of the last 30 years, academics have been writing as if that doesn’t exist. The Students for Fair Admissions cases at the U.S. Supreme Court, for example, revealed that Harvard and UNC’s, and probably many other institutions’, race-conscious admissions policies violated equal-protection law. If you were White or Asian, you needed 100 to 300 points higher on your SAT to get admitted into Harvard.

If you make people hypersensitive to their biases, you’re likely to get an overreaction in this direction. That leads to us an empirical question: Can these trainings produce that sort of overreaction? I guess they can. There’s currently no scientific evidence that I am aware of, but it’s a concern that should be evaluated.

NM: Could there also be consequences for everyday life? Could you start seeing prejudice and biases everywhere, even when they are not there?

LJ: One of my top 10 Substacks is titled “Is everything problematic?” written at the height of the social justice movement after the George Floyd murder.

There were like 10 zillion things accused of being racist or sexist. Sometimes they’re academic articles, sometimes they’re mainstream media articles written by academics, and sometimes they’re just mainstream. The articles identify everything as racist. Golf is racist. Bedrooms are racist, lawns are racist, and jogging is racist. One example [that I made up to illustrate the point that anything can be cast as racist] is dog walking. Dog walking is racist because how dare you take a dog to a wonderful day outdoors when, in fact, black men are suffering in prison for crimes they didn’t commit. You can do this with anything, absolutely anything.

TS: Let’s turn to stereotypes. When I show my students data that women tend to prefer people-oriented and men things-oriented jobs(14), some reject them because they view it as perpetuating stereotypes.

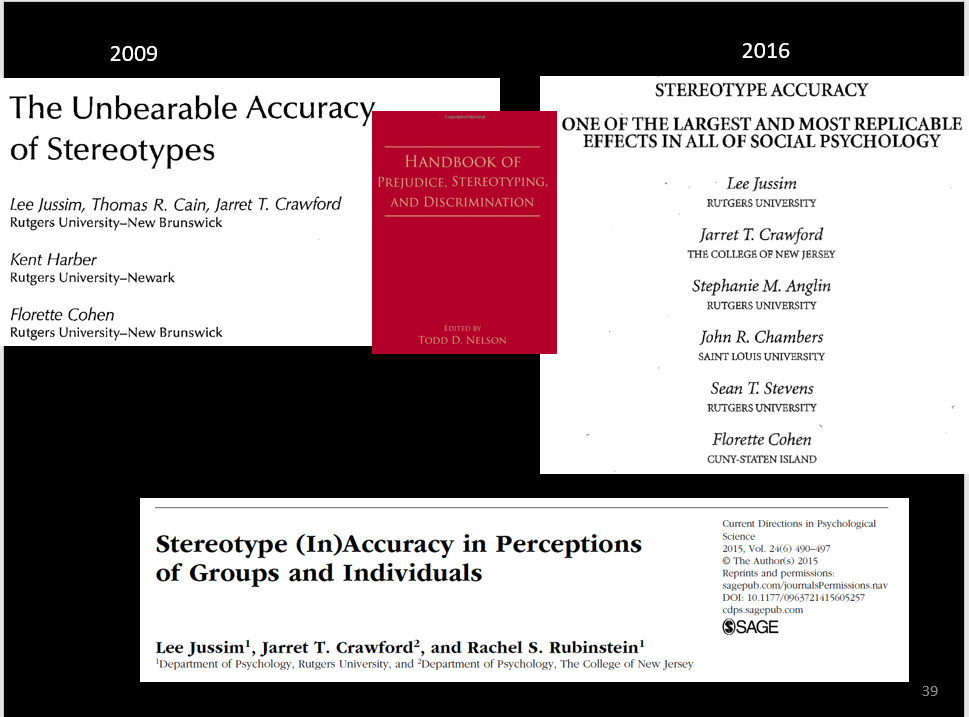

LJ: If you define stereotypes as inaccurate, two things follow. First, at least from a scientific standpoint, it requires you to have evidence that the belief is wrong. Because if you don’t have evidence that the belief is wrong, then you can’t call it a stereotype. However, what often happens is the reverse: people take a claim about groups, such as the notion that women prefer people-oriented jobs and men prefer things-oriented jobs, and they describe it as a stereotype, implicitly importing the assumption that it’s wrong without providing any evidence. Also, saying all beliefs about groups are stereotypes and inaccurate is incoherent. This would mean that two groups cannot be similar or different, because both views would be stereotypes. But one must be correct. In practice, many broad group beliefs are partly accurate, partly exaggerated, and highly context-dependent(15, 16).

NM: So, what is the best way to deal with stereotypes in practice?

LJ: I’m not offering a silver bullet. However, in my view, the single best answer is to focus like a laser on merit and to gather individualized information. You may have biases, but if your attention is focused on evaluating who is the best student to admit or who is the best person for the job, biases decrease. Two lines of evidence support this. First, the best antidote is to focus on the person’s concrete track record—their individual information. When decision-makers attend to specific, diagnostic individual data, the effects of stereotypes shrink. For example, I may have some horrible beliefs about your group. But if I’m thinking about hiring you, and I look at your record, I may find you have this great research record. I don’t really give a damn that you belong to all these groups I don’t like. What matters is whether you will contribute to my enterprise. Now, the biases are more likely to fall by the wayside. There is overwhelming evidence that people do rely on such individuating information if it is available.

Second, a meta-analysis(17) was conducted a couple of years ago on what constellation of beliefs predicts the lowest amount of discrimination. There were three sets of beliefs: multicultural beliefs, colorblind beliefs, and a belief in merit. The strongest negative relationship with discrimination was found in people who believed in merit. The more strongly people believed in merit, the less they engaged in discrimination.

So, in a nutshell, aim laser-like at merit—clear, job-relevant criteria—and actually use individualized evidence. It’s not a magic wand, but it’s the most reliable way to suppress bias in practice.

TS: Would you say that the harmful effects of stereotypes in everyday life are overblown?

LJ: In some contexts, you’ll have governments or institutions promoting really pernicious beliefs in the name of propaganda. That’s a different situation. When we’re discussing interpersonal situations in the U.S., I think they are often overblown. There is good evidence of people’s stereotypes about others’ stereotypes. If you ask people what other people believe, they will think people have more extreme beliefs about, say, men and women, than they really have(18, [note: I added 18a which documents this clearly and empirically). So yes, I do think the harmful effects of stereotypes are overblown.

NM: Let’s turn to science communication, which is an issue near and dear to our hearts as skeptics. Some people worry that emphasizing uncertainty and critique erodes trust in science.

LJ: A couple of things. First, science is less credible when fields are skewed in one political direction because you don’t have as many skeptical checks on. In academia, at least in the U.S. and probably also in Germany, people are overwhelmingly on the left, particularly in the social sciences and humanities(19), as well as to a lesser extent in the biomedical sciences and STEM fields. Because there are fewer skeptical checks on politicised topics, it’s reasonable for people, especially people on the right, to be skeptical of some of what emerges from academia. The solution is to attempt to restore some political balance. But I don’t know how to do that. I’m not arguing for affirmative action for conservatives, that we stop hiring liberals until say 30% of academia is conservative. That’s a silly idea. Nonetheless, the fields would be better if there were more conservatives.

Also, how does a scientific claim become credible? There are probably many answers to that, but my shortest version is that it takes about 20-30 years of research before we can be reasonably sure that a finding holds up. One way to heighten credibility on either politicised topics or even just non-political theoretical controversies is the adversarial-collaboration approach(20): set methods and outcomes in advance with your intellectual opponents and publish a joint assessment – be it on a review paper or an empirical question.

TS: Returning to the topic of gender bias in academia, a recent adversarial collaboration(21) on this issue found no bias in many domains. It also found barriers for women in some domains, and bias against males in hiring, which raises questions about why many implicit-bias training still targets anti-female bias when actual hiring outcomes can cut the other way(22).

LJ: Exactly. However, barriers and biases are not the same thing. A bias is when a selection committee decides between a female and male candidate and gives the nod to the weaker candidate because of their gender. A barrier is different. For instance, universities give people time off for having a baby. But men and women use that time differently. Men tend to be more productive during this period because they are doing less childcare than their wives. This is a barrier – an obstacle to women’s advancement within academia. It’s not a bias. When it comes to biases, some fields exhibit pro-female preferences, while others show pro-male preferences, and many contexts reveal no bias at all. It’s not a one-story world.

NM: Isn’t the fear that when you tell the public that we either don’t know or that there is a controversy in science, that this could decrease trust in science? What is your take?

LJ: If we are uncertain about something, the public deserves to know that, and we should be forthright about it and more accurate in our proclamations. We must be both earnest and accurate. If we go around saying we’re sure about something when we really don’t deserve it, that’s just going to shoot us in the foot, and they’re not going to believe us when they should believe us. On the one hand, we need to admit that we don’t really know, but on the other hand, there are things we do know.

However, much of what matters is politics and policy. If scientists are uncertain, then the policy implications are unclear. It is unreasonable to rely on unclear science to inform policy decisions. It may not even be reasonable to rely on science where it is clear, because policy involves all sorts of considerations other than whether some factual claim is true. There are other interests at stake here, and policymakers must weigh all of these factors, not just whether the science is accurate. However, once there is sufficient scientific certainty, science should be one piece of information that informs public discourse and policy-making, even though it need not be determinative of the policy.

NM: The public likes confidence. Activist scholars say “we know” – and that sells. That’s a problem, isn’t it?

LJ: You’re right, people are much more persuaded by somebody who stomps in and confidently declares all sorts of nonsense. It’s as if they know it to be true, and everybody knows. I wish I had an answer. I don’t.

NM: There is another problem that keeps bugging me. The mission of skepticism is twofold. Firstly, we promote critical thinking. We encourage people to apply their own reason and come up with their own conclusions. However, they might draw false inferences and then believe nonscientific nonsense. That seems to conflict with another mission, namely, to communicate solid scientific findings to the to the public and persuade them to believe us. I believe the tension between these two goals has never been thoroughly considered. How would you prioritize those two goals? Is it more important to encourage people to think critically for themselves, or is it more important to teach them what reality is all about?

LJ: I would be uninhibited to communicate the truth as you understand it, including the uncertainty around your understanding of that. I think you can do that regardless of whether you teach critical thinking or not.

NM. Campus activists and DEI bureaucracies have at times used deplatforming, investigations, and funding pressures to silence heterodox voices. Now that President Trump has been reelected, how have these threats to free inquiry shifted, and what does that mean for the future of open debate in academia?

LJ. Trump’s return hasn’t ended campus illiberalism; it’s diversified it. In addition to deplatformings and bureaucratic investigations from within universities, the administration has chilled inquiry from the other direction—defunding most research on DEI, prejudice, and inequality, and seeking to bar federal funding to universities whose DEI programs it deems discriminatory. Broad financial pressure predictably narrows the scope of what scholars dare to study. Add the targeting for deportation of noncitizens allegedly expressing support for Hamas—measures that, legal or not, deter open discussion—and the rapid capitulation of institutions (Politico dubbed it “the Great Grovel”), and you don’t get freer debate; you get bipartisan fear. The remedy is not retaliatory censorship, but viewpoint-neutral, principled protections so research agendas aren’t set by partisan leverage or by those most eager to punish dissent.

NM. You’ve argued that today’s climate of “fear equity” might paradoxically be good for free inquiry in the long run. What makes you think so?

LJ. Shared vulnerability creates the incentives we’ve lacked. When only one side felt exposed, many rationalized censorship as preventing “harm.” Now both left and right can see how weaponized procedures, funding levers, and immigration threats chill inquiry. As Madison put it in Federalist 51, freedom is best secured when “ambition…counteract[s] ambition.” With both camps needing protection for themselves, they have reason to accept rules that protect their opponents as well—namely, clear, viewpoint-neutral speech and academic freedom norms, consistently enforced.

NM. This seems fine in theory. But has this ever worked?

LJ. Yes, it has. The McCarthy-era excesses led to court cases that strengthened free speech. Temporary overreach triggered durable protections. The campus analog is institutional reform: adopt and enforce Chicago/Princeton-style free-speech and academic-freedom statements; bar ideological litmus tests in hiring, promotion, and accreditation; create Offices of Academic Freedom empowered to review DEI units, IRBs, and administrators for rights violations; require content-neutral security and space policies; and protect lawful speech for noncitizen scholars. Law helps—e.g., by prohibiting compelled ideological statements—but culture matters even more: leaders must consistently defend controversial speakers, and faculty senates should censure cancellation campaigns regardless of the target. If fear equity aligns self-interest with principle, we have a real chance to rebuild a robust, viewpoint-neutral environment for open inquiry.

References

1) Schaerer, M., Du Plessis, C., Nguyen, M. H. B., Van Aert, R. C., Tiokhin, L., Lakens, D., ... & Gender Audits Forecasting Collaboration. (2023). On the trajectory of discrimination: A meta-analysis and forecasting survey capturing 44 years of field experiments on gender and hiring decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 179, 104280.

2) Jussim, L. (2022). 12 Reasons to be sceptical of common claims about implicit bias. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/rabble-rouser/202203/12-reasons-be-skeptical-common-claims-about-implicit-bias

3) Williams, M. T. (2023). How implicit bias kills black babies. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/culturally-speaking/202505/how-implict-bias-kills-black-babies

4) Gran-Ruaz, S., Mistry, S., MacInytre, M.M., Strauss, D., Faber, S., & Williams, M. T. (2025). Advancing equity in healthcare systems: Understanding implicit bias and infant mortality. BMC Medical Ethics, (26) 103, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-025-01228-y

5) Greenwood, B. N., Hardeman, R. R., Huang, L., & Sojourner, A. (2020). Physician–patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(35), 21194-21200.

6) Borjas, G. J., & VerBruggen, R. (2024). Physician–patient racial concordance and newborn mortality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(39), e2409264121.

7) Joyce, T. (2024). Do Black doctors save more Black babies? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(39), e2415159121.

8) Jussim, L., Yanovsky, S., Honeycutt, N., Finkelstein, D., & Finkelstein, J. (2025). Academic Misinformation and False Beliefs. In The Psychology of False Beliefs (pp. 171-187). Routledge.

9) Cultural Intelligence Center (2025). Unconscious Bias Train-the-Trainer. Retrieved from: https://culturalq.com/cq-store/certifications/unconscious-bias-train-the-trainer/

10) Haufe Akademie (2025). Diversity Sensibilisierung im beruflichen Kontext. Retrieved from: https://www.haufe-akademie.de/34247

11) Dear Human Services (2025). Diversity Training. Retrieved from: https://dearhuman.de/diversitytraining/

12) Mogilski, J., Jussim, L., Wilson, A., & Love, B. (2025). Defining diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) by the scientific (de) merits of its programming. Theory and Society, 1-14.

13) Forscher, P. S., Lai, C. K., Axt, J. R., Ebersole, C. R., Herman, M., Devine, P. G., & Nosek, B. A. (2019). A meta-analysis of procedures to change implicit measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(3), 522–559. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000160

14) Su, R., Rounds, J., & Armstrong, P. I. (2009). Men and things, women and people: a meta-analysis of sex differences in interests. Psychological Bulletin, 135(6), 859.

15) Eagly, A. H., & Hall, J. A. (2025). The kernel of truth in gender stereotypes: Consider the avocado, not the apple. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 118, 104713.

16) Jussim, L., Cain, T. R., Crawford, J. T., Harber, K., & Cohen, F. (2009). The unbearable accuracy of stereotypes. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (pp. 199–227). Psychology Press.

17) Leslie, L. M., Bono, J. E., Kim, Y. S., & Beaver, G. R. (2020). On melting pots and salad bowls: A meta-analysis of the effects of identity-blind and identity-conscious diversity ideologies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(5), 453.

18) Swim, J. K. (1994). Perceived versus meta-analytic effect sizes: an assessment of the accuracy of gender stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(1), 21-36.

18a) Rettew , D. C. , Billman , D. , & Davis , R. A. ( 1993 ). Inaccurate perceptions of the amount others stereotype: Estimates about stereotypes of one’s own group and other groups. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 14, 121 – 142 .

19) Duarte, J. L., Crawford, J. T., Stern, C., Haidt, J., Jussim, L., & Tetlock, P. E. (2015). Political diversity will improve social psychological science1. Behavioral and brain sciences, 38, e130.

20) Ceci, S. J., Clark, C. J., Jussim, L., & Williams, W. M. (2024). Adversarial collaboration: An undervalued approach in behavioral science. The American psychologist, 10.1037/amp0001391. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001391

21) Ceci, S. J., Kahn, S., & Williams, W. M. (2023). Exploring gender bias in six key domains of academic science: An adversarial collaboration. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 24(1), 15-73.

22) Williams, W. M., & Ceci, S. J. (2015). National hiring experiments reveal 2: 1 faculty preference for women on STEM tenure track. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(17), 5360-5365.

Commenting

Before commenting, please review my commenting guidelines. They will prevent your comments from being deleted. Here are the core ideas:

Don’t attack or insult the author or other commenters.

Stay relevant to the post.

Keep it short.

Do not dominate a comment thread.

Do not mindread, its a loser’s game.

Don’t tell me how to run Unsafe Science or what to post. (Guest essays are welcome and inquiries about doing one should be submitted by email).

Excellent interview. "The remedy is not retaliatory censorship, but viewpoint-neutral, principled protections so research agendas aren’t set by partisan leverage or by those most eager to punish dissent."

This quote about affirmative action for conservatives seems dismissive.

"The solution is to attempt to restore some political balance. But I don’t know how to do that. I’m not arguing for affirmative action for conservatives, that we stop hiring liberals until say 30% of academia is conservative. That’s a silly idea. Nonetheless, the fields would be better if there were more conservatives."

If it is a plainly silly idea then it implies all affirmative action ideas are and were silly.

If there is utility to affirmative action initiatives (at least in the short term) then why would it be silly to apply it to political diversity when it seems clear there are artificial pressures driving a bias/barrier/gap? There is at least as much evidence as any other in vogue diversity metric.