The National Institutes of Health recently announced that they are reducing the overhead on grants, which was often 50% or more, to 15%. Here is a tweet summarizing the policy from NIH:

Why You Should Care

Even if you are not a scientist or academic, the U.S. has long been a leader in science and tech innovation. If you want to keep it that way, you might care about how federal policies, in this case the overhead reduction, could affect that. If you are a scientist or academic, well, its obvious and if its not, I discuss it below.

Synonyms: indirect costs, indirects, administrative overhead, overhead.1 You need to know this because academics, including me, use the terms interchangeably. I explain what this is in short order, but first:

The Howling

Academics on X and elsewhere have been screaming Apocalypse! I am not being hyperbolic in describing their … well, are they right and the academic apocalypse is at hand, or are they being hyperbolic? Or am I being hyperbolic by titling this section The Howling? Let’s first see what some are saying. Actually, to keep this succinct, there are only a few examples here, but this seems to capture a very large and loud consensus.

One can find quotes like this in a recent article in the apex journal Science.

From the article:

The reaction from university groups and researchers has been swift and overwhelmingly negative, and some are already arguing the NIH action is illegal.

“This is a surefire way to cripple lifesaving research and innovation,” said a statement from the Council on Governmental Relations (COGR), which tracks federal policy for major universities and medical research centers. “America’s competitors will relish this self-inflicted wound. We urge NIH to rescind this dangerous policy before its harms are felt by Americans.”

Alondra Nelson of the Institute for Advanced Study, former head of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, lamented on BlueSky what she said would amount to a "generational restructuring of the US research and development ecosystem." She added that "This funding shift will not only reduce US research leadership, it will put working people out of work and reduce healthcare access."

An Explainer: What are Grant Indirect Costs?

Scientists apply for federal grants to do research. Sometimes they get them. Let’s say they get a grant for $100,000. This might pay for a lab manager or a student research assistant, animal purchasing and care, equipment, conference travel, journal fees, or any of a zillion other things important for conducting or disseminating the research. Some grants run into the millions, but the amount does not matter with respect to understanding how indirect costs work.

In addition to the work directly related to the grant itself, there are all sorts of ancillary costs incurred by the institution housing the project. Utility bills. Building maintenance. HR, salary, payroll, benefits. Accounting. In some cases for biomed research or some of the physical sciences, there might be special equipment or laboratories that need to be permanent, are paid for by the institution (university, medical school, hospital, etc.) that are going to be used as part of the research, and yet also incur recurring costs. To support this sort of ambient and necessary infrastructure, grant-giving organizations, including the federal govt, provide overhead. Overhead is additional money that comes with the grant to pay for this ambient and necessary infrastructure.

The NIH tweet above shows that, on average, overhead is an additional 35%ish:

9B of the 35B … was used for … “indirect costs.”

35-9=26 = the amount used for “direct costs” — i.e., the actual grant funded research. 9/26~=35%. So the running total indirect cost rate across all of NIH grant giving was about 35%. However, as the NIH tweet shows, it is much higher at some institutions. At Rutgers, it has ranged between about 50% & 65% for a long time and is currently 57%. The indirect cost rate differs at different schools for a variety of reasons. One, but not the only one, is that NIH has recognized that different schools have to spend different amounts for their ambient and necessary infrastructure (cost of living, salaries, property values alone can be massively different in, say, a coastal city than in the rural heartland). Universities negotiate the indirect cost rate with the feds based on $ factors that differ from university to university, which is why we have widely varying indirect cost rates at different universities.

So you can think about it this way: had I received an NIH grant for $100,000 last year, the total amount of the grant would have been $157,000 = $100,000 + 57% of 100,000 = $157,000.

But that is not quite correct. Not all expenditures on grants incur indirect costs. So the indirects on a $100k grant are probably well under $57k even if the indirect rate is 57%. The actual amount can vary widely, but they’d probably be in the 40-50k range, which gets you just under the 35% running average at NIH. Rutgers is a cheap date compared to the Ivies as shown by the NIH tweet at top.

Sidebar: Musk Can’t do Math?

Musk retweeted the NIH tweet that appears at the top of this essay. 9B of 35B is just over 25% of the total. They were not “siphoning off 60% of research award money.”2 I do not know whether he was just careless and flippant, or purposely made an error to make the situation look far worse than it is to justify the draconian cuts he apparently helped institute.

According to ChatGPT, Musk has degrees in physics and economics. Last I looked, you kinda need to be pretty good at math to get either of those degrees.

But now back to our regularly scheduled Academic Apocalypse.

Ambient and Necessary Infrastructure Revisited

Everything I wrote about the ambient and necessary infrastructure is true — but does it justify 50%, 60%, 70% indirect cost rates? Well, maybe sometimes, but let me tell you a story.

I spent 8.5 years chairing three different departments, 7 of those in Psychology. I learned a little about how Rutgers works. First, some context.

Startup Packages for New Faculty

Universities sometimes hire tenured/tenure track faculty. At places like Rutgers, these positions are research-heavy.3 When such faculty are hired, they need to be able to launch their programs of research at their new home. They need equipment, research assistants, supplies, space. They need to be able to pay for participants (human or animal). They need to be able to travel to conferences and pay journal fees. For cutting edge research, launching can easily top $500k; for highly technical research that is common in behavioral neuroscience, it can easily top $1m. These are usually called startup packages. They are very expensive. “Where,” you might be wondering, “does this money come from?” Read on…

A True Story

Once upon a time, in my first term as Psych Chair (2010-13), I had a meeting with my Big Dean.4 We were discussing hiring in Psych for the upcoming year, and part of that discussion was about startup packages.

I asked him where startup package support comes from. He said, “Indirect costs.” I asked, “How does that work?”

He explained that the Central Administration5 keeps some (I think it was about half, maybe a bit less) and then another 40-45%ish goes to the Dean’s Office (he gave me an actual number but I no longer remember it exactly). He also told me that they strive to provide startup packages over the long run that approximately equal the indirect costs brought in by the Department.6 So, administration money generated by the Dept is eventually returned to the Dept, or, at least, the Dean’s share of those are.

This is interesting in light of the Trump/Musk indirect cost reduction. I am pretty sure this was not some sort of money laundering scheme, though it might appear that way on its face. Indirect costs are not supposed to go to other faculty working on stuff unrelated to the grant. They are supposed to go to the ambient and necessary infrastructure that must be paid for in order for the grant-funded research to be viable.

But consider this. Big Dean at Big U gets a Deanly Budget from the Central Administration (hence just “Central”). It pays the bills for running all the departments under Big Dean. Then Dr. Risingstar pulls a big federal grant, say a cool $1m. Overhead at Big U is 60%. This is somewhere around a $500,000 windfall for Big U, and Big Dean’s budget gets, let’s say, $200k of that. And Big Dean or Central takes, let’s say, 100k of that to pay lots of the bills for the ambient and necessary infrastructure that supports Risingstar’s work. That means someone, either Central or Big Dean, has 100k in their original budget that no longer needs to go to pay the bills. Its a windfall. They can take the money that the overhead freed up through its legitimate use and use that freed up money toward the startup costs needed to hire a new faculty member, Dr. Ivy Hotshot.

I cannot say it works exactly this way, because I am not an accountant and I have never seen Central’s or Big Dean’s books (the fiscal type, not the books on Greek history or whatever). One reason that it may not work exactly like this, is that both Central and the Big Dean have reasonable expectations for the flow of federal grant money, and therefore may have figured some expected amount of overhead into the budget. Maybe the full $500k in overhead on Risingstar’s grant is not a windfall, maybe only some of it is. But even if only some of it is a windfall, the analysis still applies.

Its Not Waste, Fraud and Administrative Bloat

Vinay Prasad, a biomed prof at UCSF, has a large social media presence (over 300k followers on X) and a popular podcast.7 According to Google Scholar, he has also managed to publish over 600 papers since 2009, which is about 40/year, which is over 3 per month. I have no clue how anyone does this.8 But I digress.

In this podcast he makes lots of claims, some reasonable, some less so. One that, at least in my experience, is a bit hyperbolic was this one early on:

NIH dollars come with massive indirects which make researchers who have a lot of NIH dollars Untouchable. Universities usually Overlook their errors and keep them on faculty because they get a lot of cash.

Well, most faculty are just about “untouchable” — but that is because of tenure not because of cash. I could say more, but let’s not digress. Vinay continued:

That cash is then laundered by universities given back to them in unrestricted slush funds used for all sorts of purposes including lavish travel and parties and going out for lab meetings. It's wasted. We don't know what happens to all that money.

This is histrionic hyperbole surrounding a few small grains of truth. If someone is throwing lavish indirect cost-fueled parties, I have not been invited. The money is not “laundered,” even though income here can free up money for expenses over there as I just illustrated in my Big Dean Story. In some weird literal sense “We don’t know what happens to all that money” is true — do you know how the indirects on most grants are actually spent? Like, concretely and specifically, not in some handwaving “its spent on infrastructure” way? I certainly don’t and Vinay probably doesn’t. But university grant accountants and managers do, as does the federal gov’t itself:

The oversight infrastructure consists of the following: F&A cost rate reviews and audits (e.g., HHS, ONR, DCAA, and other agency oversight), Offices of Inspectors General audits (e.g., NSF OIG, HHS OIG, etc.), the Government Accountability Office (i.e., studies requested by Congress), agency grant reviews (appraisals by funding agency staff), Internal Audits (performed by institutional staff), and Single Audits (as required by law for any entity expending more than $750,000 in federal funds on an annual basis). Each is discussed in more detail below and contributes to a robust oversight and audit infrastructure that helps ensure effective administration of federal awards and that negotiated F&A cost rates can be relied upon.

The Main Source of Administrative Expansion

I am not saying waste and administrative bloat do not exist. They do. But it is not mostly the fault of indirects. Indirect costs are used for mission-critical research purposes; they are rarely wasted; nor do they contribute to administrative bloat (see Addendum for counterpoint).

State and federal rules, regulations, guidance and policies have gotten insanely complex for everything from harassment to accounting to HR/personnel and probably a lot more that I have missed. Rutgers is unionized, and the contracts have become so complex you need a cadre of administrators just to comply. As chair (of three different departments at three different times over 15ish years) I was almost always grateful for having a few extra administrators who were exceedingly competent at helping me navigate the Byzantine rules that are now imposed on Rutgers. This was especially true for grants management (both my own and those of the faculty in the departments I chaired).

This is a job for DOGE! SOME of those rules and regulations are probably necessary, but lord above, if they could cut the unnecessary ones it would be a boon to all of us. Think “scalpel” not “battle ax.”9

The Academic Trumpocalypse is Here!

The mandated drastic reduction in indirects will be (at least in the short term, more on this below) a disaster for research universities. I wanted to write “unmitigated disaster,” but, as shall be shown below, there are indeed steps they can take to mitigate it.

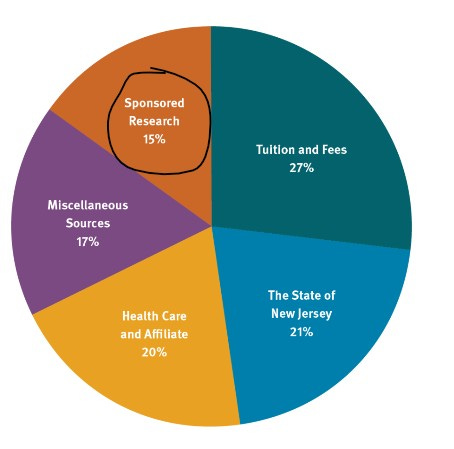

I will walk through why it is a short term disaster using Rutgers as an example because it is what I know best. This chart shows the main sources of Rutgers budget .

“Sponsored research” is grants. They do not break it down further, so I need to make the following assumptions10 to proceed:

Sponsored research means all money from all grants, including those with and without indirect costs (yes, some come without any).

2/3 of the grant dollars are from the federal govt. I pulled this out of my ear, but the feds are the biggest funder by far. The math would change a bit if its half or 75% or even 90% but the fundamental analysis would remain intact.

So 2/3 of the grants at Rutgers had the pre-Trump indirect rate of 57%. But not all grant expenditures incur indirects. At NIH, the running average is 35% of all grant money. Rutgers is slightly lower than the elite U’s, so let’s say the running proportion of federal grants allocated to Rutgers for indirects is 33%.

Making these assumption, 2/3 of the 15% of the income from “sponsored programs” comes from the feds. So that’s 10%. But indirects are 33%, so that’s 3.33% out of the 10% that constitute federal grants to Rutgers. But the whole 3.33% is not eliminated because the Trump/Musk reduction is to 15%, not zero. So let’s call it a 3% reduction. My intuitive interval around this (given uncertainty around my assumptions) is that the real figure is probably 2-4% but, to keep this concrete, let’s stick to 3%. Does not sound like much, right? I mean, if you had to cut your weekly spending by 3%, you’d be fine.

For universities, this is a disaster. I know, because I administered Psychology through two separate horrible budget situations: 1. One in the aftermath of the Great Recession; 2. One during Covid. Both times, there were cuts in the 3-5% range.

The reason it is horrible is that most University costs are fixed. Tenured faculty salaries. Benefits, Utilities. Mortgages or their equivalents. 90% or thereabouts of Rutgers expenditures are fixed costs, and cannot be changed in the short term. I actually think its higher than 90% but let’s call it 90% exactly. 10%, in this scenario, is discretionary. That means a 3% budget cut is a 30% cut to all discretionary spending. And if I underestimate fixed costs, if they are, say, more like 94%, this is a 50% cut to discretionary spending. This means hiring, startup, construction, renovations, department budgets, internal research support, and much more. Cut in half.

“Now,” you might say, “indirects were never supposed to go to those things anyway!” True, but, as I tried to point out under the sections on Ambient and Necessary Infrastructure, money is fungible even when not laundered. If you can pay the utility bills, lab animal caretaker and janitor from indirects, you have money you can direct elsewhere. But now you don’t have most of that money.

All this refers to what I am mostly familiar with — universities. But stand-alone research centers, hospitals, and medical centers also receive grants. Even for medical schools within universities, the funding model can be quite different. Their dependence on indirects may be more extreme, and so the indirect cuts even more apocalyptic.

Happy days are not here again.

Why the Indirect Cost Cut may be Good for Academia

I know. I just wrote a whole section on why The Academic Trumpocalypse is Here. And it might be. But it might not be.

It won’t be easy, or fast, but it may be net good. There will continue to be a lot of screaming during the Trumpocalypse. There will be real pain. But first…

More Money for … Science!

Cutting the indirects means there is more money for the actual science. This is simple 5th grade math. If the NIH budget is 35B, and 9B used to go to indirects, this means 26B goes to the direct costs required to conduct the research. But if indirects are capped at 15%, they will be far less than 9b, probably more like 5-6B. Grant funding goes from 26B to 29B or 30B. Absent Trumpocalypse, this is great news for scientists.

Wait! How Do I Know They Won’t Cut the Indirect Cost Difference?

How do I know they won’t just cut the savings from lowering the indirects to 15% and lower the allocation to NIH, NSF, etc.? The deficit is huge. We have to get closer to balancing the budget. We all have to do our share. Academia, suck it up, you’re not special. That sort of thing.

I don’t know what will happen. However, Congress allocates the budget, not the President. The President has some flexibility in how to allocate the budget within budget categories, but the amount of the budget for specific govt activities (such as NSF and NIH) is determined by Congress. The current budgets of NSF and NIH are fixed unless Congress modifies them. So Trump does not have the authority to cut the NIH or NSF grant budgets.

Now, lots of people are predicting Trump’s administration will flagrantly violate laws to implement its agenda, and maybe they will. Academics tend to argue that almost any policy they do not like is illegal, and, like the boy who cried wolf, they should rarely be believed. And yet:

Something I intermittently find on X is people claiming Trump will go full Andrew Jackson who supposedly said:

[Supreme Court Justice] John Marshall has made his decision. Let him enforce it.11

That is, supposedly, Trump will just ignore court rulings against his administration. Maybe he will ignore the Constitution that gives Congress, not the President, the authority to allocate the budget. However, I have yet to see this happen. In the one instance I am aware of, Trump halted payments on existing federal research grants, a judge ordered those payments to resume, and the Trump administration complied. This was the opposite of “Trump will just ignore the courts.”

So, for now, I have no reason to believe Trump will knowingly and intentionally violate the law. He may forge ahead, law be damned, but if a court rules against him, I predict he will abide by it. Of course, I could be wrong. But by “violate the law” I do not mean some academics’ opinions about the law, I mean court rulings.

In the same spirit, I conclude (till there is reason to believe otherwise) that the reduction in indirect costs inherently produces a rise in federal money available for the direct costs on grants.

Sidebar: Do Musk and Trump Hate Science or Academia?

I have no special insight into their beliefs or attitudes. But paying more for academic science is kinda the opposite of “hating” science or academia. It might be misguided. It might ultimately provide a cure worse than the disease. It might produce the nightmare the critics have predicted. But they have produced more money for scientific research by cutting indirects!

I suspect neither Musk nor Trump particularly care about academics screaming. Not their constituency. But hate us? If they hate us, they would be attempting to strangle funding for academic science. Instead, they raised the proportion of money available for that science.

I mean, who values a car more? Someone willing to pay 20k for it or someone willing to pay 30k? Allocating more money for direct costs is the exact opposite of hating science. It might be misguided and it might not; but it is definitely not hating science.

The federal budget deficit is huge, so cuts may well be coming. To many things. Including us. Only if they make science take a disproportionate hit on funding compared to other discretionary expenditures could one justifiably conclude they “hate” us or want to degrade Amercan academic science.

The Great Academic Reset?

Academia will attempt to adapt to this strange new normal. And it will surely succeed to some degree. And, if it plays its cards right, it might be better in the aftermath:

Here are some possible adaptations:

Put more of the costs for the ambient and necessary infrastructure into the direct costs of the grant. This will recover some of the losses and make the grant expenditure process vastly more transparent. Federal grant agencies that have caps on the amount that can be requested should raise those caps accordingly.

Cut bureaucratic bloat. Even though the indirects did not cause academic bloat, cutting them provides university leadership a golden opportunity to identify its priorities, and streamline accordingly. Bureaucratic bloat should have a target on its back.

Eliminate all DEI bureaucracy. Its an expensive boondoggle at best and actually harmful to core academic intellectual missions at worst. Cut all trainings except those needed to ensure employees understand anti-disrimination and anti-harassment laws and policies. Faculty can still teach courses on prejudice and administrators should enforce anti-discrimination policies. But that has been going on for decades; no DEI bureaucracy needed.

Streamline IRB bureaucracies. IRB overreach has become insane at Rutgers and elsewhere. Cut back all but minimal requirements to ensure participant safety. This means, e.g., that all studies that just involve asking questions should not even require IRB approval, monitoring, or final “reports.” Cut paid staff by half.

Eliminate all strategic planning at the university level. Let the damn deans and departments chart their own futures. Rutgers has an entire VP level office devoted to strategic planning. Two execs plus only the gods know how many support staff. Close it. Let the President and Chancellors decide whether to buy or build new buildings. The End.

When I was chair, I had to fill out all sorts of stupid online forms that, as far as I know, no one paid attention to. Cut all that, reduce the IT staff time devoted to creating/implementing this nonsense, and the effort spent by anyone maintaining records of it.

Allocate funding of department’s operating budget to the department with minimal oversight — just enough to ensure against malfeasance. Cut Dean’s office administrators responsible for “overseeing” and “approving” dept. expenditures.

Incentivize department-level entrepreneurial innovations. If a dept creates new certificate or masters programs, let them keep a significant percentage of the tuition income it generates. This will incentivize ways for departments to generate income streams, which can then be used to replace some of lost indirects.

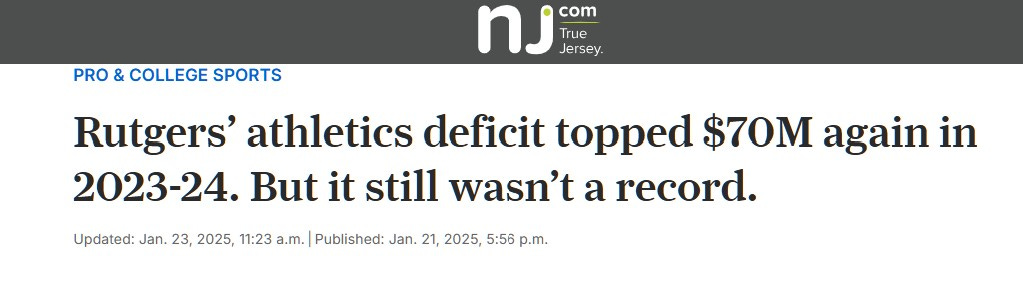

Cut Athletics. This is the pot of gold. Most universities with big football programs lose oodles of money. Not the big ones you know about — Texas, Ohio State, Notre Dame, Alabama, and the like. But the vast majority of the rest.

Here is a Rutgers pie chart of what it spends its money on:

Athletics is 3%. We want some athletics. Recreational athletics is great for students and faculty but pretty much always a money-loser. But if we could extricate ourselves from the insane spending on football, and, to a lesser extent, basketball, that has plagued Rutgers since the 1990s, we could probably save at least 1 of those 3%’s, maybe more. Cut the 70m deficit to even 30m, and that is a lot of ambient and necessary infrastructure that Rutgers could afford.

And these are just the ones I have thought of in the two days since the indirect cost story broke. I would be stunned if, with a little effort, way more could not be found.

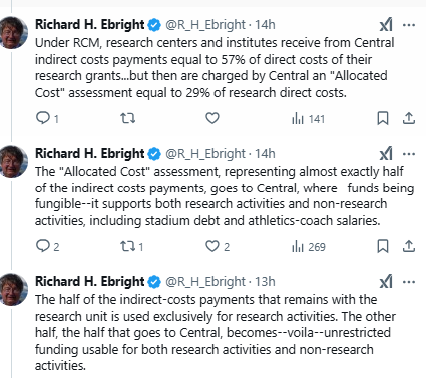

Addendum: Maybe Indirects HAVE Contributed More to Academic Bloat than the Above Suggests

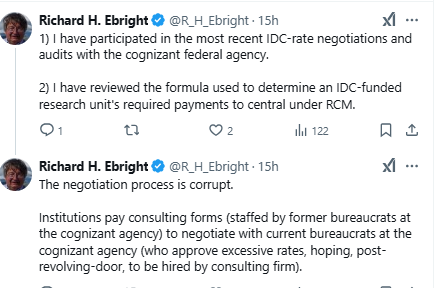

I added this section AFTER posting the rest of this essay because I had a very interesting conversation on X with Rutgers Board of Governor’s (BOG) Professor of Microbiology Richard Ebright. BOG Profs at Rutgers are few and far between and receive that designation for being even more accomplished than mere Distinguished Professors, like me. Accordingly, he had a bit more experience than even I had dealing with grants and indirect. Richard believed I had not been critical enough of the ways in which indirects are used at Rutgers. Here is why.

Let me unpack this. “RCM” is how Rutgers administers its budget. According to Richard, above, academic centers and institutes receive all of their indirects, but then the administration charges them an amount equal to half of that and takes it back (they receive the full 57% of indirects but then have to give half, or 29% back to the administration). I do not know if this is illegal laundering. Probably not, because this is, according to Richard, done completely above board, which means the govt auditors know all about it. Still, it fits my definition of legal laundering, because once the money is returned to the administration it is no longer “from” the granting agency. That would seem to mean that the Rutgers administration can spend the money on pretty much anything it likes, freeing up the administration to spend it on pet projects, creating a DEI bureaucracy, or subsidizing the fiscal black hole that is Rutgers athletics.

This is NOT the system by which departments receive indirects. Departments at Rutgers have never received half of their indirects (it has ranged from 0 to about 20% over the years). But the centers and institutes typically obtain a disproportionate amount of the federal grants received at Rutgers. How much? I do not know. Regardless, this might contribute to bureaucratic bloat, but, more important, it contributes to general bloat, even when it is not bureaucratic, because it appears to become unconstrained money that administrators can use as they see fit, including for lots of purposes unrelated to research.

And just when you thought it could not get worse:

I have never participated in such negotiations and cannot independently verify what Richard is claiming here. It does, however, sound a lot like how academia and govt and consultants usually do business.

But even Richard reached this ultimate conclusion:

Conclusion

I do not know whether the indirect rate cut will ultimately prove the disaster predicted by almost everyone in academia. It might. Or, it might inspire greater transparency and a much-needed (in my opinion) reconsideration of academic priorities that leaves the research mission intact or even stronger.

For those concerned about equity, the flat 15% will contribute to it. Why? Most of the elite coastal universities are in very expensive areas. 15% will go much further at Iowa State University than it will at Harvard, Stanford, or Rutgers. This means it will be easier for universities in less wealthy areas to adapt to the new indirect rate. I do not know if this is good but it seems likely to be true. For those who care about this sort of equity, this should be a net plus. Of course, this would be true of any flat rate, including (what are probably more reasonable) ones such as 20 or 25 or 30%.

I am rooting for administrators to reconsider their fiscal priorities and refocus academia on its main missions: teaching, research, and, to some extent, service to the wider world. But I am not particularly confident that administrative leadership will have the vision or values necessary to pull it off. Absent that, we may well be on the road to ruin.

A Strange Ray of Hope

DOGE is about cutting the bureaucracy and making things more efficient. I have a proposal for DOGE that works with instead of aganst them:12

Keep the 15% indirect rate13 BUT

Apply it to EVERYTHING in the grant.

This would do several things:

It would INCREASE the amount of indirects above the Spartan level everyone assumes, because, in the old system, indirects only applied to some grant expenditures. Apply 15% to ALL expenditures and it will produce more indirects than only applying them to SOME expenditures.

It would MASSIVELY simplify the grant budgeting process. Just propose a total, say, 100k, and the indirects are 15k. No having a bazillion rules about what is and is not covered, a bazillion bureaucrats fiddling with this, and a bazillion university grants accountants running complex spreadsheets because indirects apply to THESE expenditures but NOT those expenditures.

Reduce administrative bloat, because neither the govt nor universities will need all those bureaucrats and accountants to figure out and monitor the computation of indirects. Replace them all with one moderately competent 5th grader, who can figure out 15% of 500,000.

Commenting

Before commenting, please review my commenting guidelines. They will prevent your comments from being deleted. Here are the core ideas:

Don’t attack or insult the author or other commenters.

Stay relevant to the post.

Keep it short.

Do not dominate a comment thread.

Do not mindread, its a loser’s game.

Don’t tell me how to run Unsafe Science or what to post. (Guest essays are welcome and inquiries about doing one should be submitted by email).

Special Commenting Request

If you have been a dean or chair or have had large federal grants, and your experience is very different than what I described here, please do provide a comment describing that experience. I do realize that not every place is the same or like Rutgers.

Footnotes

Synonyms for indirect costs also sometimes include “F&A” which stands for facilities and administrative costs. I don’t use that term here, but if you see it in the wild, it means the same thing.

Siphoning off 60%. “Siphoning off” implies something like accounting malfeasance for irrelevant and probably self-interested purposes. Even if the prior system needed reform, this strikes me as an unjustifiably dismissive sneer, in addition to being mathematically inaccurate.

Research heavy faculty. Don’t get me wrong. Teaching is important for these faculty as well, its just not the topic of this essay. From my vantage point of being at Rutgers a looong time and chairing 3 departments, the research active faculty tend to be generally excellent teachers, and among the best.

Big Dean. Rutgers is gigantic. It has lots of little deans. Most of my interactions as chair were with the little dean (aka “associate dean”) for the social sciences. The Big Dean is the UberDean (not Uber as in Lyft, but Uber as in Above and Beyond). Little deans answer to the Big Dean.

Central Administration. Presidents, VPs, Provosts, Chancellors. That general ilk. I mean, they don’t pocket the money. They spend it on stuff, presumably stuff that they think the U really needs. Like a football team. Ok, I am just being snarky. Maybe half-snarky. Athletics at Rutgers runs a large deficit, disproportionately from football. The money has to come from somewhere. I doubt it is from laundering indirect costs, at least not directly. But if there is more money here and less money there, the here that has more money can pay certain expenses that free up money that can be used over there. Of course, I am not an accountant, so you should take this analysis with a full box of salt.

Big Dean tells me that startup costs roughly equal the indirect costs brought in by the Department. I think this was true for departments that routinely received federal grants. Faculty in other departments (e.g., humanities) also receive startup packages or something like it. On one hand, faculty in those departments typically require much smaller packages to get started. On the other, faculty in those departments rarely obtain grants with overhead. So their startup packages, though much smaller than that of those in Psychology (and, I suspect, biomed, physics, chemistry, etc.), cannot usually come from the overhead generated by grants obtained by faculty in that department, because those faculty rarely obtain large grants with overhead. The money has to come from somewhere. I can’t say for sure that, even indirectly, that money comes from the grant overhead costs generated by other departments. I am pretty sure, though, the more overhead generated by grant-getting departments doesn’t hurt the ability of the administration to provide startup to new faculty in departments where few, if any, faculty obtain federal grants.

Vinay Prasad. I thank one of my X followers and regular interactants, Jan Brauner, for directing me to this video.

I have no idea how anyone publishes 600ish papers in 15 years. That’s 3 papers every four weeks-ish. Literally, no idea. I’d have to watch someone do it to begin to have an understanding. I am actually vaguely suspicious of anyone who cranks out stuff that fast, because how can you do most of it carefully? But maybe there is a good answer to that question. Regardless, it takes me on average about 3 years from idea to publication to publish most empirical papers. Say a year for chapters. And I can juggle 10-15 projects at a time, prioritizing 2-3 and only intermittently working on the others. Sometimes, I have excellent collaborators who take the lead and shoulder disproportionate effort. That’s how I get to publishing 150ish articles and chapters, and 10 books in 40ish years, including grad school. Had I played less tennis, had a smaller family, fewer cats, or more aggressively sought grants to build an empire, maybe you could add another 50-100 articles and chapters, and another book or two. I am so glad I did all those things besides work. Still, had I not, maybe, on the outside,I would now have 250 publications. But that would still be in 40 years. I’ll blame it on the cats.

Administrative bloat resulting from govt rules. I thank Jim Coan for reminding me of this on X.

Rutgers budget assumptions. If any are wrong, they will likely mean my analysis is considerably off.

Marshall and Jackson. The quote is apocryphal, but Jackson absolutely did refuse to obey a Supreme Court ruling, so the spirit is on target.

Apply the 15% to the whole grant. Alex Stewart first suggested this to me on X.

DOGE, keep the indirect rate at 15% but have it apply to all grant expenses. Actually, a rate of 20-25% probably has considerably less potential to produce catastrophe. And though the current system of the feds negotiating with each U seems insanely complicated, they could do something like vary the rate by region and/or rural/urban locale. Still, a flat 15% applied to everything seems like an improvement over the policy initiated under Trump.

2/10/25 update. Based on conversations on X with Jim Coan and Richard Ebright, I have added two new sections to this post. They are titled:

The Main Source of Administrative Expansion

and

Addendum: Maybe Indirects HAVE Contributed More to Academic Bloat than the Above Suggests

I am a dept. chair, working with a modest mof-level dean, as an associate dean (some of might say ass. dean with justification). I am a PI on federal, state, and foundation projects. The whole economy of health science divisions of universities are fully dependent upon the acquisition and management of these facilities and administrative (F&A) payments I think to do this with existing federal awards, NIH is going to have to go the full Jackson, because the federal government, HHS, has negotiated all these rates in formal agreements into the future with each institution and have indicated which awards they apply to at the time of funding. Other parts of the federal government already indirect costs to 8%,15%, or other rates. I had colleagues in oncolcogy say their indirect costs are actually 85% or so. Mine, in mental health and rehabilitation are significantly lower.

NIH indirect money is greener than all others (as in greenbacks, not climate), because it is additional money. For other grants, indirects come out of the total cost of the grants. If the rate is 57%, when you are awarded $100,000 by NIH, that gets your institution another $57,000 for a total of $157K. But if you get money from the lowly National Institute of Disability Independent Living Research (NIDILRR), to pay the full indirect costs of a $100,000 projects you actually only wind up with $63,700, because 57% of that, $36,300 goes to direct costs, expending the entire $100,000. The very high rate makes for perverse incentives, such as making it unappealing to submit proposals, and odd policies at some institutions of charging indirect costs back to units that don;t get the full rate on successful applications. Selfishly I am rooting for lower F&A rates, to stop disincentivizing our faculty from making applications where high rates are directly eating into the direct costs of our non- NIH projects.

I agree if the overall funding and priorities are retained (which seems like a big if) it is a better solution that indirect cost rates are lowered (but not by this abrupt method) and have the projects document their actual costs as they vary by project, as we have to do with some state-funded projects now. This is pretty much anathema in the academic land I reside, so check back to see if I retain those dubious titles in the future.