This is a second guest post by April Bleske-Rechek, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. You can find her first, and more about her, here. This is an only slightly modified version of a post that appeared at Heterodox Stem.

Anyone who says “words hurt” has never been punched in the face. – Chris Rock, Selective Outrage

Concept Creep and “Harm”

Concept creep refers to the gradual expansion in meaning of harm-related concepts. In the 1980s and since, concepts such as bullying, trauma, prejudice, and abuse have come to include an increasing range of phenomena. The boundaries for harm have expanded to include both direct and indirect behaviors, both physical and verbal behaviors, and both intentionally and unintentionally negative behaviors. The boundaries have also expanded to include both behaviors that cause physical harm as well as behaviors that are subjectively felt to be (or labeled by the receiver as) harmful.

Thus, the concept of harm has broadened. Behaviors and words that are not intended to cause harm can now be considered abusive or prejudiced (or traumatic or harassing or hateful, etc.) if they are perceived as such by the individual on the receiving end, whether they leave a physical mark or not.

College Students’ Attitudes About Free Speech

The research on concept creep is important for understanding college students’ attitudes about free speech. Last fall, colleagues and I surveyed over 10,000 undergraduate students in the University of Wisconsin System. We wanted to explore how students at “typical” public universities (that is, universities other than the East and West coast Ivy League institutions such as Yale and Stanford) think about viewpoint diversity and free expression in their classrooms and on campus. With an average response rate of 12.5% (higher than expected for online survey research with a small incentive), the dataset represents students from all 13 four-year campuses and is broadly representative of the Wisconsin System student body in student level, age, and race/ethnicity. Figure 1 below shows some characteristics of the sample.

What did we find? As a whole, Wisconsin students’ attitudes reflect concept creep: broadened conceptual boundaries for harm-related concepts.

For example, Figure 2 below shows that over a third of students care very little (not at all or a little) about another person’s intent to offend them by expressing offensive views; over a third feel quite a bit or a great deal that people who express offensive views are causing harm to those they offend; and nearly one third feel quite a bit or a great deal that expressing offensive views can be viewed as an act of violence.

Where do these broad concepts of harm come from? Haslam suggested that concept creep is driven by a rising sensitivity to harm and that this rising sensitivity to harm coincides with a “politically liberal moral agenda.” Consistent with that suggestion, there is substantial evidence there has been a societal-level increase in concern about protecting individuals from harm and unfair treatment since the 1980s.

Individuals who have broader concepts of harm tend to be female and identify as politically liberal. These demographic correlates are not surprising: First, females possess a variety of dispositions that evolved in the service of navigating offspring care, such as caregiving tendencies, sensitivity to others’ emotions, and empathy; and in the service of staying alive to provide that care, females have evolved to be more sensitive to pain, threat, and danger compared to males. Second, politically liberal individuals tend to place a heightened priority (relative to other moral foundations that emphasize ingroup loyalty, purity, and respect for authority) on protecting people from harm and unfair treatment when they make moral decisions.

In the Wisconsin free speech data, female students and politically liberal students are more likely to feel that offensive views are harmful and that expressing offensive views can be considered an act of violence. As shown in Figures 3 and 4 below, female students are over twice as likely as male students, and very liberal students are more than five times as likely as somewhat conservative students, to feel that offensive views are harmful and that expressing offensive views can be considered an act of violence. [Notably, other groups of students, such as those majoring in the humanities and those who identify as non-cisgender and non-heterosexual, also tend to hold those views more strongly, but academic area and gender/sexual orientation account for a negligible amount of variance in students’ attitudes after accounting for their sex and political leaning.]

What are the implications of defining harm so broadly? Concept creep is not unambiguously good or bad, and the same could perhaps be said about Wisconsin students’ attitudes about the expression of offensive views. On the positive side, students’ attitudes reflect an important sensitivity to others’ psychological well-being -- a concern for those who may be on the receiving end of negative words and actions that previously went unaddressed and that could be taken as harmful.

On the negative side, however, students’ attitudes may reflect – and reinforce - perceptions of victimhood. When words themselves can be perceived as causing harm, and the judgment of whether harm has been done is in the eye of the beholder, students’ views may reinforce a world divided into victims of harm and perpetrators of harm. Thus, students may perceive one another as victims or perpetrators of harm on the basis of one another’s membership in, or stated support of, a group that is currently suffering or has suffered or been mistreated in the past.

In the context of free speech, the conflation of expressing offensive views with causing harm and violence is in tension with protecting a culture that supports students as they engage – and allow others to engage – with their First Amendment rights. First Amendment jurisprudence does delineate forms of expression that are not protected – such as libel and slander, incitement, and true threats of physical violence – but views perceived by some people as “offensive” or “harmful” are generally a far cry from legally unprotected speech; indeed, sometimes the views perceived by some people as offensive might be more aptly described as uncomfortable truths uncovered by rigorous scientific studies.

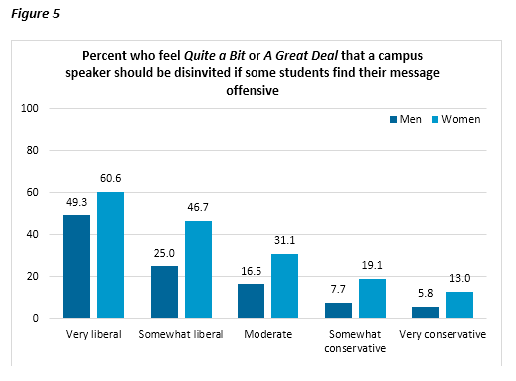

“Harm” and Repression

This tension between creeping notions of harm and free expression is clear: The groups of students who perceive offensive views as harmful or violent also hold the most repressive views about free expression. As shown in Figure 5, female students and politically liberal students are far more likely than male students and conservative students to say that a speaker should be disinvited if some students find the speaker’s message offensive. (There is more detail in the full report; for example, non-cisgender, non-heterosexual, and non-white students also feel more strongly that speakers with offensive views should be disinvited).

These same groups of students are also far more likely to feel that students should report an instructor who says something that some students feel causes harm to vulnerable others. As shown Figure 6, a full 75% of very liberal women (and there are many very liberal women on Wisconsin campuses) feel that students should report an instructor who says something perceived by some individuals as harmful.

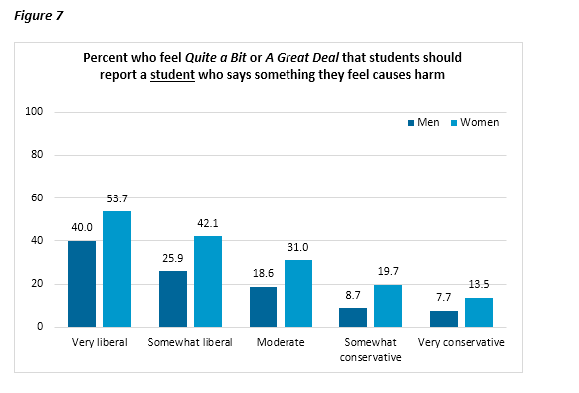

And consistent with what other national surveys have found about students being wary of expressing their views out of concern about how other students will react, the Wisconsin data suggest those concerns are not unfounded. That is, some students feel quite strongly that a student who expresses views perceived as harmful to vulnerable others should be reported.

When “harmful” is defined by its emotional impact -- when one’s emotional reaction to others’ views defines one’s reality – there is no boundary for what can be claimed as causing harm. In consequence, the pool of individuals who perceive themselves as victims of others’ wrongdoing will continue to expand alongside an ever-expanding pool of viewpoints denounced as harmful and thereby worthy of censoring. Indeed, as we have seen play out off campus, in the context of divisive concept (“anti-critical race theory”) bills, both proponents and critics of the bills are motivated by concerns that children are being “harmed” by what they are being told in the classroom.

We seem to be in an untenable position. Although expanded boundaries for harm may be a positive consequence of moral progress, they may also threaten the backbone of universities’ mission to pursue truth: the unfettered exploration, expression, and discussion of diverse ideas and viewpoints.

"indeed, sometimes the views perceived by some people as offensive might be more aptly described as uncomfortable truths uncovered by rigorous scientific studies"

And some may be truths that are blatantly obvious without the need for any sort of study.

It's gaslighting, really.

Reminds me of a quip of Jonathan Rauch:

"Those who claim to be hurt by words must be led to expect nothing as compensation. Otherwise, once they learn they can get something by claiming to be hurt, they will go into the business of being offended."

https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/5539805-those-who-claim-to-be-hurt-by-words-must-be

And of a passage in skeptic Michael Shermer's review of Walsh's documentary:

"But [University of Tennessee professor] Grzanka’s dodge is not uncommon in academia today, and in exasperation with Walsh’s persistent questioning in search of the truth, Grzanka pronounces on camera, 'Getting to the truth is deeply transphobic.' ...."

https://michaelshermer.substack.com/p/what-is-a-woman-anyway

Hard not to see Grzanka's assertion as a suitable epitaph for much of Academia. If "getting to the truth" isn't what Academia is all about then maybe we should burn it to the ground and start over.