In this post, I summarize the findings from one of the studies reported in the paper shown below, and which is more or less in press.1

My prior post presented an overview of the working theory, which is that social media use lends itself to botification: a process by which people’s social media interactions, and, we argue, their underlying psychology while using social media, become more bot-like (bots are programs designed to simulate real people online, often to promote simplistic narratives, propaganda and to sew discord). We proposed that botification represents a cognitive state in which individuals rely heavily on mental shortcuts and heuristic-driven behaviors, mirroring the reactive and automated processes of a computer program or algorithmic bots. This includes sometimes enthusiastically or even gleefully promoting the erosion of trust in civic and democratic practices and institutions.

Key Findings

People who support democracy in general often do not support it in specific instances.

Social media use correlated with lower support for democracy in specific instances.

Here is the model and link to the prior post, which has lots of narrative details about the model:

The Botification of Some Americans' Minds

In this post, I summarize the working theory for one of our papers, which is more or less in press. Followup posts will present the results from two empirical studies of botification.

What is Civic Disalignment?

We used the term, “civic disalignment,” to refer to disconnects between individuals’ professed civic ideals and their endorsement of real-world anti-civic behaviors. While individuals may say they endorse democratic principles when presented as abstractions (e.g., free speech, majority rule, etc.), many endorse anti-democratic actions when confronted with concrete situations (such as extremist speech or overturning an election won by an extremist). In the 1950s, vast majorities of respondents in two surveys claimed to endorse democracy, even though majorities or large minorities also endorsed very anti-democratic actions — censorship of controversial speakers and overturning elections if the “wrong” type of person won (Prothro & Grigg, 1960).

For example, Prothro & Grigg (1960) found that over 90% of their samples agreed with these general principles:

However, this overwhelming consensus of support for democratic principles broke down when people were asked to consider specific instantiations of these principles:

Almost everyone agreed that every citizen should have an equal chance to influence govt policy, but more than half also agreed that only the informed and taxpayers should be allowed to vote. Almost all agreed that public officials should be chosen by majority vote, unless the winner was a communist; then, more than half said that the commie who won should be barred from office. Almost all agreed that the minority should be free to criticize the majority, but over a third would prohibit an anti-religious speech and over half would prohibit a communist speech.

This disconnect between professed support for democratic principles and willingness to chuck those principles down the garbage if applied to the “wrong” person is civic disalignment.

Virtual Civic Disalignment

Virtual civic disalignment refers to the role social media can play in catalyzing these sorts of disconnects between professed commitments to democracy in the abstract and willingness to support anti-democratic actions in the real world. Social media is justifiably not known for its ponderous content about abstract issues such as democracy; as such, we expected it to be largely unrelated to endorsement of democratic principles such as majority rule, minority rights, and rule of law.

Instead, social media is often a forum for simplistic and emotionally-charged content, often about recent concrete real world events. Abstract commitments to due process are easily forgotten in the heat of a social media mob denouncing someone for some supposedly horrendous moral transgression that has probably only been reported simplistically and incompletely. Abstract commitments to majority rule can easily be abandoned if the winner of a particular election is seen as evil incarnate. Abstract commitments to minority rights can easily be abandoned if that minority is deemed sufficiently dangerous or extreme. Thus, the virtual civic disalignment hypothesis is that those who spend more time on social media are also more likely to endorse anti-democratic actions in concrete instances in the real world.

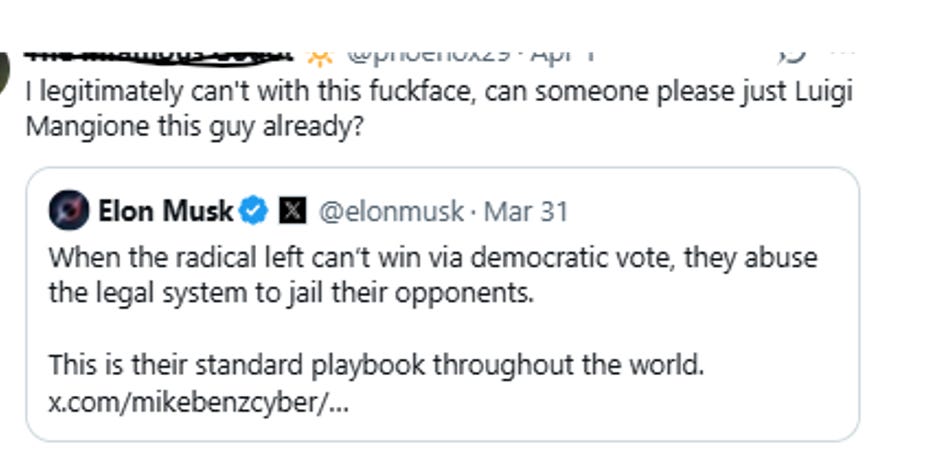

These points are illustrated anecdotally by the dynamics on display in tweets shown below. The person posting is retweeting an evidence-free propaganda post by Elon Musk seeking to demonize and delegitimize what he calls “the radical left.” However, Musk’s tweet is plausibly interpretable as referring to Democrats because actual radical leftists (e.g., communists, revolutionaries, etc.) do not win many elections in the U.S. and the tweet declares that when they lose (implying there are times they win) they abuse the legal system – potentially legitimizing a harsh and possibly illegitimate or illegal response. Such speech may be bad, but promotion of strong criticisms of one’s political opponents, including propaganda some might consider toxic, is legally protected speech in the U.S. (and for good reason – when governments get into the business of censorship, this “cure” is almost always worse than the disease).

Luigi Mangione is the person arrested for the murder of United Health Care CEO, Brian Thompson. Thus, calling to “Luigi Mangione” someone is a thinly-veiled call for murder, in this case, political murder. Regardless of how one views Musk’s tweet, the substance of the comment by the person who retweeted Musk is even worse than Musk’s tweet. The tweeter may well believe this is defending American democracy from “fascism,” but, if so, it is being done by glorifying political violence, which is a key feature of fascist and other authoritarian movements. We argue that this is how social media can encourage civic disalignment – endorsement of anti-democratic principles in the name of advancing democracy.

Study One: Botification And Civic Disalignment

We proposed that the process of botification and virtual civic disalignment are connected and mutually reinforcing. Although Study One2 was not designed to test causal hypotheses, its purpose was to explore whether such relationships exist, leaving causal questions for subsequent research. Accordingly, Study One tested the following hypotheses:

Social media use has little or no relation to general support for democratic principles in the abstract.

The civic disalignment hypothesis: Support for democracy in the abstract will have little or no relationship to endorsement of concrete democratic behaviors.

The botification hypothesis: Social media use predicts more endorsement of specific undemocratic behaviors.

The virtual civic disalignment hypothesis: This relation will hold even among those expressing higher levels of general support for democracy.

Sample

We surveyed 1,906 U.S. respondents, including a core sample of 1,500 participants stratified to match U.S. Census benchmarks for age, gender, and race. We also intentionally oversampled around 400 Gen Z and Millennial respondents because younger users are more likely to use social media.

Measures

The survey assessed support for abstract principles of democracy, and also their support for specific anti-democratic actions. We also assessed general sentiment toward democracy in the U.S. All measures were coded so that, for data analysis, a higher score indicated higher support for democracy. An online supplement presents the measures in detail.

General democratic sentiment. Three questions assessed participants’ general sentiment about American democracy (i.e., U.S. democracy has a bright future, U.S. democracy is currently working, democracy is the best form of government; see Supplement; Figures S1, S2, and S3). These were summed to create a general sentiment toward democracy scale.

Support for fundamental principles of democracy. Fundamental principles include things like majority rule, minority rights, and the rule of law. Therefore, questions assessed participants’ support for two fundamental democratic principles in the abstract taken directly from Prothro and Grigg’s (1960) classic study: elected officials should be chosen by majority vote, and the minority has the right to criticize majority decisions.

Endorsement of (anti)democratic behaviors. Next, we assessed participants’ willingness to endorse specific actions that challenge democratic principles (majority rule, free speech, rule of law). Participants evaluated politically and morally charged concrete situations in which those very same democratic principles were in play. Two questions assessed support for protestors preventing controversial speech (one involving opposition to gender affirming care; one involving support for late term abortions). Two questions assessed support for overturning elections won by extremists (one referring to a White supremacist, the other to a Communist); these were summed. Two questions assessed support for banning extremists from voting (one Nazi, one Communist); these were summed. Two other questions assessed banning people from voting for other reasons (uninformed, not taxpayers). All questions were scored such that higher scores reflected the more democratic response (e.g., not overturning an election, not banning extremists from voting, etc.).

Authoritarianism. To assess ideological rigidity and authoritarian tendencies, participants completed both the Short Right-Wing Authoritarianism Scale (Zakrisson, 2005; α = .76) and a brief Left-Wing Authoritarianism scale, LWAI-13 (Costello & Patrick, 2022; α = .83).

Social media use (SMU). We also collected self-reports of time spent on social media.

Results

Table 1 presents correlations among all variables. I realize that the font there is small, bordering on unreadable, but I could not get Substack to make it larger. So you can also find this table here.

The first hypothesis was that social media use (SMU) would have little or no relation to general support for democracy. Although the correlations of SMU with the three principles (majority vote, minority rights, equality before the law) were not large (rs = -.05, -.05, -.11), they were consistently negative, meaning higher SMU was associated with less support for abstract principles of democracy. Two of the correlations were trivial by our standards. Determining whether these results meaningfully disconfirmed our first hypothesis or are mere “crud” (as Meehl, 1990, would have described it) will have to be left for future research.

Our second set of analyses tested the civic disalignment hypothesis: Support for democracy in the abstract would have little or no relation to endorsement of concrete democratic behaviors. This was consistently confirmed. The 15 correlations between support for the three abstract democratic principles and the five concrete democratic behaviors were all quite low ranging from r=0 to a high of r=.09. As Prothro & Grigg (1960) found over 60 years ago, there is little connection between people’s professed endorsement of democratic principles and their application of those principles when they matter the most (e.g., when someone they find repulsive wins an office by majority vote).

Our third set of analyses tested the botification hypothesis: whether SMU predicts endorsement of specific undemocratic behaviors. Four of the six correlations of SMU with endorsement of undemocratic behaviors were above our “small” threshold (-.11< r < -.24) and reached the p<.001 level of statistical significance (see Table 1). All were negative, indicating that, as SMU went up, endorsement of the democratic option went down. The other two correlations with SMU (overturn election, only taxpayers allowed to vote) were also negative but trivial. When summed to create an overall index of support for anti-democratic behaviors, the correlation of SMU use was -.20 (p<.001) indicating that higher SMU was associated with lower support for democratic behaviors (greater willingness to violate basic principles of democracy).

It is also noteworthy, though not specifically predicted, that SMU was positively associated with left-wing authoritarianism (r=.32, p<.001). Although understanding why people high in LWA seem particularly attracted to SMU (or why SMU induces higher levels of LWA) is beyond the scope of the present research, understanding the nature of this relationship is an important direction for future research.

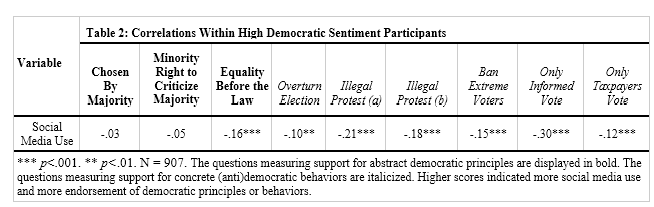

Last, we tested the virtual civic disalignment hypothesis, which predicted that even among people expressing strong support for democracy, SMU would correlate with endorsement of specific anti-democratic behaviors. This analysis focused only on participants scoring above the median on the democratic sentiment scale. Even within this seemingly high-democracy sentiment subgroup, SMU negatively correlated with each measure of support for democratic behaviors (see Table 2), and with the composite of the six endorsement of democratic practices items, r = -.25, p < .001. Even among those who otherwise express strong democratic values, higher SMU still predicted reduced support for democratic behaviors, supporting the virtual civic disalignment hypothesis.

The Key Limitation

Because the study is nonexperimental, the causal direction of these correlations cannot be determined. Perhaps social media attracts particularly undemocratic people. Perhaps social media erodes democratic norms and values. Perhaps both. Furthermore, there are likely alternative explanations for the negative relationship between social media use and endorsement of undemocratic actions. There are other limitations too, but I am trying to keep this post from going full academic egghead.

Bottom Lines

Civic disalignment has been around for a looong time. Probably predates Prothro & Grigg, and may go back to the founding of the U.S. Applying principles in a principled rather than partisan manner is pretty difficult. The Founders warned of the dangers of “faction” for just this (among other) reason(s). And lord knows we are up to our ears in “faction” now, though this has ebbed and flowed through all of American history (I’d have to track down the source, but I am pretty sure Washington once quipped something like, “If the Democrat-Republicans ran a piece of furniture for Congress, most of them would vote for it” — I will add a note here crediting you and revising this not-really-quote if any of you commenting can find the original quote).

Social media use appears to be contributing to civic disalignment either by causing botification or simply by attracting beehives of people already prone to civic disalignment, or both.

Social media has fundamentally altered the landscape of human interaction, shaping how individuals perceive themselves, engage with others, and participate in civic life. As a modern analog to the printing press, social media facilitates the rapid dissemination of ideas, emotions, and cultural narratives, offering unprecedented opportunities for connection and influence. However, the printing press was also deeply disruptive to European society, in part by making it far easier to communicate criticisms of existing institutions (Luther’s 95 Theses comes to mind) and was followed by 200 years of religious wars).

Despite the massive disruptions it facilitated, the printing press ultimately proved to be a gigantic boon to humanity because it made mass dissemination of knowledge and ideas possible for the first time in history. One can only hope that social media will ultimately provide a similar boon, preferably without a modern parallel to the 200 years of religious wars that followed the invention of the printing press.

References

Costello, T. H., & Patrick, C. J. (2023). Development and initial validation of two brief measures of left-wing authoritarianism: A machine learning approach. Journal of Personality Assessment, 105(2), 187-202.

Meehl, P. E. (1990). Appraising and amending theories: The strategy of Lakatosian defense and two principles that warrant it. Psychological inquiry, 1(2), 108-141.

Prothro, J. W., & Grigg, C. M. (1960). Fundamental principles of democracy: Bases of agreement and disagreement. The Journal of Politics, 22(2), 276-294.

Zakrisson, I. (2005). Construction of a short version of the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(5), 863-872.

Commenting

Before commenting, please review my commenting guidelines. They will prevent your comments from being deleted. Here are the core ideas:

Don’t attack or insult the author or other commenters.

Stay relevant to the post.

Keep it short.

Do not dominate a comment thread.

Do not mindread, its a loser’s game.

Don’t tell me how to run Unsafe Science or what to post. (Guest essays are welcome and inquiries about doing one should be submitted by email).

Footnotes

“More or less in press”? Joe Forgas has been running small, thematic social psychology conferences since the 1990s. The format is this: 1. Draft a paper; 2. Present the work as a talk at his conference; 3. Revise based on the other presentations and comments from a reviewer or two who reads the paper. Every conference so far has produced a published edited book of these chapters. This essay is based on one of two studies I will presenting at his conference in July, 2025. Forgas has our draft. So it is “more or less in press” though it will surely be revised before it actually gets published.

Study One. This implies that it is not the only study. It isn’t. There’s another. It will constitute the next post at Unsafe Science (unless something different that I MUST GET TO RIGHT AWAY pops up — then it will come after that).

"Support for fundamental principles of democracy. Fundamental principles include things like majority rule, minority rights, and the rule of law."

Here's the problem: They don't. Democracy is majority rule, and that's all democracy is. You don't find hypocrisy in someone who supports majority rule and then wants to 86 a minority; to the contrary, that's almost an extra-democratic belief!

Are there hypocrites in the world? Certainly. But in a world where it's said that peanut butter and jelly sandwiches are "racist", a lot of the "hypocrisy" is just two people defining terms differently.

It’s almost as though the post WWII governments decided to keep bogeyman targets as foil. Example: Romney was mocked by the establishment for calling Russia a geopolitical threat during the debate with Obama. Then the establishment’s 2007 Russian collusion case with Bob Dole was so unnoticed that they recycled it for Trump. They keep trying to make someone/something worse than [insert current agenda] to make current agenda look like the cure. “By any means necessary” is their force multiplier to incite violence. They know fully well that socially detached people will carry out these attacks. They’ve even allowed them to band and act together (BLM/Antifa).