New Vindication for the Regnerus Same-Sex Parenting Study

Widely denounced study holds up well under rigorous robustness analyses

Lee here. First, an introduction.

This article first appeared in Public Discourse. It is reprinted here with both their and the author’s permission. Dr. Paul Sullins, Ph.D., the author, is Professor of Sociology (Retired) at the Catholic University of America and Senior Research Associate of the Ruth Institute (www.ruthinstitute.org). He has written four books and over 150 scientific journal articles, book chapters and research reports on issues of sexuality, family and culture, among which are "Absence of Harm following Failed Sexual Orientation Change Efforts (SOCE)”, “SOCE Reduces Suicide: Correcting a False Research Narrative”, and “The (evidential) Case for Mom and Dad”, all available online at no charge via Pubmed or SSRN (http://ssrn.com/author=2097328). Formerly Episcopalian, Dr. Sullins is a married Catholic priest; he and his wife Patricia have an inter-racial family of three children, two adopted.

His latest article, the republication of a study retracted for ideological reasons, is forthcoming in the Journal of Open Inquiry in the Behavioral Sciences. Currently readable at

Sullins, D. & Rosik, C. (2024). Perceived Efficacy and Risk of Sexual Orientation Change Efforts (SOCE): Evidence from a US Sample of 125 Male Participants. Researchers.One. https://researchers.one/articles/24.09.00002v4

Art and graphics did not appear in the original; I added them.

by D. Paul Sullins

Recently a statistical critique by Cornell sociologists Cristobal Young and Erin Cumberworth examined how small, invisible methodological choices, such as how categories are classified or extreme cases are handled, yielded very different results in published studies. They did this by examining the results of every possible reasonable permutation of such choices—what they called, with a nod to Spiderman, the “multiverse of analyses”—to show where on the range of possible outcomes landed the outcome reported. This procedure shone a bright light on exaggeration or bias due to hidden analytical decisions.

To demonstrate the new method, they looked particularly at highly disputed studies. Most fared poorly under such scrutiny. For example, for a study purporting to show that men’s income exceeded women’s by 115 percentage points after marital separation, the multiverse of alternative analyses could find at most a gap of only 37 percent. A disputed study reporting that women’s political views cycled from more liberal to more conservative in tandem with their ovulation cycle, they found, had “presented the most extreme estimate available from the multiverse of [120] possible results,” 115 of which showed no effect. To reach such a result, Young and Cumberworth observed, “seemingly every possible processing choice was made in favor of the authors’ preferred result”—indicating extreme bias that undermined the result.

As a kind of stress test, the authors devoted a chapter to reexamining the “now infamous” 2012 study by University of Texas (Austin) sociologist Mark Regnerus which “found that the children of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) parents, compared to those raised in ‘intact biological families’ (IBFs), were worse off in many sociodevelopmental ways”—which they succinctly term the “LGBT effect” (though inaccurately: transgender persons (T) were not studied). The widespread critique of this highly disputed study resulted in a multiverse of more than two million alternative analyses that were statistically significant (meaning the results could not be the result of chance variation due to random sampling). Initially anticipating that “a comprehensive multiverse analysis would drive [the study’s many critics’] point home in a powerfully conclusive way,” Young and Cumberworth instead found something unexpected and remarkable: not one of the two million significant alternatives resulted in positive outcomes for LGBT-parented children. Although often with smaller effects, every analysis confirmed the Regnerus study’s central finding that children turned out better with intact biological parents than with LGBT parents. Regnerus’s thesis, it turns out, was not only true in the analytic model in which he presented it: it was true in every analytic model possible.

To better grasp the significance of this development we need to recall the history and reaction to Regnerus’s study. Until about thirty years ago a longstanding social science consensus held that, compared to other family arrangements, children were most likely to thrive when raised until adulthood by their natural mother and father. Children raised by single parents, subject to the disruptions of parental divorce, or even by adoptive or one or more stepparents, had long been shown to suffer a range of poorer outcomes in emotional health, forming relationships, educational attainment, employment, and more. Then came the by now well-documented capture of social science by left-wing ideologies promoting the removal of social constraints on sexual expression, including freely available contraception and abortion, recreational sex outside marriage, casual cohabitation, easy divorce, destigmatized pornography use, and gay parenting and marriage.

In a pattern now familiar from other culture war issues, the social science journals became flooded with weak, misleading “studies,” often written by politically motivated gay authors, purporting to show that children fared just as well with same-sex parents as with other-sex ones. A primary tactic was to ask obviously biased samples of gay parents recruited from gay bookstores, advertisements in gay-themed newspapers, pride events, and similar sources, how their children were doing, then treat this a representative of all gay-parented children. Rarely were the children themselves examined or even consulted. The “studies” also typically drew samples too small to show any differences between gay-parented and other children even if they existed, then misstated their failure to find differences as a strong conclusion that none existed. One review counted that of the forty-seven studies of gay parenting before 2010, only four used a random sample, and most sample sizes of gay-parented children were fewer than fifty. In study after study, absence of evidence was presented as evidence of absence, feeding a growing consensus, despite the lack of real evidence, that there were “no differences” that mattered for the wellbeing of children raised by same-sex parents and those raised by their own mother and father.

Regnerus’s plan to settle the question was forthright if laborious: he would collect a representative survey sample of persons raised by same-sex parents with enough cases to reveal differences if they existed. Called the New Family Structures Study (NFSS), it screened 15,000 young adults ages eighteen to thirty-nine, contacted at random to collect enough who had been raised by same-sex parents to be able to make meaningful comparisons between them and persons who had grown up with stably married biological parents. The result was a sample of just under 3,000 individuals that included 248 people raised by same-sex parents, by far the largest set of primary, statistically representative data on such individuals yet collected.

Examining this powerful set of data, Regnerus reported “numerous, consistent differences” that disadvantaged same-sex-parented persons. Compared on forty outcomes to persons raised by stable biological parents, persons raised by lesbians differed on twenty-five of them (63 percent), those by gay males on eleven (28 percent). The lesbian-parented children suffered higher depression, lower physical health, and lower income and educational progress. They were also more often unemployed or on public assistance and more likely to have been arrested and to have pleaded guilty to a serious crime. They were much more likely to have been sexually abused as children, to have had an affair while married or cohabiting, and to report that their current relationship was in trouble.

Regnerus did not mince words about the implications of these findings, declaring: “the empirical claim that no notable differences exist must go.” Unlike the NFSS, he asserted, studies focusing on parenting ability or parent reports of current child well-being “will fail to reveal—because they have not measured it—how their children fare as adults.” Further: “The small or nonprobability samples so often relied upon in nearly all previous studies have very likely underestimated the number and magnitude of real differences.”

As Young and Cumberworth observe, Regnerus’s study soon became “one of the most hotly contested studies in twenty-first-century sociology.” This is putting it mildly. The almost immediate response was a firestorm of ideological denunciation, personal vituperation, and political pressure. The findings were widely and vehemently denounced. Hundreds of scholars and activists—the distinction was often unclear—demanded retraction of the study and investigation of Regnerus for misconduct. When the journal editor and university administrators, finding no basis for either action, refused, both were subject to intimidating legal action that went nowhere.

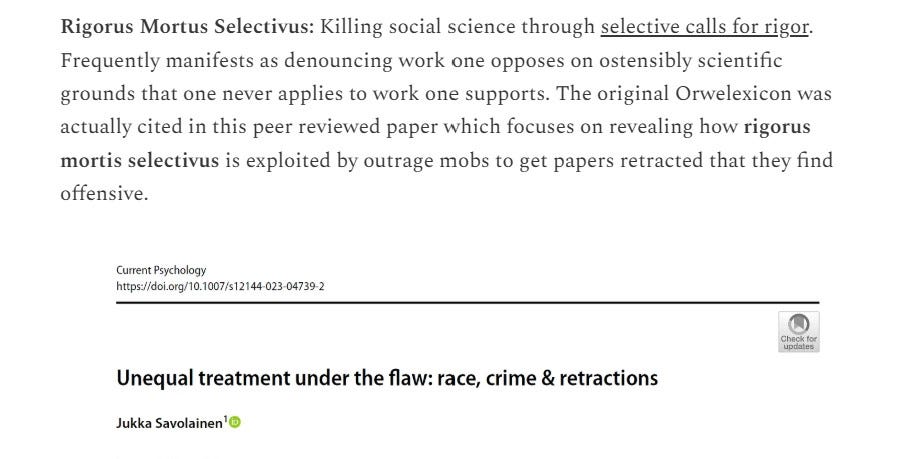

Lee here. The Regnerus Event was emblematic of the erosion of serious scientific norms around social science research and publishing. One of his most vehement critics called the paper “bullshit”; and this critic, who was on the editorial board of the journal that published it (Social Science Research), was then enlisted by the journal to do an “audit” of the journal’s practices, because people were calling for the editor’s head and investigations into Regnerus (who was investigated and cleared). That auditor described the publication of the Regnerus paper as a “failure of peer review.” A critique appearing in a different peer reviewed journal described the publication of the Regnerus paper as a “scandal.” Regnerus and the editor were widely denouned as having an “anti-gay agenda” and some of the criticisms, even at the time obviously political, were all decked out in the garb of scientific rigor and seriousness, as you will soon see in Sullins’ essay. From The Orwelexicon:

Regnerus survived and even made it to Full Professor, and the paper was never retracted, but this event foreshadowed even worse things to come over the next 12 years. Back to Sullins…

Regnerus responded to his critics in the best tradition of science: he publicly posted his entire dataset, inviting them to analyze it for themselves and to try to overturn his findings. Eventually, two main lines of scholarly critique emerged to suggest that his analysis had exaggerated differences due to same-sex parenting: first, that Regnerus had misclassified some persons as “raised by same-sex parents” who did not belong in that category, and second, that he had conflated family structure with transitions between families, which are known to be harmful to child development. Young and Cumberworth revisit both issues with new analyses.

In 2015, sociologists Simon Cheng and Brian Powell published a critique questioning some of Regnerus’s classification decisions. After close examination of the data, they determined that 103 (44 percent) of the 236 cases that Regnerus had classified as “raised by parents that had a same-sex relationship’’ had been misclassified. Fifty-three persons in that crucial category, for example, had reported living with one of the same-sex partners for less than a year, and another fifteen for only two to four years. This meant that these children had spent most of their childhood in the care of other, almost always heterosexual, parents, presenting a fundamental challenge to Regnerus’s claim that these children’s disadvantages were due to having been raised by same-sex parents.

Other cases simply had inconsistent or unreliable information. Regnerus had also dropped 116 cases from the “intact biological family” category because they had divorced or separated after the child had grown and launched from the family. Both of these questionable classification choices by Regnerus increased the apparent differences between same sex-parented children and those with their own biological parents. Were the differences he found simply artifactual, the result of these and other debatable analytic decisions? Cheng and Powell showed that, when these questionable classifications were reasonably corrected, all of the important differences reported by Regnerus became statistically insignificant, effectively too uncertain to know if they actually existed.

In 2015, Stanford sociologist Michael Rosenfeld addressed the issue of family transitions. As already noted, the experience of family disruption, which forces a child to transition to a new set of parent figures and family members, is well known to impede a child’s development. Same-sex partners, moreover, often begin their relationship following the divorce or dissolution of a former heterosexual relationship. “Estimates of the effect of same-sex couples on children’s outcomes are nearly always confounded by the impact of the prior heterosexual relationship and its breakup,” argued Rosenfeld. Regnerus had failed to adjust his findings for such transitions, even though his main reference category of “intact biological family” had, by definition, excluded any transition in family arrangements while same-sex partners often underwent multiple transitions. The effects Regnerus observed when he compared the two groups, Rosenfeld contended, may not have been due to a difference between biological parents and same-sex parents, but to a difference between families where children experienced no family disruptions and those where they may have experienced many. Using the same NFSS data, Rosenfeld showed that adjusting for childhood family transitions reduced the statistically significant negative outcomes associated with gay fathers from the eleven Regnerus had reported to only five and with lesbian mothers from Regnerus’ twenty-five to just two, neither necessarily negative. Rosenfeld concluded that “Regnerus’s (2012a) analysis was flawed by his failure to control for childhood family instability,” and thus in reality “same-sex couple parents . . . are weakly or not at all associated with negative adult outcomes.”

Regnerus responded to both critiques with revised analyses and/or a defense of his methodological choices. Reclassifying variables changed, but did not eliminate, negative outcomes with same-sex parents, he argued, and high instability was not an alternative explanation for poorer child outcomes but was baked into same-sex partnerships. And there the matter stood, essentially a standoff between rival theoretical perspectives, though with almost all social scientists in agreement with Regnerus’s critics, until Young and Cumberworth revisited the debate and the data.

Young and Cumberworth note that both Rosenfeld and Cheng and Powell stacked the deck against finding statistical significance by analytical choices that reduced the sample size. Referring to Cheng and Powell’s critique, they comment: “It is not a fair assessment of the data to report that significance levels fall after dropping as much as 44 percent of the treatment group [103 cases]: Of course statistical significance will be lower when the sample is smaller.” Rosenfeld is an even greater offender: he “drops all respondents who are missing on any of the nineteen outcome variables he used (17.5 percent [of the entire dataset, or 523 cases])”. Rosenfeld’s final statistical model discarded (needlessly, in their view) 1,282 cases, which was 43 percent of the entire dataset.

The more important problem of the critics, however, was their assumption that eliminating the statistical significance of an LGBT effect proved that it did not exist. “A key mistake that both critics make,” Young and Cumberworth assert, “is to focus exclusively on significance testing, particularly as they drop substantial portions of the data.” Unlike Regnerus, “[n]either Rosenfeld nor Cheng and Powell ever report a substantive estimate or regression coefficient for their [re-analyzed] LGBT effects [showing how large or small the difference was] but instead report only the significance tests.”

This critique is not new. In 2015, University of Kansas family scholar Walter Schumm observed:

Recently, Cheng and Powell (2015) reanalyzed data from the New Family Structures Study and reported that they only found four significant results, compared to the twenty or more reported by Regnerus (2012). However, they did not report effect sizes for any of their results. Because they reduced the number of same-sex parent families considerably, it is actually possible that the effect sizes were unchanged, but due to the smaller sample statistical significance was lost. Had they shown that the effect sizes were also reduced, that would have implied far more strongly that the previous NFSS results were a result of poor measurement and methodology.

Young and Cumberworth do not seem to be aware of this earlier critique that confirms their own.

As Young and Cumberworth explain when introducing their multiverse method: “A [statistical] significance test can be seen only as an initial starting point; . . . statistical findings should be evaluated as much by their robustness [strength and persistence] as their ‘significance.’” They formalize the evaluation of robustness in an “influence analysis” that considers how much alternative specifications change the overall results of a model. For the Regnerus findings, the influence analysis shows that each critique results in models that reduce the strength by about half, but they never eliminate the negative effect of having had lesbian or gay parents.

Rosenfeld’s critique stumbles badly on another point. He presents accounting for outcome differences as a choice between family structure (biological or gay parents) and family transitions, but as Young and Cumberworth note, “these approaches could be combined” into a both/and analysis that includes both effects. When they do just this, they find that the combined effect of transitions and LGBT parent “reduces the effect of transitions and increases the effect of LGBT parent.” In other words, Rosenfeld’s contention that family transitions would render the LGBT parent effect spurious is mistaken, as a matter of evidence. Both transitions and having an LGBT parent, it turns out, contribute to negative outcomes for children.

Young and Cumberworth admit that “we were surprised by the robustness of the Regnerus finding.” Although the critical analyses resulted in reduced estimates of the LGBT parent effect, “[o]ur surprise was discovering that in these data a negative effect [of an LGBT parent] is nonetheless still robust and that there are essentially no opposite-signed results [showing any benefit from having an LGBT parent].” Future debate is possible, they observe, “over the magnitude of the LBGT parent effect or over the quality of the data but not over the existence of an LGBT parent effect in this dataset.” To the extent that the NFSS presents an accurate picture of parenting family structures—and they have their doubts—it presents valid evidence of negative child outcomes that follow from having been exposed, even for a short time, to the involvement of gay or lesbian parents.

To interpret this result, Young and Cumberworth reflect that “[s]ocial theory seeks to predict and explain phenomena, not data per se.” They present this as a call for better data, which is well justified, but it also appeals to a deeper truth. Data models can present more or less accurate pictures of the real social world, but what is important is not the pictures but the reality itself. Phenomena that are real—what classic sociological theorists called “social facts”—tend to be stubbornly resistant to efforts to ignore or deny them. It is possible, as Young and Cumberworth suggest, that more accurate measures of family structure could rebut the existence of an LGBT parent effect. Another possibility, however, is that the advantage of stable biological parents for children, which they had expected to be a fragile finding in the first place, persisted so robustly in the data despite the critiques, not because the arguments to defend this finding are cleverer than the arguments to dislodge it (although both are pretty clever), but because it reflects a stubborn social fact rooted in human reality itself.

Young and Cumberworth hope that their strong validation of Regnerus’s controversial conclusions might lead to renewed debate over the study and same-sex parenting. To that end they have, like Regnerus, made the raw data underlying their findings public and thus they invite a response. They do not present their conclusions as the final word and express a refreshing openness to having their critique itself critiqued.

Suppressing disfavored ideas from consideration has serious consequences for the possibility of scientifically informed public discourse in our day.

Commenting Guidelines

Before commenting, please review my commenting guidelines. They will prevent your comments from being deleted. Here are the core ideas:

Don’t attack or insult the author or other commenters.

Stay relevant to the post.

Keep it short.

Do not dominate a comment thread.

Do not mindread, its a loser’s game.

Don’t tell me how to run Unsafe Science or what to post. (Guest essays are welcome and inquiries about doing one should be submitted by email).

To Unsafe Science,

As someone who has been involved in these debates for years, and as the Founder of the Ruth Institute, I very much appreciate you reposting this article, as well as your commentary. Thank you.

The Regnerus “New Family Structures Study” is often cited in these debates, but it didn’t actually study children raised from birth by stable same-sex couples. Most respondents counted as having “gay parents” had only ever reported that a parent once had a same-sex relationship—often after divorce or disruption—so what the NFSS mostly captures is family instability, which is already known to hurt outcomes for kids regardless of parent orientation.

The recent “multiverse” re-analysis confirms that Regnerus’s negative effect is robust within that flawed dataset, but the authors themselves stress that the data are limited and misclassified (Young & Cumberworth, The Multiverse of Methods, 2024). Saying the effect persists in NFSS is not the same as proving that same-sex parenting is harmful—it just means the dataset can’t separate the impact of instability from parent orientation.

By contrast, modern high-quality studies that actually follow children raised from birth by same-sex parents find no disadvantages, and sometimes small advantages. For example: Dutch population-register research (Demography, 2021; American Sociological Review, 2020) shows kids of same-sex parents doing as well or better academically, and the U.S. National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study found no mental health disadvantages at age 25 (New England Journal of Medicine, 2020). Families like mine, where children were born via surrogacy and raised from birth by two dads, were never in the NFSS at all. The best evidence we have on those families shows kids doing just as well as their peers