This entry is a reposting of the announcement that appears on the American Enterprise Institute’s website. They are hosting the online book event (register here if interested in attending live or virtually) and they are publishing the book. Lee

Key Points

Free inquiry is essential for democracy, science, and individual justice.

Free inquiry in the United States is under threat.

Today’s taboos are developed and enforced not by outsiders but students, professors, and bureaucracies within higher education.

Rapid, ongoing changes in higher education bear close examination with regard to their influence on free inquiry in academia.

Introduction

For more than a decade, college campuses have severely restricted free speech and free inquiry in ways not seen even in the McCarthy period. The contributing authors to The Free Inquiry Papers explain how this happened, why free inquiry matters, and most importantly, what individuals, policymakers, and institutions can do to change course.

The authors establish three foundations.

First, free inquiry is essential for democracy, science, and individual justice. It is part of an institutional and attitudinal system, what Jonathan Rauch refers to in Chapter 19 and his important book as “the constitution of knowledge.” Free inquiry enabled modernity.

Second, free inquiry in the United States is under threat, as Joseph L. Sutherland and James L. Gibson show in Chapter 5 (“The Rise of Self-Censorship in America”). Increasingly, people fear saying what they think, and scientists are told what they can and cannot study. We have forgotten the lessons of US history, as Jonathan Zimmerman discusses in Chapter 3 (“Why Free Speech?”), and the deadly lessons provided in the Soviet Union and China, as detailed by Catherine Salmon and Lee Jussim in Chapter 9 (“Lysenkoism Then and Now”) and Anna I. Krylov and Jay Tanzman in Chapter 17 (“Fighting the Good Fight in an Age of Unreason”).

The success of denunciation and demonization by social media mobs has incentivized a whole generation to attempt to impose new norms, values, and rules on others, as detailed in Chapters 7 (“Academic Freedom and the Social Media Veto”) and 10 (“Ostrich Syndrome and Campus Free Expression”). As a result, previous norms, values, and rules have changed quickly—and not for the better. Even this book was affected. Two acquisitions editors at prominent scholarly presses passed on it, fearing controversy. Three authors pulled out of the project, for fear of how their academic employers or prospective employers might respond.

Third, today’s taboos are developed and enforced not by outsiders but students, professors, and bureaucracies within higher education. Indeed, the steady growth in censorious bureaucracies and social media exerted a chilling effect on speech and inquiry, likely causing local and regional suppression of free thought. Threats to free inquiry increasingly affect the business, academic, and even scientific sectors, including medicine and medical schools. This affects us all, as Sally Satel shows in Chapter 8 (“Do No Anti-Racist Harm: Medical Education Under Threat”).

The editors of The Free Inquiry Papers then distill the book’s recommendations into short-term and medium-term actions and tactics for legislators, alumni, and higher education leaders that can enable long-term reforms. The good news is that our society and higher education system remain largely free. As Krylov and Tanzman point out in Chapter 17, restoring free inquiry here is almost infinitely easier than the work of Soviet dissidents confronting communism. To those who despair, our first admonition is to have hope! Hope enables agency. Agency enables action.

Short-Term and Medium-Term Efforts

Sponsor Campus Debates on Contentious Topics

State legislators and others should encourage and possibly fund campus debates on a broad array of issues and, most importantly for our purposes, diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) practices. These often oppose free inquiry and have become deeply entrenched in universities. Campus debates are rare, as George R. La Noue documents in Chapter 14 (“Can Intellectual Diversity Be Recovered in Academia?”). To its credit, however, Florida now requires public campuses to hold debates.

We also recommend developing a national database of debates and debate cancellations, created by a free speech nonprofit such as the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE). To draw attention to the issue, one could expand existing FIRE polls to measure the degree to which secondary and college students are exposed to debates at their educational institutions. If at many institutions the result is rarely or never, then we need to ask whether such institutions should receive public funding from our ideologically diverse taxpayers.

Humanize the Canceled

FIRE or a similar organization should publicize the stories of those who have been canceled, perhaps using YouTube or other social media to introduce the victims. This could include historic free speech activists like the still-active Mary Beth Tinker of Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, noted in Zimmerman’s chapter. Too many of these figures have been dehumanized, enabling others to ignore their plight. Telling their stories is a necessary counterbalance to attempts at demonization and social ostracism.

Hold Hearings on Bureaucratic Attempts to Limit Free Speech and Open Inquiry

There is another important tool that can bring transparency. State legislatures and Congress should hold hearings to highlight attempts by university bureaucrats (sometimes in collaboration with the media and Big Tech) and higher education leaders to limit free speech. Such hearings could personalize university administrators’ roles in producing censorious norms and practices, ideally leading to demotions in some cases, thus offering bureaucrats incentives to avoid bad behavior. Such hearings can work, as we learned when the presidents of Harvard, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the University of Pennsylvania faced congressional scrutiny for rife antisemitism on their campuses. This led to the eventual resignations of two presidents. All three of these institutions also had a poor record of defending faculty who voiced what some might consider controversial statements.

Given the tendencies of higher education bureaucrats, congressional hearings could be a crucial step in making bullying and censorship riskier than allowing free inquiry by exposing institutional hypocrisy. This could motivate governing boards to demote administrators, including college presidents, who use their bureaucratic power to limit rather than safeguard free speech and free inquiry rights (or who simply fail to do so when they could have). The terminations of just a few higher education leaders could send a message throughout the industry, reshaping culture.

Repair or Reduce Higher Education Bureaucracies That Limit Free Speech

Higher education bureaucracies should be reformed and downsized. Stand-alone DEI bureaucracies have grown exponentially and expanded their missions in ways detrimental to free inquiry.

They should be replaced with smaller free inquiry bureaucracies, which would educate students and professors on the importance of free speech during orientation. Such bureaucracies should strongly encourage departments and whole institutions to develop their own versions of the University of Chicago free speech principles and the Kalven Report on maintaining institutional neutrality (discussed in Chapter 6, by Aaron Saiger) and to otherwise embrace the merit, fairness, and equality principles outlined in Chapter 15 by Dorian S. Abbot, Iván Marinovic, and Carlos M. Carvalho.

Teach Free Speech and Open Inquiry

Colleges and universities should require a foundational course on free speech and open inquiry and support faculty training in this area. State legislatures could strongly encourage colleges to require an introductory class on free speech and free inquiry to help students adjust to college life, perhaps modeled on the University of Wisconsin’s First Amendment class, as Donald Alexander Downs describes in Chapter 12 (“Mobilization for Academic Free Speech: The Wisconsin Model”).

Relatedly, colleges could sponsor student and faculty training in free speech activism. These could help counter the thousands of courses, often in education schools, that teach students how to limit free speech and free inquiry. Free speech courses could be fairly inexpensive if many components were online as in most existing training, including (demonstrably ineffective) diversity training.

End Public Funding for Higher Education Organizations That Require Political or Ideological Statements of Faith or Particular Racial Identities

Three other steps would rest on federal or state legislation. Governments should deny public funds to higher education institutions that require political or ideological statements of faith, such as DEI statements, for job applicants or employees seeking promotion (with certain exemptions for faith-based institutions). Journals that have such barriers limiting submissions should lose federal funding if they have it. For example, a journal editor recently told one of us (Robert Maranto) that he was not allowed to submit quantitative research on black school principals because the author was not himself black.

Add Ideology to the List of “Protected Classes”

Another step would be to add ideology to the list of “protected classes” in admissions and personnel systems to restore some pluralism to academic institutions and departments that skew heavily left. Unlike ideological monocultures, pluralism is directly related to open inquiry because it widens the universe of ideas acceptable for study and consideration.

Because surveys consistently show that roughly equal proportions of people identify as Democrats and Republicans, with far more identifying as moderates and conservatives than as liberals, most academic institutions would fail a “disparate impact” test applied to political identities. Disparate impact tests measure whether hiring or other practices disproportionately affect a protected group. Although passing such a test is not sufficient to prove discrimination, it is a first step. Thus, this could motivate lawsuit-averse administrators to adopt procedures designed to increase pluralism in their institutions. This would also encourage the creation of specialized law firms, privatizing some of the regulatory efforts to encourage free speech and free inquiry. This suggestion, however, is open to objection on the grounds that it feeds group-based approaches.

Evaluate DEI Interventions

Many attempts to regulate speech and inquiry reflect critical-theory-oriented efforts to enhance equity, in part by improving class mobility. Unfortunately, many widely used practices simply fail to work. Accordingly, we propose that the National Science Foundation enlist researchers from across the ideological spectrum who have publicly stated widely different views about the value of DEI programs to issue a report on the effectiveness of DEI-related interventions in improving class mobility and intergroup relations.

Fight Bad Speech with Counter-Speech

Likewise, the best way to defeat widespread support for Hamas on elite college campuses is not to criminalize such speech and make its proponents martyrs but confront it with factual and at times satirical counter-speech. Why should the The Babylon Bee have all the fun? Over the long term, this could decrease the use of ineffective and censorious practices, helping safeguard free inquiry. It could also demonstrate the effective use of empirical work (and frivolity) to change public and social practice.

Reform Institutional Review Boards

Institutional review boards (IRBs) were created to protect human subjects in research, particularly in light of failures to do so, such as in the Tuskegee syphilis study. However, participating in most social science research does not present legitimate threats to physical or mental health. Increasingly, IRBs are limiting research, not for their intended purpose of protecting subjects but for ideological reasons—they simply disapprove of the question being studied. Accordingly, Congress should remove most social science from IRB jurisdiction.

Long-Term Institutional Reforms

Improve General Public Education on Pluralism and the First Amendment

To paraphrase James Madison, laws and even constitutions are mere paper barriers without public support. Unfortunately, considerable evidence indicates that among elites, these values are fading fast—a potentially calamitous development.

To counter this, our most important long-term reforms would remake K–12 education standards and curricula to highlight pluralism and the First Amendment. We must do more, pushing public education to address why 20th-century fascist and communist alternatives did not merely fail but failed with disastrous consequences for humanity.

Relatedly, Congress and the president should declare November 9 (the anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall) a national holiday marking the end of the Cold War, to facilitate teaching about how Marxism failed in 20-odd countries. Indeed, “Fall of the Wall Day” could be paired with Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Juneteenth, and July 4 as one of four Freedom Day holidays. This would provide historical references so students might see how new higher education institutions such as bias-response teams resemble communist institutions like the Stasi in the German Democratic Republic (i.e., Communist East Germany).

Create New Institutions of Higher Learning

On the higher education front, an additional possibility, albeit a resource-intensive one, would be to establish new institutions dedicated to the robust exploration of ideas and the search for truth. An example of this is the recently established University of Austin, which was flooded with job applications as soon as plans for it were announced. Given the infrastructure of a research university, creating several satellite campuses for the University of Austin would be more cost-effective than creating brand-new universities.

A less costly option would be for public university systems to dedicate some of their campuses entirely to the classically liberal values of merit-based admissions and hiring. These distinct institutions would need distinct accreditors.

Such education markets would then enable students, faculty, and donors to vote with their feet and dollars. Ultimately, through their choice of practitioners, the public can decide which type of institutions should train the new generations of doctors, lawyers, scientists, professors, educators, journalists, and citizens.

Individual and Collective Action

While much of what we say concerns policymakers and institutions, we end this summary where we began it, with a plea for individual agency and collective action. We urge those whose freedoms are threatened to band together with others, as professors recently did at Harvard, for both their sanity and their long-term success. Without emotional and material support, as well as friendly advice, organized censors will pick us off one at a time. Indeed, the social isolation produced by the COVID-19 pandemic enabled such bureaucratic behavior at campuses like Stanford, where administrators closed many student organizations and forced others to endorse DEI principles, ultimately undermining social trust in the manner of all totalitarian regimes.

History rarely moves in straight lines—it is not too late to change direction. The current antipathy toward free inquiry can, and must, be changed for both education and democracy to thrive.

About the Authors

Robert Maranto is a political scientist serving as the 21st Century Chair in Leadership in the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas. He researches administrative reform generally and education reform in particular while editing the Journal of School Choice.

Lee Jussim is a distinguished professor of psychology at Rutgers University, where he recently completed his second term as department chair and is currently serving as acting chair for the anthropology department. He has published over 100 articles and chapters and seven books.

Catherine Salmon is a professor in the psychology department and the director of the human-animal studies program at the University of Redlands. She is the coauthor of The Secret Power of Middle Children (2012) and Warrior Lovers: Erotic Fiction, Evolution and Female Sexuality (2003).

Sally Satel is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute; the medical director of a local methadone clinic in Washington, DC; and a lecturer at Yale University School of Medicine.

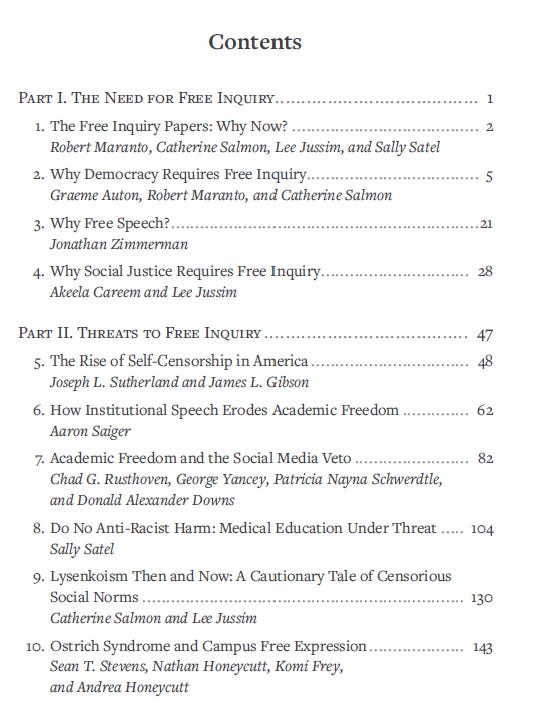

That ends the AEI announcement. Here is the book’s Table of Contents:

One note: The chapters were written and revised 2022-2024, before the Trump administration took office. Speaking for myself only, if we were to do a sequel, there probably would be chapters on how and whether Trump’s policies are more of a threat to free inquiry or more of a solution to the types of problems emphasized in this book. Indeed, my chapter with Akeela Careem, on Why Social Justice Needs Free Inquiry, pointed out that there is a long intellectual, political, and legal history that includes Frederick Douglas and Thurgood Marshall, demonstrating that free speech and free inquiry are foundations of social justice. We also pointed out that there is a long and ugly history showing that if you begin to erode those protections, as have many academics over the last 15 years, you do so at the risk of creating new censorious norms. And if you do that, when power shifts, censoriousness is likely to come back to bite you.

This exchange (found here) between Alice Dreger (author of, most famously, Galileo’s Middle Finger) and Ivan Oransky (who founded and runs Retraction Watch) nails it:

ALICE DREGER: As you and I both know from our work, there have been plenty of attempts from the left to censor, silence, and punish researchers working on gender and sex issues (example; example; example; example; example; we could go on and on). What would you say to those on the left who decry what we’re now seeing happening at the CDC and elsewhere with this administration in terms of research and other forms of scholarly work?

IVAN ORANSKY: First, I’d decry this censorship myself. It will cause harm, as I’ve noted. But then I’d ask people to do something that may make many of them uncomfortable, which is to consider whether efforts to block discussion of research that are deemed by some to cause harm make it easier for Trump administration officials to justify this kind of censorship. Put another way, how different are these approaches, really? Once we decide censorship is acceptable because the ends justify the means, anyone can use that rationale. If one group weaponizes retractions to delegitimize studies they find problematic, why shouldn’t another?

The censoriousness of social justice academics has come back to bite them, with a vengeance. I should take a side job foretelling the future…

I have explained why I think some of Trump’s policies are indeed a threat to free speech and free inquiry elsewhere (such as here and here) but there is a lot more that could be said — and I am singularly disinterested in making Unsafe Science All Trump All the Time. Still, The Free Inquiry Papers could be quasi-justifiably criticized for ignoring Trump’s policies. It is true that we did not address them, but its not because we ignored them; we wrote the book before he took office.

Commenting

Before commenting, please review my commenting guidelines. They will prevent your comments from being deleted. Here are the core ideas:

Don’t attack or insult the author or other commenters.

Stay relevant to the post.

Keep it short.

Do not dominate a comment thread.

Do not mindread, its a loser’s game.

Don’t tell me how to run Unsafe Science or what to post. (Guest essays are welcome and inquiries about doing one should be submitted by email).

an excellent article. Here's an observation and a question. you correctly point out that people should encourage campus debates on contentious issues. Totally agree and that would be awesome. My observation is that what occurs though is that "controversial" speakers often have a campaign directed at them well ahead of the planned appearance in order to demonize them and create agitation. This occurs with flyers with things taken out of context, and often out of context at best and dishonest critiques at worst. These are the tools used to drive the emotion and create the censorious mob that later interrupts this protests.

How can the schools take action against this? Seems like they need to either have extreme penalties (like suspension?) for interrupting a speaker or something extreme (like expulsion for pulling a fire alarm to interrupt a speaker).

Because otherwise it is asymmetrical warfare and these tactics will continue to be tolerated wink wink nudge nudge by administrators and this will continue to result in a narrow list of "acceptable" campus speakers.

Everyone who says they are "progressive" will also say they believe in free speech and yet they will also deploy these tactics.

What can schools do to change this culture? seems like many steps are required to change the culture to make this happen. curious how you would propose fixing this...

Lee, there are some good ideas here, a few bad ones, and a few that should be added:

1. Supporting scholars who have been deplatformed/cancelled needs to be made a priority. The best way to do this is to create a website/data base like FIRE's where their censored work either as a poster, paper or recorded talk is not only made available to all, but is specifically highlighted for discussion. This would disincentivize cancel cultures attempts and insure that heterodox ideas are not lost.

2. Scholars/institutions that engage in cancel culture should be called out and identified by name and subject to a boycott of invitations/presentations etc. for a period lasting 3 times the length of their own efforts to cancel other scholars.

3. The 4 holidays idea is flawed as Juneteenth is an artificial holiday with no actual freedom merit to it. Native Americans, as sovereign nations, continued to hold slaves after Juneteenth.

Hope this helps!