Debunking the New "Glass Ceiling Index"

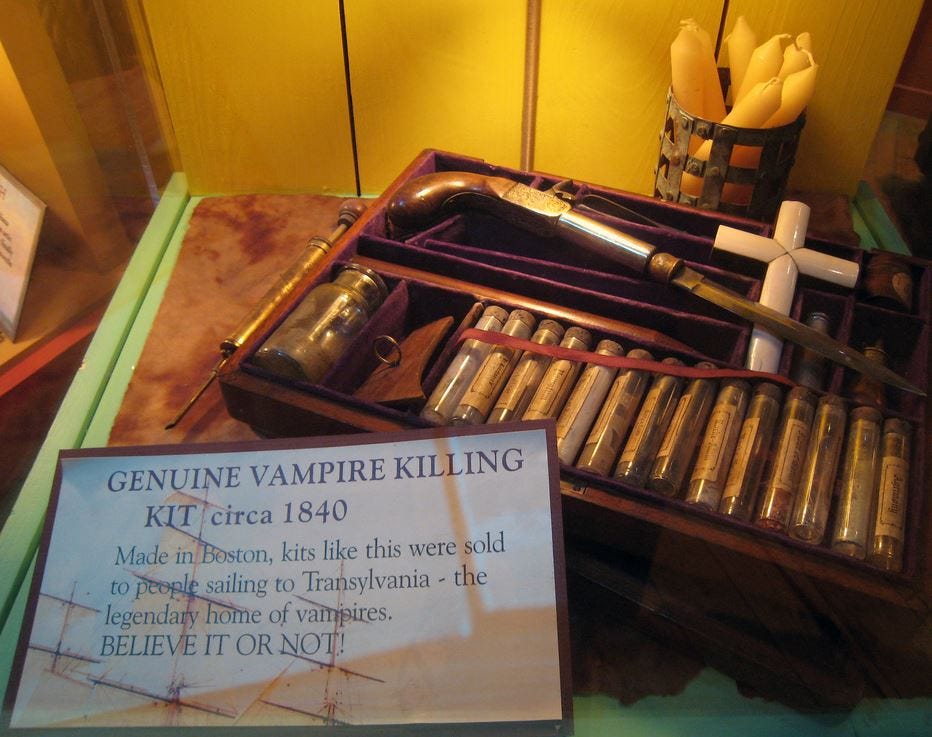

Initial, Experimental, "Wooden Stake Point"

Introducing Wooden Stake Points

For now, I am calling these “Silver Bullet Points.” Wooden Stake Points.1 Wooden Stakes kill vampires. And killing the academic claims and norms that suck the blood out of social science validity and credibility is exactly my goal here.

There is so much bad social science out there, it is impossible to debunk it all. But I am experimenting here with “flash” entries. These will be shorter essays that will focus on a single very bad aspect of some published scholarship. So a study might do 30 different things, but if I think one is very bad I am envisioning these sorts of entries as just debunking that one bad thing. Of course, the rest of the article may or may not be fine, though I will usually select something that I think is kinda central to the article’s point.

Each stake will target one vampire. This won’t end social science vampirism. But:

Maybe, others will join the fight. See this excellent entry by science reformer Stuart Ritchie, debunking a study purporting to show racism in dog-naming.

Even if lots of people join the fight, at best, the vampires will retreat, I doubt they will ever disappear completely. But this might, just might, in the long run, not anytime soon, upgrade the quality of the “peer reviewed social science.” Not likely, but maybe.

Even if the vampires don’t retreat at all, at least you will witness some of the ways to fend them off, and this might, just might, offer you some vampire protection against credulously believing sophisticated-sounding peer reviewed nonsense.

PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE reply and let me know if you think reading this was worthwhile. As a natural dissident and contrarian, and advocate for intellectual diversity, this includes those of you who did not like this! Either way, I’d like to hear from you.

Delusions of Glass Ceilings

In a recent article titled Equal Representation Does Not Mean Equal Opportunity: Women Academics Perceive a Thicker Glass Ceiling in Social and Behavioral Fields Than in the Natural Sciences and Economics, the authors created what they called a “Glass Ceiling Index.” "Glass ceiling” refers to a barrier to women’s achievement or advancement.

This is how they described their Glass Ceiling Index:

“…we introduce a novel, more indirect operationalization, namely, a perceived Glass Ceiling Index (GCI). We asked two separate questions: First academics were asked to think about the people in their direct working environment, and to estimate the ratio of women to men among their direct colleagues. Subsequently, academics were asked to estimate the gender ratio for at the full professor level in their department. We subtracted the perceived gender ratio at the colleague level from the perceived gender ratio at the top level (i.e., full professor level). This creates a GCI index where a score of 0 indicates similar gender representation at both levels, and a score GCI > 0 indicates a perceived glass ceiling (i.e., the proportion of women is lower in academic leadership relative to ranks below).”

First a red flag. I found only their characterization of the GCI questions, but I could find nothing in the report presenting the exact wording of the questions.

What are “people in your direct working environment”? All the faculty in your department? The faculty next door? The faculty you happen to run into most of the time at work? The people you mostly collaborate with? Who knows?

Let’s put that aside for now.

GCI= estimated (F:M in “direct working environment”) - estimated (F:M among full professors).

They say: “a score GCI > 0 indicates a perceived glass ceiling.” The idea, apparently, is that if someone perceives a lower ratio of women among full professors than among professors in their “direct working environment” then they perceive barriers to women.

But is that what GCI>0 means?

Let’s consider a situation in which there is no barrier to women’s promotion to full professor. Could you still get GCI>0? Of course you could. Here are two ways, though I suspect there are many more:

Cohort effects. In most fields, men were vastly more likely to become professors from the beginning of the existence of colleges and universities. This is undoubtedly a discrimination effect. Back then. It usually takes 10-20 years to become a full professor. So if 90% of faculty were men in that department circa 1990, and most of them eventually became full professors, and the gender balance slowly became more equal or even flipped (with more women than men being hired, say, in the last 10 years), most of the full professors will be men. If faculty have any tendency to hang around with other faculty near their own age or level of seniority (e.g., untenured faculty with other untenured faculty), and there are more women among less senior faculty, bingo, GCI>0. No glass ceiling needed.

Gender sorting of “direct environments.” Let’s say that women tend to work more closely with women than with men. All this needs to be is a modest tendency; obviously there are lots of collaborations among women and men. But if there is even a modest such tendency, there could well be more women in women’s “direct working environments” than among professors in general (including but not restricted to full professors). GCI>0 without a glass ceiling. Again.

It then goes downhill from there. Perceiving a demographic difference is not equivalent to perceiving an unfair obstacle. One can perceive that professional athletes are almost all young adults and yet perceive no “age floor” preventing the entry of the elderly into professional baseball, basketball, tennis, etc. One can perceive that HR is run by mostly women without perceiving anti-male biases in HR. Of course, it is possible that one does see these differences as obstacles too. But that is the point — the GCI does literally nothing to indicate when people do versus do not perceive obstacles.

Labeling Bias: How to Reach a Dramatic Conclusion on the Cheap

The GCI is a classic example of “labeling bias.” Labeling bias involves giving measures or some result a name that implicitly imports a conclusion without actually empirically demonstrating that the conclusion is true. “Implicit bias,” “symbolic racism,” “denial of environmental realities” and “microaggressions” are all examples of the sort of thing whereby the main conclusion is reached by giving a snappy label rather than providing evidence that the conclusion is actually true.

To be sure, glass ceilings were once very powerful, and we are still living with the longterm damage that they have done. Furthermore, glass ceilings still do exist, and are worthy of both scholarly study and activist efforts to destroy. No one should be held back from advancement for any reason other than lack of merit, certainly not because they belong to a particular demographic group.

Activism, Scholarship, Poop

But the issue here is not “are glass ceilings bad” (yes they are). The issue here is “given that the GCI was interpreted as a clean measure of perceived barriers to women, and it isn’t, what is going on?”

We could view the paper through a lens of “activism masquerading as scholarship.” Politics is all about winning, about getting what you want. An article that can be used as rhetoric condemning the modern persistence of glass ceilings in the academy is incredibly useful for activists. Hey, its peer reviewed science!

Nonetheless, this sort of work trivializes and distracts from the actual understanding of actual glass ceilings. The “GCI” is bullshit (in the academic sense of “impressive-sounding claims without a direct concern for truth”). When such work is revealed as bullshit, it risks undermining support for justified policies designed to break actual glass ceilings.

Maybe they did have a “concern” for truth, but just went awry looking for it. No one’s perfect. However, (typically) at least two peer reviewers and the editor thought this was great stuff to publish. Epic system fail.

I will leave you with this wonderful quote from science reformer and statistician Andrew Gelman:

Comments welcome and invited. Was this worth reading? Should I do more of these Wooden Stake Points? Or should I bag this line of writing? Thanks in advance.

Mitch Brown correctly pointed out that silver bullets kill werewolves, not vampires. Its too bad, because silver bullet sounds so cool. But truth is truth, even when dealing with Supernatural Forces.

I thought this was a worthwhile essay. Thanks for writing it.

Thanks to those of you who have replied. I also received some positive comments via email, and on Twitter. I suppose people might be reluctant to express negative ones, even though I did my best to be as inviting as possible. I do not want to clutter anyone's inbox with stuff most don't value.

As this Sub is new, I plan to continue experimenting. The core will be longform essays, like the first on academic radicalization and the second on microaggression research. There will be more Wooden Stakes down the road, and maybe at least 1-2 other shortform essay types, at least at first.