What appears below is my article that was denounced by almost 1400 academics as racist, and contributed to the Perspectives on Psych Science (PoPS) Debacle (go here, here, or here for more info on this). It is one of the articles critical of Roberts et al (2020) that was accepted by former editor of PoPS, Klaus Fiedler, and which contributed to his defenestration at the hands of authorities who caved to the demands of an academic outrage mob.

This article was completed with support from the Institute for Humane Studies under grant number IHS001397. My positionality statement can be found here.

Abstract

Because the term “diversity” has two related but different meanings, what authors mean when they use the term is inherently unclear. In its broad form, it refers to vast variety. In its narrow form, it refers to human demographic categories deemed deserving of special attention by social justice-oriented activists. In this article, I review Hommel’s critique of Roberts et al (2020), which, I suggest, essentially constitutes two claims: 1. that Roberts et al’s (2020) call for diversity in psychological science focuses exclusively on the latter narrow form of diversity and ignores the scientific importance of diversity in the broader sense; and 2. Ignoring diversity in the broader sense is scientifically unjustified. Although Hommel’s critique is mostly justified, this is not because Roberts et al (2020) are wrong to call for greater social justice-oriented demographic diversity in psychology, but because Hommel’s call for the broader form of diversity subsumes that of Roberts’ et al (2020) and has other aspects critical to creating a valid, generalizable, rigorous and inclusive psychological science. In doing so, I also highlight omissions, limitations, and potential downsides to the narrow manner in which psychology and the broader academy are currently implementing diversity, equity, and inclusion.

“Of course, there was the time he sold him a horse, and delivered a mule.”

Tradition, from the Broadway production of Fiddler on the Roof.

The Oxford Languages Dictionary provides two definitions of diversity:

1. The state of being diverse, variety.

2. The practice or quality of including or involving people from a range of different social and ethnic backgrounds and of different genders, sexual orientations, etc.

Inasmuch as “the state of being diverse” is not very helpful for understanding the meaning of “diversity,” I looked up “variety.” The same dictionary defines “variety” as “the quality or state of being different or diverse; the absence of uniformity, sameness, or monotony.” The first definition is clearly the broader of the two and subsumes the second definition. This risks creating confusion about what is being discussed. If someone promises “diversity” interpreted in the broader sense, but delivers “diversity” in the narrower sense, that person is plausibly interpretable as having, metaphorically, sold a horse but delivered a mule.

That, in a nutshell, is Hommel’s critique of Roberts et al (2020) paper on “Racial inequality in Psych Research,” and it hits the bullseye. Diversity, in the broadest sense, which subsumes and therefore includes the narrower sense, is crucial for a valid and credible psychological science. “Diversity” is diverse. Even when restricting the term’s usage to people, the ways in which people can be diverse is vast, including demographics, political, experiential, expertise, and varieties of cognitive styles, beliefs, and values. Restricting the term even more, to focus specifically on psychology, the vastness of diversity is critical for understanding and evaluating the quality and validity of psychological science. The vastness of diversity is relevant to psychology in diverse ways, including but not restricted to: 1. aspects of human psychology that have received scientific attention; 2. the samples of people that have been the subject of empirical investigation; and 3. the researchers themselves. The diversity of researchers themselves is important for both reasons of justice (excluding people from particular backgrounds is an injustice) and science (a science populated by researchers from diverse backgrounds is more likely than one populated by those from a narrow set of backgrounds to study a broader diversity of aspects of human psychology and, possibly, to be more highly motivated to ensure that more diverse samples of people become the subject of psychological science).

Hommel has made three main arguments: 1. Diversity goes so far beyond race (and other marginalized or underrepresented demographics) that, even though from a social justice/activism/reparations standpoint focusing on race and/or other marginalized or underrepresented demographics makes a great deal of sense, scientifically, i.e., from a validity-seeking or truth-seeking perspective, it is not justified; 2. Race may matter for some scientific questions vastly more than others (moderators vs. mechanisms) and Roberts et al (2020) did little to demonstrate fundamental differences in psychological processes based on race for scientific questions; and 3. Agency, aka as “self-selection,” constitutes an alternative to discrimination as an explanation for gaps (i.e., perhaps differences in demographic distributions into various positions at least in part reflects preferences and interests) and that Roberts et al completely failed to acknowledge this as even a possibility.

To evaluate Hommel’s critique, one must first consider Robert et al’s review. It reflects much of what is currently wrong with academia in general and the social sciences including psychology in particular. This does not mean everything in it is factually incorrect or wrong, but it is an almost surreal mixture of ideologically infused anti-racist activism and science. Once upon a time “antiracism” had a simple conventional meaning of “against racism” – but what anti-racism even means now depends on one’s ideological worldview. The conventional form of anti-racism until very recently has been that of Martin Luther King’s invocation to judge people by the content of their character. One can now routinely find arguments to judge people on their individual merits rejected by academics (e.g., a Google Scholar search on “the myth of meritocracy” yielded over 2600 papers). The modern far left version is that racism is deeply infused into every aspect of America’s and indeed most western democracies’ social, cultural, and political life and that King’s invocation seems quaintly naïve.

The Perils of a Politicized Science: A Case Study

This is not the place to conduct a thorough critique of the Roberts et al (2020) paper. Nonetheless, in order to evaluate Hommel’s critique it may be useful to point out some of the more obvious flaws of the Roberts et al (2020) article. First, a general principle: activism-infused scholarship can often be detected by its flagrant disregard for truth and/or its tendency to highlight facts that actually are true only if they fit the activist narrative, and to systematically ignore narrative-contesting facts. It has been argued that, because activism prioritizes seeking power to implement political goals, and anything goes when seeking power, activism inherently compromises truth (Haider, 2022). Although political agendas have a long and ugly history of compromising the natural and social sciences (Brothers, Bennett & Cho, 2021; Honeycutt & Jussim, 2020, in press; Krylov, 2021; Martin, 2015; Smith, 2014), whether they inherently do so is beyond the scope of the present paper. Nor is this the place to navigate the nuances of “everything is political” as applied to psychological scholarship, although it is worth stating that, even if everything is political in some senses, this does not liberate scholars to engage in distortions or omissions of inconvenient evidence.

I present two examples of unjustified or inadequately justified claims from the Roberts et al (2020) paper and one from Roberts & Rizzo (2020). It starts with Roberts et al’s (2020) very first sentence. “It is well documented that race plays a critical role in how people think, develop, and navigate the social world (Roberts & Rizzo, 2020).” Roberts & Rizzo (2020) is about racism. It is not about the role race plays in any of the myriad of ways that people think, develop or navigate the social world irrelevant to racism. Is there a shred of evidence that “racism plays a critical role in how people think” about anything other than race, racism, power, status, and hierarchies? There may well be, but Roberts & Rizzo (2020) did not present it.

Second, Roberts & Rizzo (2020) is itself a deeply flawed analysis. While claiming (p. 6) that “…white supremacy is deeply and intricately woven into the fabric of U.S. society…” they systematically overlook evidence that is inconsistent with this conclusion. For example, after reviewing evidence on how White people disproportionately hold many positions of status and power, they failed to include the evidence showing that Asian Americans hold more college and professional degrees than any other U.S. Census demographic group (USA Census, 2022a), and also have the highest family incomes (it may be worth pointing out that “Asian Americans” includes many groups, including Americans of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Indian, Pakistani and Filipino descent, as well as many others). Similarly problematic for their perspective has been how many African immigrants’ education and income exceeds that of White people in the U.S. (USA Census, 2022b). Also excluded from their review are studies showing that, controlling for educational attainment, Black women actually earn more than White women (Fryar, 2011), and “high school completion and college attendance rates are uniformly higher for black women than for white men across the parental income distribution” (Chetty et al, 2019, p. 744). Although this review is not the place to present a richly nuanced review of the extent to which this and other similar evidence challenges claims of pervasive White supremacy (though see Reilly, 2021, for a brief readable review that is far more extensive than the present article), it concretely demonstrates how Roberts & Rizzo (2020) presented facts and studies selectively.

Third, Roberts et al (2020) bemoan the fact that 83% of editors in several mainstream psychology journals were White between 1974 and 2018. Census data (USAFacts, 2022) shows that percent White in the U.S. in the 1970s was nearly 90% and it did not dip below 83% until the 1995. As Hommel correctly pointed out, the U.S. is not the only country that contributes to psychological science in the English language journals they surveyed. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the population of other countries that do so. The Black proportion of the population has been (and continues to be) historically even lower in other English-speaking countries (relevant to journal editors), such as Canada (3.5% in 2016; Statistics Canada, 2019) and the UK (3%, Index Mundi, 2022). Of course, scholars where English is not the primary language also contribute to the English language psychological literature. Hommel reported that the overall European percent Black is 1.3%.

Thus, with respect to a scientific analysis of “inclusion” and “representation,” at least with respect to psychology editors in the sample that Roberts et al (2020) studied, the average percent White editors from 1974-2018 is consistent with a level of representation that approximates or (depending on one’s benchmark) is less than that of the underlying population. As such, it debunks rather than confirms the notion that there is some sort of unjust gap in the demographics of the psychology editors they found crying for special remediation policies. But that assumes that “inclusion” means “no evidence of exclusion”; it also assumes that “representation” refers to the statistical representation in proportion to some standard (whether representation in the population or some other standard, such as proportion of PhDs is appropriate, is beyond the scope of this article). However, if one takes a political activist lens, one demanding reparative social justice rather than a scientific one, to atone for historical discrimination, “inclusion” must be satisfied by biases favoring those historically marginalized groups. Similarly, when using that same political activist lens, “representation” does not mean statistical representation in proportion to the population, it means overrepresentation (in order to provide reparations for past bias). Inclusion and representation, too, then, can constitute (political social justice) mules delivered when (scientific) horses were promised. It would be easy to present more such examples because there are so many in the Roberts et al (2020) and Roberts & Rizzo (2020) articles, but it would get tedious, so now I turn to an evaluation of whether Hommel’s criticisms are valid.

From a political activist perspective, Hommel’s criticisms are entirely wrongheaded. All criticisms of arguments forwarded to advance a political agenda are wrongheaded to the extent that they are potential obstacles to advancing that agenda. Politics is a no-holds barred game; almost anything goes, including lying, distorting, and promoting propaganda to justify and advance one’s preferred policies and outcomes. The “winner” is determined not by truth or demonstrable improvements to human well-being, but only by who gains power and gets to implement their preferred policies. In an excellent analysis of propaganda in science, Gambrill & Reimann (2011) developed an index for reviewers to use when evaluating papers submitted for publication, and which includes these items (and many more like them, rephrased here as questions).

Did the paper acknowledge that the nature of the problem addressed is in dispute?

Did the paper present only one view of the problem?

Did the paper present their view as established (when it is not)?

Are possible harms of the view promoted described?

Are controversies regarding prevalence noted?

I will leave it to readers to decide the answers to these questions regarding the Roberts et al (2020) and Roberts & Rizzo (2020) papers for themselves.

Hommel’s Scientific Critique

I now turn to Hommel’s specific criticisms on scientific grounds. They are mostly well-justified. His first was that Roberts et al (2020) ignored all forms of diversity beyond the demographic categories of special concern to social justice-oriented academics. This is clearly true. Nonetheless, just as a mule is horse-like (indeed, genetically, it is half horse), Roberts et al make some scientifically valid and important points. For example, they are on solid scientific ground when they call for greater transparency (e.g., providing info on the demographics of samples) and acknowledgements of limitations. They are also on sound scientific grounds to argue that, if one only studies White people, one cannot possibly know the same phenomenon would hold among non-White people. Of course, scientifically, exactly as Hommel implied, one cannot possibly know the same phenomenon would hold across any two identifiable groups unless those groups were studied.

Roberts et al (2020, p. 1302) are probably right when they attribute variation in sample racial identity composition to “...authors of color [being] more invested in communities of color...” Less clear is the scientific justification of their lauding of research that includes massive underrepresentation of White people in their samples (e.g., 19% for developmental psychologists of color). I note here that, even in 2021, when the U.S. is more racially/ethnically diverse than ever, the population is 75% White (including what the Census refers to as Hispanics, who can be of any racial identity) or 59% White (excluding Hispanics; USAFacts, 2022).

Similarly, it is not clear that Roberts et al’s (2020) dim view of the methods used by White social psychologists that produced a 69% overall proportion of White participants is justified. Given that the studies they examined went from the 1970s (when the U.S. was nearly 90% White) through the 2010s, when the U.S. ranged from about 60-75% White (USA Facts, 2022), the samples collected by White social psychologists more closely corresponded to American national demographics than did those of any other combination of field and author demography that Roberts et al (2020) reported. If one includes the racial demographics of the countries in which the research was performed in Robert et al’s (2020) sample of articles, the proportion of White people in the population is likely even higher given the very low levels (about 1%) of Black people (and other people of color) in European samples. Although relatively few psychology publications report truly representative samples, the samples collected by White social psychologists did the best job of the fields Roberts et al (2020) examined with respect to capturing racial demographics that approximate the underlying population demographics during the time period they studied. Scientifically, representativeness is clearly a methodological strength, so why the dim view? From a reparative social justice activist perspective, population demographic representativeness is a liability because it fails to massively overrepresent demographics of color, as Roberts et al (2020) document is the case, e.g., with developmentalists of color.

To be sure, if some psychologists in some fields wish to devote extra effort and attention to samples of color, I have no objection. Special attention to samples of color deserves a place in psychological science. Let’s not pretend, however, that such samples are somehow inherently scientifically more rigorous than ones that more closely approximate the demographics of the underlying population. Scientists who wish to plow their fields with mules should permitted to do so; they should not, however, pretend that those mules are horses or suggest that, unless others give up their horses, they are doing something scientifically suboptimal.

Similarly, when Roberts et al (2020) call for things like positionality statements and diverse individuals in the review process, their exclusion of the vast array of characteristics highlighted in Hommel’s review is not at all justified from a scientific standpoint (even though it is entirely justified from an activist standpoint of reparative justice). Given that a person’s positionality is some combination of the very long list of statuses, demographics, identities, beliefs, values, and experiences Hommel lists, indeed, it is the sum total of everything they are, identify with, have experienced, and have done and accomplished, it is hard to see how this will be implemented in any scientifically serious way (although it is quite easy to see how, restricting it to statuses relevant to progressive activist views of reparative justice and who is in protected v. unprotected categories, it could be implemented briefly). Adding “diverse individuals” in the review process makes a great deal of scientific sense if Hommel’s and the dictionary’s broad definition of diversity is used; and that includes (but is not restricted to) the far narrower types of diversity for which Roberts et al (2020) call.

Hommel’s second criticism, that racial identities may matter for some scientific questions but not others and that Roberts et al (2020) did little to demonstrate fundamental differences in the psychological processes based on race for scientific questions is also valid. Roberts et al (2020) failed to demonstrate or review evidence demonstrating widespread racial differences in any psychological phenomena or processes. Again, centering race without providing evidence that doing so makes much of a difference for many psychological phenomena is another tell that what is going on here is more activism than science. Do Black people simply not use the availability heuristic? Do Black people’s visual neurons respond differently to geometric shapes? These would be examples of fundamental psychological differences. It is surely true that, unless someone tests those possibilities we will never know, and doing so is just as surely worthwhile science. Scientifically, it would indeed be surprising if there were no differences at all in some of the psychological characteristics of Black and White people. Of course, scientifically, and consistent with Hommel’s critique, the same speculation about the potential existence of fundamental psychological differences applies to all the characteristics Hommel lists (such as sex/gender, culture, religion, SES, politics, intelligence, motivations, upbringing, experience, personality to name some, and there is probably an infinity of additional ones that he did not mention). The reasons to center race, ethnicity, or people of color are political/activist (reparative justice), not scientific, even though there are indeed good reasons to study people from every sort of background that exists (diversity in the first definitional sense, which does not reject but subsumes the second and certainly includes racial/ethnic identities).

Hommel’s final point, that agency (sometimes referred to as “self-selection”) may play some role in demographic distributional differences (for anything) is on solid scientific grounds, which should be obvious to anyone who has ever studied anything in psychology. He has not even argued that it does play a role, only that it might, and that this possibility isn’t considered in the Roberts et al (2020) paper at least with respect to editors, and with respect to their call for a variety of policies to eliminate what they believe are obstacles to psychologists of color. Anyone can see that Hommel’s criticism of this glaring omission is obviously true just by reading the Roberts et al (2020) paper.

Roberts et al (2020) do not refer to “self-selection” or “agency” explicitly anywhere in their paper. They nonetheless did present an example of agency in action. Their analysis of the relation between author race/ethnicity and the racial/ethnic makeup of the samples under study is clearly an example of an agency-based gap. The systemic racism hypothesis predicts biases favoring White people generally and, therefore, White participant samples. Therefore, when, developmental psychologists of color undersample White participants (Roberts et al [2020] reported this as 19%), presumably, they are choosing to do so. They are not being coerced into doing it by White supremacist individuals, policies or practices. If so, this is agency, and it obviously does explain part of the “gap” in racial sample composition across different race/ethnicity of author by field combinations.

As another example of how self-selection can at least partially explain some gaps that are routinely attributed to systemic biases, consider the gender gap in STEM. High achieving high school girls self-select into STEM fields less than do high achieving high school boys, at least in part, because high achieving girls tend to have more skills and therefore more options; having more options they are more likely to choose non-STEM options (Wang, Eccles & Kenny, 2013). High achieving boys, in contrast, are more likely to only be good at math and science and are more likely to pursue STEM fields because they have fewer other good options for professional careers (Wang et al., 2013). Evaluating the extent to which this explains gender gaps in STEM is beyond the scope of the present paper. It is sufficient to point out that the evidence that self-selection sometimes at least partially accounts for some gaps means that one cannot attribute gaps to bias unless one first rules out alternative explanations, such as self-selection. As Hommel argued, ignoring the possibility of self-selection (and other alternative explanations) should not be an option for scientific papers seeking to explain gaps.

The Epistemic Consequences of Politicizing Psychological Science

Just as manifestly obvious to anyone who has been paying attention, Hommel’s point about agency, however valid, is often on very dangerous political grounds, at least within academia. Even considering the possibility that underrepresentation in some desirable attribute stems from something about group differences (choices, culture, attitudes, skills etc.) rather than their victimhood constitutes grounds for social justice academics to denounce, mob, and ostracize (Honeycutt & Jussim, 2020; Stevens, Jussim & Honeycutt, 2020). If it is viewed as legitimate to only attribute gaps to discrimination, and, within academia, some sort of sacrilege to view them as resulting from other sources (except when those other sources are flattering to groups social justice academics deem worthy of favor), our “scientific” literature will be compromised to the point of uselessness.

Even when discrimination is the only source of some gap, we will never be able to know it with anything approximating scientific certainty, if researchers fear studying alternative explanations. Those alternatives can only be ruled out if they are studied; if many scientists fear to study them, they will not be studied or will be understudied. If they are not studied or are understudied, they cannot be ruled out. Similarly, even if alternatives to discrimination can be studied without fear of punishment, but only by researchers who either are members of the underrepresented group or have established reputations as fully committed to social justice as construed by activists, the risk of biased studies and unjustifiably canonized conclusions becomes high (Honeycutt & Jussim, 2020, in press). As such, the scientific benefits of diversity that come from clashing perspectives, dueling biases, and motivated skepticism will have been lost to psychological science. In such a situation, the extent to which the “scientific” literature reflects the underlying reality risks being severely compromised (Joshi, 2022).

These issues are all controversial. My view of the relative merits of the Roberts et al (2020) and Hommel articles may be a minority, at least in academia (although last I looked, truth is not determined by majority vote). Nonetheless, the best way to resolve controversies is to air them so people can see the evidence and arguments. Referring to the modern development within academia of denouncing claims that gaps and inequalities result from anything except oppression (and not referring to the Roberts et al, 2020 article per se, which did not denounce anyone), suppression is often something sought by political activists seeking power (Stevens et al, 2020); but it is terrible for science (Joshi, 2022; Krylov, 2021).

Diversity, Equity, and the Political Exclusion of the Vast Majority of Americans from Academia

I prefer a psychological scence that, when it promises a horse, delivers a horse. In this spirit, it is worth considering some data that can be used to compare academic claims about “diversity, equity, and inclusion” with an assessment of how diverse and how inclusive academia is on one of the dimensions highlighted by Hommel – politics. As we (Honeycutt & Jussim, in press) wrote: “Academia skews heavily left and the social sciences skew massively left (Langbert & Stevens, 2021). The skew is so extreme that, to those unfamiliar with the data, claims about the skew may sound like propaganda intended to delegitimize academia. In fact, some research has demonstrated that Americans–even those on the political right–underestimate just how massive the skew is (Marietta & Barker, 2019). But if extreme left skew constitutes justification for delegitimizing academia, then academia has delegitimized itself.” For example:

Langbert & Stevens’ (2021) study of party registration of over 12000 faculty found that the ratio of Democrats to Republicans in most elite social science departments ranged from a low of 3:1 in economics to a high of 42:1 in anthropology (in between was sociology, at 27:1).

Buss & von Hippel’s (2017) survey of over 300 social psychologists found that they voted for Obama over Romney by a ratio of 75:1.

Furthermore, many academics are not just on the left, they are on the extreme left. Honeycutt (2022) found that, in a survey of almost 4000 faculty from across the disciplines, 40% self-identified as radicals, activists, Marxists, or socialists (or some combination). In contrast, national surveys of Americans typically find that only 4-15% are on the far left (Hawkins, Yudkin, Juan-Torres, & Dixon, 2018; Pew Research Center, 2014).

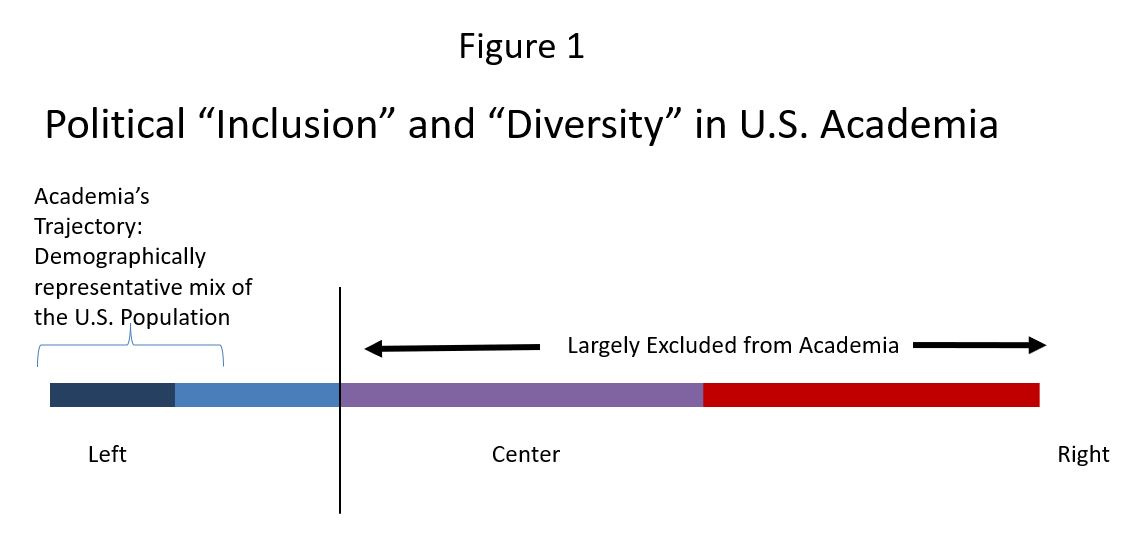

Figure 1 is a visualization that captures the state of “inclusion” and “diversity” in academia on the political dimension:

This then shows part of the mule that was delivered when the horse was sold. It seems unlikely to me that most Americans will view the academy as particularly inclusive if it functions, intentionally or not, to exclude the vast majority of Americans on political grounds. To be sure, self-selection/agency plays a role here, too, and perhaps the major role, but to the extent that the academy has created a hostile environment for those who dissent from far left politics, it bears more than a little responsibility for that self-selection (Honeycutt & Jussim, 2020). Furthermore, the historical facts are that it was not always this way (Duarte, Crawford, Haidt, Jussim & Tetlock, 2015), meaning that there is nothing inherent to academia that produces a massive skew of far left activists. Thus, the academy’s proclamations about inclusion, while the academy writ large functions to exclude most Americans, are likely to ring hollow and be viewed as the disingenuous propaganda of far left activists.

Science and Policy

Most Americans Reject Affirmative Action

Diversity in the narrow progressive sense advocated by Roberts et al (2020) and currently being implemented throughout academia is plausibly viewed as an extreme form of affirmative action. Pew has repeatedly found that large majorities of Americans of every racial/ethnic group they surveyed (including but not restricted to Black and Hispanic [the term they used] Americans) oppose use of race in college admissions and hiring (Graf, 2019; Horowitz, 2019). Similarly, California, a majority-minority state, and one of the most liberal, recently re-affirmed its ban on affirmative action ((Friedersdorf, 2020). From the purely scientifically valid “racial inclusion of participants is important for psychological science” standpoint that Roberts et al (2020) advocated, they should welcome such inclusive research (given how racially inclusive it was of participants); but from a political activist standpoint of advancing progressive values and academic DEI policies, such findings should be denigrated, dismissed, or ignored.

Build Effective Policies on Sound Science

None of this is to deny the ongoing presence of discrimination and other obstacles that uniquely affect members of some groups more than others. However, even Roberts et al (2020, p. 1306) declare that their “… work is not an indictment of psychological scientists…” Such problems are not likely to be solved, therefore, by targeting interventions at individual scientists. Inasmuch as recent research in both laboratory and real world contexts shows nonzero but very low levels of acts of discrimination in dyadic interactions (Campbell & Brauer, 2021; Nodtvelt, Sjastad, Skard & Thorbjornsen, 2021; Peyton & Huber, 2021), academia’s commitment to targeting individual behavior, such as requiring DEI statements for everything from job applications (Berkeley, 2022) to conference submissions (Society for Personality and Social Psychology, 2022) seems not merely misguided, but likely to do more harm than good. In the absence of evidence of high levels of individual acts of discrimination, such policies are not only a colossal waste of human time and effort but likely to accelerate the exclusionary functions highlighted here by dissuading individuals who refuse to profess allegiance to narrow progressive worldviews from entering academia (Thompson, 2019). If, however, professional organizations and institutions can identify ways in which their policies actively discriminate or create unfair obstacles that fall disproportionately on some groups, those organizations and institutions should identify and extirpate those policies.

In doing so, however, it will be important to keep in mind that the mere existence of policies in place when a gap has been identified does not constitute any evidence whatsoever that those policies discriminate or that removing or changing them is inherently beneficial. Consider traffic laws. Police can and have abused their power to issue more tickets to Black motorists (Pierson et al, 2020). The idea that this means we should abandon speed limits would be absurd. The dangers of eliminating speed limits are, perhaps, so obvious that my even mentioning it might seem like hyperbolic overreach. However, proposals far more extreme than eliminating speed limits have been taken quite seriously by progressive activists, including many in academia. The “defund the police” and related movements had enough credibility and success to be predictably followed by what has become known as “police retreat or pullback.” This was predictably followed by dramatic crime spikes, which themselves disproportionately victimized the very communities for whom such movements sought justice (Cassel, 2021; Reilly, Maranto & Wolf, 2022).

The implication for activist academics seeking to change the world should be clear: Tread lightly. Do not rush into implementing policies untested by rigorous research assessing effectiveness, costs, and unintended side effects. Do not rush into implementing even promising research-based policies without giving enough time for the findings to be vetted by skeptical scientists and policymakers (see, e.g., Sampson, Winship & Knight, 2013 for a detailed discussion of the complexities in doing so). As Fryar (2022) recently put it, “This is the key step that is missing in every DEI initiative I have seen in the past 25 years: a rigorous, data-driven assessment of root causes that drives the search for effective solutions. In other aspects of life, we would not fathom prescribing a treatment without knowing the underlying cause.”

Diversity (Broad Form) Can Improve Psychological Science

The cognitive arguments for diversity are often well-justified. Assuming a shared commitment to truth, evidence, and logically coherent interpretations of evidence, there are good reasons to believe that different experiences, values, and views can contribute to improving the quality of psychological science. This is likely a major reason why ethnically diverse teams have produced more influential papers (AlShebli, Rahwan & Roon, 2018) and politically diverse teams produce better Wikipedia articles, especially on political topics (Shi, Teplitskiy, Duede, & Evans (2019). Furthermore, different biases are necessary in order to maximize the skeptical vetting that is so crucial to the long-term scientific processes capable of producing valid conclusions (Merton, 1942/1973; Stanovich, 2021). The current political monoculture threatens the ability of psychology to produce valid conclusions on politicized topics (for reviews replete with concrete examples of the canonization of demonstrably false conclusions on politicized topics, see Crawford & Jussim, 2018; Honeycutt & Jussim, 2020, in press; Martin, 2015; Smith, 2014).

This then has the downstream consequence of undermining the credibility of psychology and other social sciences as the wider public begins to understand it. In a large national survey, for example, Marietta & Barker (2019) found that the greater the political skew that people believe characterizes academia, the less credibility is given to its scholarship.

It should therefore not be surprising that, as psychologists and other social scientists embrace and justify embedding full-throated political activism in their scholarship, academia will come to be justifiably viewed as an engine for progressive politics. This is already evoking exercises of political power by those who oppose progressive politics, exemplified by Florida’s Republican governor and legislature recently voting to undermine tenure protections in the Florida system (Tampa Bay Times, 2022). As ham-handed and harmful as this may be, it is a politically inevitable response to academia’s embrace of a progressive monoculture and political activism. Political battles will be fought using political tools, and not exclusively in the pages of peer reviewed journals or DEI committees. It would not be surprising to discover that cuts to government funding of social science are among the next targets in the sights of politicians who oppose the academic far left.

Conclusion: Free Inquiry is Crucial to Psychological Science and Maximally Inclusive of the Diverse forms of Diversity

Although individual scientists surely have their biases, as a field, maximizing the validity of psychological science can best be accomplished by free inquiry. Free inquiry in psychological science inherently involves embracing credible and rigorous voices, regardless of identity status or other group memberships or personal characteristics. Free inquiry includes the intense organized skepticism that Merton (1942/1973) argued was a critical norm of science; as such, it is some insurance that bad policies and bad conclusions will be identified. It is insurance against the epistemic follies identified by Joshi (2022) that can be produced by an academic culture of denunciation and suppression. As such, free inquiry by a diversity of voices in the first, broad definitional sense of diversity, unfettered by the demands and sanctions of those who would impose their subjective values on others, is maximally inclusive in the most meaningful sense.

The best of Roberts et al’s (2020) arguments constitute a call for including the excluded, at least if they are committed to the norms of science and to making coherent, evidence-based, logical arguments. I endorse these best arguments. In this spirit, I end this piece with quotes from scholars of color whose ideas and views relevant to issues in psychology closely related to those raised by Roberts et al (2020) and Hommel, and which I almost never see referenced or discussed in academic psychology literatures (especially ironic, since at least one, McWhorter, is a linguist and is highly influential on psychology-related topics [such as racism and intolerance] outside of academic psychology). None are psychologists, and I list their fields in a spirit of diversifying the field of ideas from which academic psychology draws. I note that this is not a sample of quotes representative of anything at all; it is a convenience sample of voices of people of color that have been largely excluded from scientific psychology.

Wilfred Reilly (2021, political science): “…people of color are successful in modern America to an almost surprising degree, which is rarely discussed—for different reasons—by either the “social-justice” left or the contemporary hard right. As of 2019, seven of the top 10 American ethnic groups in income terms—Indian, Taiwanese, Filipino, Indonesian, Persian, and Arab Lebanese Americans—were “people of color” as this term is generally conceptualized…”

Hrishikesh Joshi (philosophy, 2022): “…social pressure to avoid sharing evidence against a particular claim undermines the confidence we can place in that claim, because it makes more likely the possibility that the (first-order) evidence that does make its way to us is a lopsided subset of the total. This has the perhaps tragic implication that we can typically be less confident of morally and politically laden issues than we can about ‘dry’ subjects like chemistry or cell biology.’”

George Yancey (sociology, quoted in Kristof, 2016): ““Outside of academia I faced more problems as a black,” he told me [Kristof]. “But inside academia I face more problems as a Christian, and it is not even close.”

Luana Maroja (2022, biology): “Extreme emphasis on sexual harassment stifles productive scientific discourse between men and women.”

Musa al-Gharbi (2020, sociology): “Diversity is important. Diversity-related training is terrible.”

Marisol Quintanilla (2022, entomology): “It is very strange that the surveys assume that race is fixed when it is really a spectrum (for example I have Spanish, Chinese, North African, and Native American ancestries) and the same forms pretend that gender is on a spectrum (11 options in most Michigan State surveys) when it is clearly binary (mammals are sexually dimorphic).”

John McWhorter (2021, linguistics): “Woke racism: How a new religion betrayed Black America” (book title).

Roland Fryar (2022, economics): “More corporate leaders should be trying to solve diversity challenges in the same way they solve problems in every other aspect of their business: through intelligent use of data, rigorous hypothesis testing, and honest inference about what is working.”

Amna Khalid (2022, history): “Having grown up under a military dictatorship in Pakistan, I know well what happens when freedom of expression is threatened and people are bullied into silence. It pains me deeply to see this happening in my adopted country.”

Sarah Haider (2022, Founder, ex-Muslims of North America): “The activist game, to sum in one sentence, is about results… The thinker game is about truth… Years ago I was asked on a podcast whether it was possible to be effective and intellectually honest in the activist space. I said no.”

As psychology and academia embrace activism in the name of social justice, calls to include the previously excluded will likely accelerate. In that spirit, I look forward to responses by academics calling for DEI that celebrate the inclusion in this article, and therefore, in the psychology peer reviewed literature, of the heretofore excluded voices of people of color quoted above, and, more important, their substantive views. Doing so might help psychology to deliver that horse it sold.

References

al-Gharbi, M. (2020). Diversity is important. Diversity-related training is terrible. Retrieved on 9/2/22 from: https://musaalgharbi.com/2020/09/16/diversity-important-related-training-terrible/

AlShebli, B. K., Rahwan, T., & Woon, W. L. (2018). The preeminence of ethnic diversity in scientific collaboration. Nature Communications, 9(1), 1-10.

Berkeley, University of California (2022). Rubric for assessing candidate contributions to diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging. Retrieved on 9/5/22 from: https://ofew.berkeley.edu/recruitment/contributions-diversity/rubric-assessing-candidate-contributions-diversity-equity

Brothers, K. B., Bennett, R. L., & Cho, M. K. (2021). Taking an antiracist posture in scientific publications in human genetics and genomics. Genetics in Medicine, 23(6), 1004-1007.

Buss, D. M., & Von Hippel, W. (2018). Psychological barriers to evolutionary psychology: Ideological bias and coalitional adaptations. Archives of Scientific Psychology, 6(1), 148.

Campbell, M. R. & Brauer, M. (2021). Is discrimination widespread? Testing assumptions about bias on a university campus. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 150(4), 756–777. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000983

Cassell, P. G. (2020). Explaining the recent homicide spikes in US cities: The “Minneapolis Effect” and the decline in proactive policing. Federal Sentencing Reporter, 33(1-2), 83-127.

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Jones, M. R., & Porter, S. R. (2020). Race and economic opportunity in the United States: An intergenerational perspective. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2), 711-783.

Crawford, J. T., & Jussim, L. J. (Eds.). (2017). The politics of social psychology. Psychology Press.

Duarte, J. L., Crawford, J. T., Stern, C., Haidt, J., Jussim, L., & Tetlock, P. E. (2015). Political diversity will improve social psychological science. Behavioral and brain sciences, 38.

Friedersdorf, C. (2020). California rejected racial preferences, again. The Atlantic, November 20. Retrieved on 9/3/22 from: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/11/why-california-rejected-affirmative-action-again/617049/.

Gambrill, E., & Reiman, A. (2011). A propaganda index for reviewing problem framing in articles and manuscripts: An exploratory study. PLoS One, 6(5), e19516.

Graf, N. (2019, February 25). Most Americans say colleges should not consider race or ethnicity in admissions. Pew Research Center; Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/02/25/most-americans-say-colleges-should-not-consider-race-or-ethnicity-in-admissions/

Fryar, Jr., R. G. (2022). It’s time for data-first diversity, equity, and inclusion. Fortune (June 20). Retrieved on 9/5/22 from: https://fortune.com/2022/06/20/data-first-diversity-equity-inclusion-careers-black-workers-gender-race-bias-dei-roland-fryer/

Fryar Jr., R. G. (2011). Racial inequality in the 21st century: The declining significance of discrimination. In Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 4, pp. 855-971). Elsevier.

Haider, S. (2022). On effective activism and intellectual honesty. Hold that Thought. Retrieved on 9/2/22 from:

Hawkins, S., Yudkin, D., Juan-Torres, M., & Dixon, T. (2018). Hidden tribes: A study of America’s polarized landscape. Retrieved on 1/10/21 from: https://hiddentribes.us/media/qfpekz4g/hidden_tribes_report.pdf

Hommel, B. (in press). Dealing with diversity in psychology: Science or ideology? Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Honeycutt, N. (2022). Manifestations of political bias in the academy. Unpublished doctoral dissertation in progress.

Honeycutt, N. & Jussim, L. (in press). Political bias in the social sciences: A critical, theoretical, and empirical review. To appear in C.L. Frisby, R. E. Redding, W. T. O’Donohue & S. O. Lilienfeld (Eds.), Ideological and political bias in psychology: Nature, scope and solutions. New York: Springer.

Honeycutt, N., & Jussim, L. (2020). A model of political bias in social science research. Psychological Inquiry, 31(1), 73-85.

Horowitz, J. M. (2019). Americans see advantages and challenges in country’s growing racial and ethnic diversity. Pew Research Center. Retrieved on 3/13/22 from: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/05/08/americans-see-advantages-and-challenges-in-countrys-growing-racial-and-ethnic-diversity/

Index Mundi (2022). United Kingdom demographics profile. Retrieved on 9/3/22 from: https://www.indexmundi.com/united_kingdom/demographics_profile.html

Joshi. H. (2022). The epistemic significance of social pressure. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Khalid, A. (2022). Welcome to Banished! Banished. Retrieved on 9/2/22 from:

Kristof, N. (2016). A confession of liberal intolerance. New York Times, May 7). Retrieved on 9/2/22 from: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/08/opinion/sunday/a-confession-of-liberal-intolerance.html?_r=1

Krylov, A. I. (2021). The peril of politicizing science. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 12(22), 5371-5376.

Langbert, M., & Stevens, S. T. (2021) Partisan registration of faculty in flagship colleges, Studies in Higher Education, DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2021.1957815

Maroja, L. (2022). Extreme emphasis on sexual harassment stifles productive scientific discourse between men and women. Heterodox STEM, retrieved on 9/2/22 from:

Marietta, M., & Barker, D. C. (2019). One nation, two realities: Dueling facts in American democracy. Oxford University Press.

Martin, C. C. (2016). How ideology has hindered sociological insight. The American Sociologist, 47(1), 115-130.

McWhorter, J. (2022). Woke racism: How a new religion betrayed Black America. Penguin.

Merton, R.K. (1942/1973). “The Normative Structure of Science”, in: R.K. Merton, The Sociology of

Science: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations. The University of Chicago Press.

Nodtveldt, K. B., Sjastad, H., Skard, S. R., Thorbjornsen, H., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2021). Racial bias in the sharing economy and the role of trust and self-congruence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000355

Peyton, K. & Huber, G. A. (2021). Racial resentment, prejudice, and Discrimination. Journal of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1086/711558

Pew Research Center (2014). Political polarization in the American public. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/

Pierson, E., Simoiu, C., Overgoor, J. et al. A large-scale analysis of racial disparities in police stops across the United States. Nature: Human Behavior, 4, 736–745 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0858-1

Quintanilla, M. (2022). The new gender ideology is being used to coerce speech at universities. Heterodox STEM. Retrieved on 9/2/22 from:

Reilly, W. (2021). The good news they won’t tell you about race in America. Commentary, April), retrieved on 9/2/22 from: https://www.commentary.org/articles/wilfred-reilly/race-in-america-good-news/

Reilly, W., Maranto, R., Wolf, P. (2022). Did Black Lives Matter save Black lives? Commentary (September). Did Black Lives Matter save Black lives? Retrieved on 9/5/22 from: https://www.commentary.org/articles/wilfred-reilly/did-black-lives-matter-save-black-lives/

Roberts, S. O., Bareket-Shavit, C., Dollins, F. A., Goldie, P. D., & Mortenson, E. (2020). Racial inequality in psychological research: Trends of the past and recommendations for the future. Perspectives on psychological science, 15(6), 1295-1309.

Roberts, S. O., & Rizzo, M. T. (2021). The psychology of American racism. American Psychologist, 76(3), 475.

Sampson, R. J., Winship, C., & Knight, C. (2013). Translating causal claims: Principles and strategies for policy-relevant criminology. Criminology & Public. Policy, 12, 587.

Shi, F., Teplitskiy, M., Duede, E., & Evans, J. A. (2019). The wisdom of polarized crowds. Nature human behaviour, 3(4), 329-336.

Smith, C. (2014). The sacred project of American sociology. Oxford University Press.

Society for Personality and Social Psychology (2022). Demonstrating our commitment to anti-racism through programming and events. Retrieved on 9/5/22 from: https://spsp.org/events/demonstrating-our-commitment-anti-racism-through-programming-and-events#:~:text=As%20a%20society%2C%20SPSP%20values%20diversity%20and%20inclusiveness,SPSP%20standing%20committees%2C%20staff%2C%20MAL%E2%80%99s%2C%20and%20general%20members.

Stanovich, K. (2021). The social science monoculture doubles down. Quillette, August 30. Retrieved on 9/5/22 from https://quillette.com/2021/08/30/the-social-science-monoculture-doubles-down/

Statistics Canada (2019). Diversity of the Black population in Canada: An overview. Retrieved on 9/3/22 from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89-657-x/89-657-x2019002-eng.pdf?st=U_cmRKdw

Stevens, S. T., Jussim, L., & Honeycutt, N. (2020). Scholarship suppression: Theoretical perspectives and emerging trends. Societies, 10(4), 82.

Tampa Bay Times (April 19, 2022). DeSantis signs bill limiting tenure at Florida public universities. Retrieved on 9/2/22 from: https://www.tampabay.com/news/education/2022/04/19/desantis-signs-bill-limiting-tenure-at-florida-public-universities/

Thompson, A. (2019). The university’s new loyalty oath: Required ‘diversity and inclusion’ statements amount to a political litmus test for hiring. Wall Street Journal, December 19. Retrieved on 9/5/22 from: https://felleisen.org/matthias/Articles/loyalty.pdf

USAFacts (2022). Retrieved from on 9/2/22 from: Census data https://usafacts.org/data/topics/people-society/population-and-demographics/our-changing-population?endDate=2021-01-01&startDate=1972-01-01

United States Census Bureau (2022a). Explore Census data. Retrieved on 9/5/22 from: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?t=-01%20-%20All%20available%20basic%20races%20alone%3AIncome%20%28Households,%20Families,%20Individuals%29&tid=ACSSPP1Y2019.S0201

United States Census Bureau (2022b). Explore Census data. Retrieved on 9/5/22 from: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=Income%20%28Households,%20Families,%20Individuals%29&t=-A0%20-%20All%20available%20ancestries

Wang, M. T., Eccles, J. S., & Kenny, S. (2013). Not lack of ability but more choice: Individual and gender differences in choice of careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Psychological science, 24(5), 770-775.

Excellent paper. White and Black are nonsense categories anyway. Descendants of American slaves, Afro-Caribbeans and recent African immigrants are three very distinct groups. Euro-Americans are also highly diverse. Melanin content of skin is not a useful sorting category except for things such as vitamin D deficiency risks.

Great essay. Thank you... interestingly, I don't think the colloquial racial categories used by academics make much sense, anymore (if they ever did). I made this point in a recent post: "When ‘Black’ & ‘Hispanic’ Students Outscore ‘Asian’ & ‘White’ Students on the ACT, Nobody Notices."

https://everythingisbiology.substack.com/p/when-black-and-hispanic-students

I don't think anyone is really interested in diversity, anymore. It's about status...