Some Sex Differences are More Problematic than Others

April Bleske-Rechek and Michael Bernstein

April and Michael have become regular recent contributors to Unsafe Science, and I invite you to check out their prior contributions, which are definitely among my favorite guest posts, and which you can find here, here, and here. As most of you know, I ran afoul of an academic mob for calling bullshit on the narrow-minded, highly politicized progressive form of “diversity” as implemented throughout academia (or, more exactly, for calling “they promised a horse but delivered a mule”). It is amusing to note that the U.S. Supreme Court just banned most of what passes for diversity among that crowd. I mention this only because the research April and Michael report here elucidates a piece of the psychology underlying that mulishly dogmatic, narrow-minded form of diversity, at least with respect to sex.

Without any further ado…

By April Bleske-Rechek and Michael Bernstein

Rarely a day goes by that we don’t happen upon a new article, op-ed, or report bemoaning the continued underrepresentation of women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) jobs and upper-level corporate positions.

In fact, although female representation in STEM occupations has doubled since 1980 (see Figure 1 left panel below), and women’s representation in high status jobs has increased as well, massive efforts to ameliorate sex disparities in occupational representation continue.

Figure 1: Percent of Women and Men in STEM and HEAL (Health, Education, Administration, and Literacy) Occupations, 1980 and 2019. (Adapted from Figure 11-1, in Reeves, 2022, Of Boys and Men)

Or, more precisely, massive efforts to ameliorate some sex disparities continue. As Richard Reeves explained in his latest book, Of Boys and Men, the lack of gender parity in STEM continues to cause handwringing, while men’s under-representation in HEAL (Health, Education, Administration, and Literacy) occupations has substantially worsened since 1980 (Figure 1 right panel) yet continues to receive very little attention. Indeed, Katharina Block and her colleagues have shown that people are more supportive of social action to boost women’s representation in male-dominated jobs than they are of social action to boost men’s representation in female-dominated jobs.

We were intrigued by those data, particularly given what is so well known about sex differences in occupational interests (as well as values, personality traits, and cognitive strengths) and the relevance of those attributes for understanding both sexes’ occupational choices (for excellent reviews, see here or here). So, we designed two studies to further investigate people’s reactions to existing sex disparities in job representation.

STUDY 1

In our first study, we asked over 800 college students from a public university in the U.S. to read true statistics (taken from the U.S. Department of Labor) about one lower-paying and one higher-paying job in which either men or women are over-represented.

Participants were randomly assigned to read about either two male-dominated or two female-dominated jobs. As shown in the table below, there were two potential jobs of each type. Participants were asked their opinions about the jobs (see Figure 2).

Table 1: Job Sets for Study 1.

We also asked participants to rate how much of the gender gap (None of it to All of it) they thought was due to each of five factors:

Socialization/gender roles

Sexism/discrimination

Innate differences between the sexes in physical abilities

Innate differences between the sexes in mental abilities

Innate differences between the sexes in what they like to do

What did we find? Similar to what Block and colleagues found before, our participants judged male-dominated jobs as more problematic than female-dominated jobs. Three things are notable about these data, however: (1) the pattern is particularly pronounced for the women in our sample; (2) the pattern is particularly pronounced for higher-paying jobs; and (3) we observed this pattern despite each pair of male- and female-dominated jobs being described as of equal salary.

Figure 3: Agreement that the Gender Gap is “Problematic.”

You might think the pattern is due to people perceiving the male-dominated jobs as higher in status. But our participants’ status ratings did not fit well with that explanation. As shown in Figure 4, within each salary level, participants gave similar ratings to male-dominated and female-dominated jobs.

Figure 4: Agreement that the Job is High in Status

Instead, participants’ perceptions of the causes of the disparity were tied to their thoughts on how problematic the disparity is. The more participants perceived the gender disparities in job representation as due to sexism/discrimination (be they lower or higher paying jobs, or male or female-dominated jobs), the more problematic they perceived them to be (all rs ≥ .31).

And, as shown in the figure below, women more than men perceived gender disparities as due to sexism/discrimination – and that gap is larger for the male-dominated jobs of $50K or more.

Figure 5: Ratings of How Much of the Gender Gap is Due to Sexism/Discrimination.

STUDY 2

We refined our measures and conducted a follow-up study, this time with 612 U.S. MTurk workers. As in the first study, we provided true job statistics. Participants were randomly assigned to two male-dominated or two female-dominated jobs.

Table 2: Job Sets for Study 2

We found a very similar pattern to that documented in the first study. Specifically, participants of both sexes – but especially women - rated male-dominated jobs of $50,000 or more in pay as more problematic than female-dominated jobs at any level.

Figure 6: Ratings of How Problematic the Gender Gap Is.

To expand upon Study 1, we also asked them if affirmative action programs should be implemented to address the gender gap. Participants supported affirmative action more for male-versus female-dominated jobs. Women supported affirmative action more than men did.

Figure 7: Ratings of Whether Affirmative Action Programs Should be Implemented.

As in our first study, the pattern of reactions was not clearly explained by perceptions of job status. With the exception of chemistry professors being rated by both sexes as higher in status than social work professors, participants reacted quite similarly to male- versus female-dominated jobs of identical pay.

Figure 8: Ratings of Job Status.

There also was no clear link between individuals’ ratings of the status of a male-dominated job and how problematic they perceived that gender gap to be. In the $50K condition, men who perceived the female-dominated job (event planner) as higher in status also viewed the gender gap as less problematic; in the $110K condition, women who perceived the female-dominated job (pediatric physician) as higher in status also viewed the gender gap as less problematic.

Maybe women perceive male-dominated jobs as particularly problematic because they themselves wanted those jobs? But no, the women in our sample didn’t personally want the male-dominated jobs more than men did, nor did the women want male-dominated jobs more than they wanted female-dominated jobs.

Figure 9: Men’s and Women’s Ratings of How Much They, Personally, Would Like to be Employed in the Job.

In Study 2, when we asked participants to explain each gender gap, we presented six factors (in random order) to sum to 100%:

socialization/gender role expectations for men and women

sexism/discrimination against (the overrepresented sex)

sexism/discrimination against (the underrepresented sex)

innate differences between the sexes in physical abilities

innate differences between the sexes in mental abilities

innate differences between the sexes in what they like to do

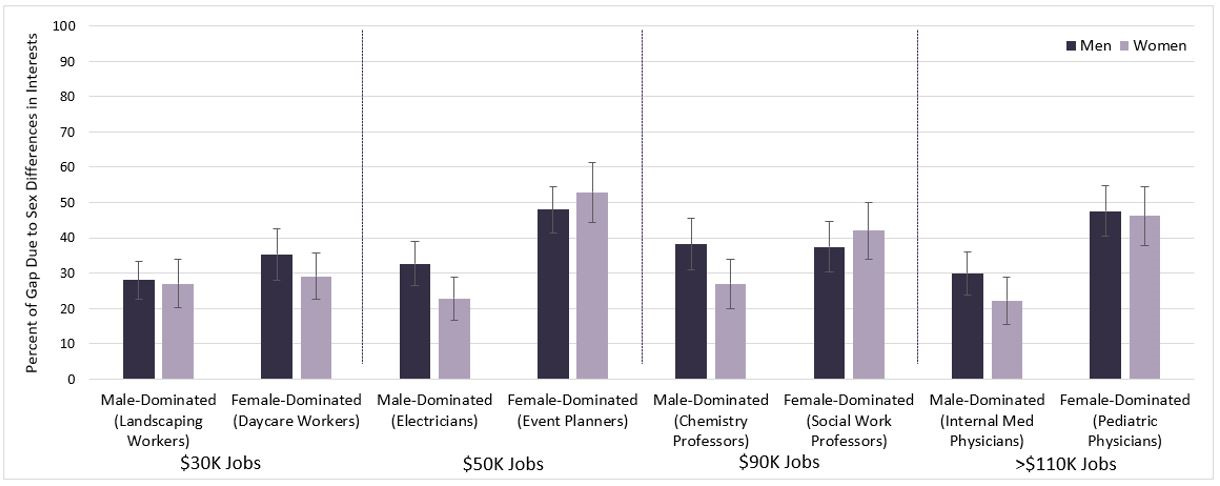

The notable differences played out in participants’ allotments to sexism/discrimination (against the underrepresented sex) and innate differences between the sexes in what they like to do (interests). The figures below can be summarized as follows: For medium to very high paying jobs in which men are over-represented, both sexes – but especially women – viewed sexism/discrimination as a contributor to the gap. For jobs in which women are over-represented, sexism/discrimination was largely irrelevant, and sex differences in interests picked up the slack. Unsurprisingly, correlational analyses also showed that the more participants attributed a gap to sexism/discrimination, the more problematic they perceived it to be, and the more they attributed a gap to sex differences in interests, the less problematic they perceived it to be.

Figure 10: Ratings of the Portion of the Gap Due to Sexism/Discrimination.

Figure 11: Ratings of the Portion of the Gap Due to Innate Differences Between the Sexes in What They Like to Do.

In sum, we can offer four observations from these two studies:

1. Both men and women, but especially women, perceive male-dominated jobs as more problematic and worthy of governmental intervention to promote equity than female-dominated jobs of identical pay;

2. This differential reaction to male-dominated versus female-dominated jobs is not explained by differential perceptions of how high status those jobs are or how much people say they want those jobs;

3. Instead, both men and women, but especially women, attribute male-dominated jobs more than female-dominated jobs to sexism/discrimination; and

4. The degree to which people attribute gender gaps to sexism, the more problematic they perceive the gaps to be.

Our findings are striking because sex disparities in these jobs make complete sense given what we know about differences between males and females in interests, temperament, and cognitive ability profiles! These differences between males and females (1) are robust;1, 2, 3, (2) are often even more pronounced in countries that are more gender egalitarian;4, 5, 6 (3) manifest early in life7, 8 and in our non-human primate cousins;, 9, 10 and (4) are tied to sex-differentiated biological factors such as androgen exposure.11,12,13,14

To be sure, by acknowledging that sex differences have biological underpinnings, we are not suggesting that biology is destiny; our dispositions operate within the context of our environments. Regardless, whatever their causes, aggregate differences between the sexes in psychological attributes have consequences, including for occupational choice.

We question the presumption that sexism/discrimination is an explanation for women’s lower representation in some jobs. Although sexism and discrimination undoubtedly still play some non-zero role in understanding women’s differential representation in certain jobs, there is reason to think that role is minor. For one, women are more likely to be qualified for a variety of jobs, given they now earn 140 baccalaureate and post-baccalaureate degrees for every 100 earned by men. Moreover, international field experiments of common jobs show no evidence of hiring discrimination against women; and in academic science in the U.S., women are favored.

The heart of the issue may be that – at least in the West - we value women’s survival and well-being more than we value men’s, and thus attend more to any possibility of their mistreatment. For example, scientists cite studies that portray bias against women at a much higher rate than they cite studies that portray bias against men. And, as explained by Clark and Winegard, people react more negatively to research that makes women look bad than to research that makes men look bad. With such concern for females, then, perhaps we should not be surprised that the majority of today’s high school students think women are discriminated against in the professions and getting a college education -- despite women’s representation among college graduates and in leadership positions being higher than ever.

We close, then, with the following questions: What level of female representation would people need to see in (currently) male-dominated jobs to consider the possibility that sexism of some form or another is not operating? What level of male under-representation would people need to see in (currently) female-dominated jobs to consider the possibility that sexism of some form or another is operating?

References

1. Del Giudice, M., Booth, T., & Irwing, P. (2012). The distance between Mars and Venus: Measuring global sex differences in personality. PLoS ONE, 7(1), e29265. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029265

2. Geary, D. C. (2021). Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences (3rd ed.). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000181-000

3. Su, R., Rounds, J., & Armstrong, P. I. (2009). Men and things, women and people: A meta-analysis of sex differences in interests. Psychological Bulletin, 135(6), 859–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017364

4. Mac Giolla, E., & Kajonus, P. J. (2018). Sex differences in personality are larger in gender equal countries: Replicating and extending a surprising finding. International Journal of Psychology, 54(6), 705-711. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12529

5. Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2022). Sex differences in adolescents’ occupational aspirations: Variations across time and place. PLoS ONE, 17(1), e0261438. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261438

6. Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2018). The gender-equality paradox in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education. Psychological Science, 29(4), 581-593. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617741719

7. Davis, J. T. M., & Hines, M. (2020). How large are gender differences in toy preferences? A systematic review and meta-analysis of toy preference research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(2), 373-394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01624-7

8. Golombok, S., Rust, J., Zervoulis, K., Croudace, T., Golding, J., & Hines, M. (2008). Developmental trajectories of sex-typed behavior in boys and girls: A longitudinal general population study of children aged 2.5-8 years. Child Development, 79(5), 1583-1593. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01207.x

9. Hassett, J. M., Siebert, E. R., & Wallen, K. (2008). Sex differences in rhesus monkey toy preferences parallel those of children. Hormones and Behavior, 54(3), 359-364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.03.008

10. Alexander, G. M., & Hines, M. (2002). Sex differences in response to children’s toys in nonhuman primates (Cercopithecus aethiops sabaeus). Evolution and Human Behavior, 23(6), 467-479. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-5138(02)00107-1

11. Auyeung, B., Baron-Cohen, S., Ashwin, E., Knickmeyer, R., Taylor, K., Hackett, G., & Hines, M. (2009). Fetal testosterone predicts sexually differentiated childhood behavior in girls and in boys. Psychological Science, 20(2), 144-1488. https://doi.prg/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02279.x

12. Berenbaum, S. A., & Hines, M. (1992). Early androgens Are related to childhood sex-typed toy preferences. Psychological Science, 3(3), 203–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1992.tb00028.x

13. Beltz, A. M., Swanson, J. L., & Berenbaum, S. A. (2011). Gendered occupational interests: Prenatal androgen effects on psychological orientation to Things versus People. Hormones and Behavior, 60(4), 313–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.06.002

14. Cohen-Bendahan, C. C., van de Beek, C., & Berenbaum, S. A. (2005). Prenatal sex hormone effects on child and adult sex-typed behavior: Methods and findings. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 29(2), 353–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.11.004

I’ve always challenged people railing about the ‘women in STEM’ problem to ‘fix’ the other problem of the fact that 95% of primary education graduates are female. All those little boys have no role model and no one who understands their experience and education needs. I wonder what the ADHD diagnosis rates would be if we had a gender parity in classroom education…

Thank you for this very thought-provoking piece. Data are always remarkably revealing. Of course, you are correct in that cognitive models of the world will always set the epistemological structures in terms of which people interpret reality. We also see this in the interpretation of academic performance. For instance: "When ‘Black’ & ‘Hispanic’ Students Outscore ‘Asian’ & ‘White’ Students on the ACT, Nobody Notices" https://everythingisbiology.substack.com/p/when-black-and-hispanic-students ...As a biological psychologist, I'm not sure if one can ever change these fundamental cognitive structures once they are strongly established, not that we shouldn't keep trying! Thank you again. Sincerely, Frederick