Ceteris Paribus: Red States, Blue States, Longevity, and Health

Settling a dispute between Dr. Duarte and Dr. Knowles on red state/blue state policies and their impact lifespans. By Nathanial Bork

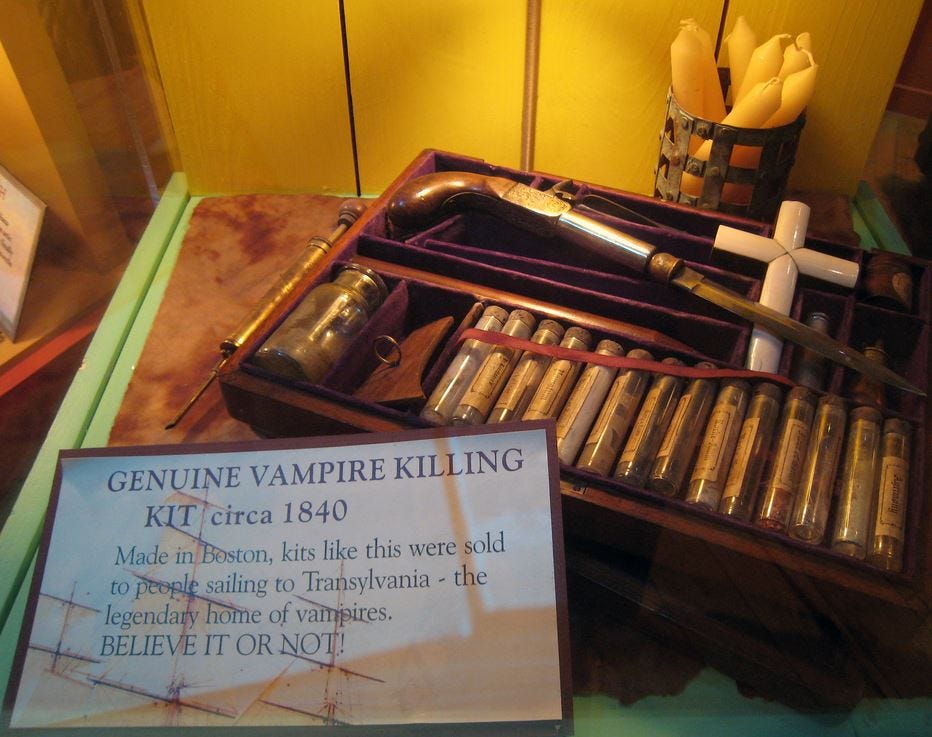

This is a repost of an essay that appeared on Nate Bork’s Substack, What the Other Side is Saying, which I already recommend because he does a great job of steelmanning opposing sides in various controversies. This, however, is his own wooden stake style essay Wooden stakes kill vampires and wooden stake essays kill the bad science that sucks the blood from serious and rigorous social science.

Nathanial Bork is working on his second Ph.D. in Education Reform as Distinguished Fellow at the University of Arkansas. His first doctorate was in Political Science from Colorado State where he specialized in Political Theory. His upcoming book Climate of Mistrust: How Higher Education Polarization Leads to Skepticism about Climate Change (and Everything Else) explores the social pathologies plaguing our universities and what can be done to heal them, and is due out later this year. He spends his summers and holidays in Colorado with his daughter and his free time going on motorcycle adventures throughout the Ozarks.

By Nathanial Bork

[Note - Dr. Knowles originally agreed to review this before I published it, and as of 3-8-25 my last couple of attempts to reach out to him were unsuccessful. So the new plan is to publish now and edit this if/when he gets back to me.]

Dr. Duarte is a Twitter friend of mine and a fellow academic pirate, and he recently made some pretty strong claims1 about a paper published in Nature Medicine written by Jay Van Bavel, Shana Kushner Gadarian, Eric Knowles & Kai Ruggeri titled ‘Political Polarization and Health.’ Their article claimed that blue state’s liberal policies explained higher life expectancies.

While Dr. Duarte and I were discussing it on X, Dr. Knowles joined the conversation and said that Dr. Duarte was wrong about the studies they had used to reach their conclusion. I promised them both that I’d do my homework instead of just trusting a member of my academic ingroup, and here’s how my investigation went.

Summary

Van Bavel et al. (2024) asserted in Nature Medicine that political polarization, via state policy differences, shapes U.S. life expectancy, with liberal states outperforming conservative ones. Their claim that people in states with more liberal social policies live longer cites Montez (2020) and highlights COVID-19 disparities (Wallace et al., 2023). Duarte challenged this as methodologically flawed and ideologically skewed (Duarte, 2025), while co-author Dr. Eric Knowles defends its grounding in Montez et al. (2020). The core issue is Ceteris Paribus (all other things being equal), and whether Van Bavel et al. (2024) chose the correct variables to compare populations.

I reviewed their arguments and have added a list of possible exogenous factors that should be considered in future research.

The Dispute

Van Bavel et al. (2024) link polarization to health, citing a 43% higher excess death rate among Republicans during COVID-19 (Wallace et al., 2023) and Montez (2020)’s New York-Mississippi comparison (80.6 vs. 74.4 years). Duarte (2025) deemed Montez (2020) a non-empirical essay, unfit for causal inference, and critiques its omission of race. Mississippi’s population is 38% Black population while New York’s is 15% (Andrasfay & Goldman, 2022). The paper they cite also has a liberal bias. Knowles (2024) countered that Montez (2020) synthesized Montez et al. (2020), which models a 2.8-year life expectancy gain for women under liberal policies, bolstered by COVID-19 evidence (Gollwitzer et al., 2020).

Duarte’s Critique

Duarte’s assessment of Montez (2020) as analytically weak is generally accurate, if not a bit blunt, as its descriptive table lacks statistical rigor (Montez, 2020), falling short of causal standards (Ioannidis, 2005). Race omission is a critical flaw as there is a significant Black-White life gap in life expectancy (73.2 vs. 77.3 in 2021, Andrasfay & Goldman, 2022). This racial gap suggests demographic composition drives disparities, which was not addressed by Montez et al. (2020)’s immigration-only controls (Borrell et al., 2006).

Duarte’s charge of bias that Van Bavel et al. (2024) favor liberal policies is reasonable as it doesn’t include counterexamples like school closure harms (Betthäuser et al., 2023), and thus fails to have a balanced approach (Tetlock, 1994).

However, his dismissal of Montez et al. (2020) as “invalid” overreaches, given its 50-state scope, but highlights causal overstatement (Hill, 1965).

Knowles’ Defense

Knowles (2024) defends Montez et al. (2020)’s 45-year, 135-policy analysis, estimating gun control adds 0.5 years for women, supported by firearm mortality reductions for both sexes (Fleegler et al., 2013). COVID-19 data—14% less distancing in red counties (Gollwitzer et al., 2020) reinforces polarization’s toll.

Yet, Montez et al. (2020) admits associative limits, and Van Bavel et al.’s (2024) “impact” phrasing exceeds this (Hill, 1965). Knowles’ silence on race weakens his rebuttal, despite the paper’s breadth (Harper et al., 2007).

Conclusion

Duarte’s critique of methodological gaps regarding race and rigor is correct, upheld by Montez (2020)’s thin evidence and Montez et al. (2020)’s confounder oversight. Knowles’ data scope is robust, but causal claims falter without addressing Duarte’s points fully.

Better Models for Partisan Longevity Research

Beyond policy, exogenous factors may drive disparities:

1. Socioeconomic Inequality: Red states’ higher poverty (e.g., Mississippi 19.6% vs. New York 13.9%) links to worse health (Pickett & Wilkinson, 2015), compounded by economic shocks (Case & Deaton, 2020).

2. Cultural Norms: Red-state individualism resists health measures (Gollwitzer et al., 2020), with tobacco norms entrenched historically (Brandt, 2007).

3. Environmental Hazards: Red states’ industrial bases (e.g., coal in West Virginia) increase exposure risks, beyond policy control (Montez et al., 2020).

4. Healthcare Access: Rural red states face provider shortages (e.g., Mississippi 12.3 vs. New York 22.1 docs/100,000), a market-driven gap (Rural Health Information Hub, 2022).

5. Demographic Shifts: Red states’ older, minority-heavy populations (e.g., Mississippi 38% Black) and blue-state migration of young professionals skew outcomes (Andrasfay & Goldman, 2022).

Exogenous factors such as poverty, culture, environment, access, and demographics offer a fuller lens on red-blue health and longevity gaps. Adding them, and including race, would vastly improve Van Bavel et al. (2024)'s work and create the necessary conditions for ceteris paribus and produce robust enough models (Diez Roux, 2001) to compare the populations of red and blue states.

References

Andrasfay, T., & Goldman, N. (2022). Reductions in US life expectancy during the COVID-19 pandemic by race and ethnicity: Is 2021 a repetition of 2020? PLOS ONE, 17(8), e0272973. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272973

Betthäuser, B. A., Bach-Mortensen, A. M., & Engzell, P. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence on learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(3), 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01506-4

Borrell, L. N., Kiefe, C. I., Williams, D. R., Diez-Roux, A. V., & Gordon-Larsen, P. (2006). Self-reported health, perceived racial discrimination, and skin color in African Americans in the CARDIA study. Social Science & Medicine, 63(6), 1415–1427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.008

Brandt, A. M. (2007). The cigarette century: The rise, fall, and deadly persistence of the product that defined America. Basic Books.

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2020). Deaths of despair and the future of capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Diez Roux, A. V. (2001). Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. American Journal of Public Health, 91(11), 1783–1789. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1783

Duarte, J. (2025, February 14). NYU social psychologists make false claims about gun control and life expectancy. Valid Science by José Duarte, PhD. Substack.

Fleegler, E. W., Lee, L. K., Monuteaux, M. C., Hemenway, D., & Mannix, R. (2013). Firearm legislation and firearm-related fatalities in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(9), 732–740. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1286

Gollwitzer, A., Martel, C., Brady, W. J., Pärnamets, P., Freedman, I., Knowles, E. D., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2020). Partisan differences in physical distancing are linked to health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(11), 1186–1197. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-00977-7

Harper, S., Lynch, J., Burris, S., & Davey Smith, G. (2007). Trends in the black-white life expectancy gap in the United States, 1983-2003. JAMA, 297(11), 1224–1232. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.11.1224

Hill, A. B. (1965). The environment and disease: Association or causation? Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 58(5), 295–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/003591576505800503

Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2005). Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Medicine, 2(8), e124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124

Knowles, E. (2024, October 28). [X thread starting with post ID 1888434805974475190]. https://x.com/eric_knowles/status/1888434805974475190

Jennifer Karas Montez, How State Preemption Laws Prevent Cities from Taking Steps To Improve Health and Life Expectancy, Scholars (Mar. 6, 2018). Link to PDF can be found here. (mentioned in the Twitter exchange)

Montez, J. K. (2020). Policy polarization and death in the United States. Temple law review, 92(4), 889. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8442849/

Montez, J. K., Beckfield, J., Cooney, J. K., Grumbach, J. M., Hayward, M. D., Koytak, H. Z., Woolf, S. H., & Zajacova, A. (2020). US state policies, politics, and life expectancy. The Milbank Quarterly, 98(3), 668–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12469

Pickett, K. E., & Wilkinson, R. G. (2015). Income inequality and health: A causal review. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 316–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.031

Rural Health Information Hub. (2022). Healthcare access in rural communities. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/healthcare-access

Tetlock, P. E. (1994). Political psychology or politicized psychology: Is the road to scientific hell paved with good moral intentions? Political Psychology, 15(3), 509–529. https://doi.org/10.2307/3791569

Van Bavel, J. J., Gadarian, S. K., Knowles, E., & Ruggeri, K. (2024). Political polarization and health. Nature Medicine, 30(11), 3085–3093. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03307-w

Wallace, J., Goldsmith-Pinkham, P., & Schwartz, J. L. (2023). Excess death rates for Republican and Democratic registered voters in Florida and Ohio during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Internal Medicine, 183(9), 916–923. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.1154

Lee here. Nate’s post links to Duarte’s Substack post on the Van Bavel et al article that is the centerpiece of Nate’s essay. You can find Duarte’s X post here. Full disclosure: Eric Knowles blocked me years ago because, when I pointed out that what they call “system justification” and only apply to the types of oppression and exploitation that progressive care about, one could just as easily view “low system justification” as “justifying confiscatory govt. policies,” and tweeted a picture of Stalin along with it. Eric took offense and blocked me (which is his right of course; for the X uninitiates, this means I can no longer respond directly to his tweets). But those who dress up their propaganda as scholarship hate being exposed, but especially via the “shoe on the other foot test” as here.

However, I cannot resist pointing this out. This is from the original conversation between Duarte and Eric Knowles on X:

I looked at this. The word “gun” appears once in their paper, and in a sentence with no references whatsoever. The paper is online here. Shown is the beginning of the paper, and my search for the word “gun” in it:

Gun appears one time in the entire paper. Note that it has no citations:

Let’s return to the exchange on X.

They did not cover this. Update. Joe Duarte, in the comments, pointed out that they did cite Montez (2020) referring to “firearms,” rather than guns. Here is the van Bavel et al quote:

People who live in states with more liberal social policies, such as generous Medicaid coverage, higher taxes on cigarettes, more economic support (for example, minimum wages) and more firearm regulations live longer41 than their counterparts in states that embrace more conservative policies.

41 is the citation to Montez (2020). However, Montez (2020) compared just one liberal (NY) to one conservative (Mississippi) state. Thus, the statement “People who live in states…” is not justified by Montez (2020). Worse, Montez’s Table 1 (screenshotted at the end of this footnore) clearly reports the data for all 50 states in summary form, raising (over and above the confounder issues raised in Nate Bork’s essay) the questions:

Was this particular comparison cherrypicked to make a point?

Why didn’t Montez simply correlate number of gun laws with life expectancy for the whole country?

Why did van Bavel et al make such a big deal of what is essentially an anecdote?

This sort of thing — a strong yet weakly evidenced claim — is one of the hallmark’s of propaganda masquerading as social science. Social scientists should not be in the business of making shit up, either in peer review or on social media.

Nice that you posted this.

Nate is too generous toward Montez, et al. (not to be confused with the solo Montez essay that Van Bavel and Knowles cited).

It's invalid and that it covers 50 states is irrelevant. Covering 50 states doesn't make something valid. It's invalid for the reasons I go into in my report. We don't know what their gun control variable is, because they don't tell us, it has things like "brady law" when that's a federal law in force since the late 90s, "assault weapon" ban when that was a federal law for a good chunk of their period, etc.

We don't know what most of their nine laws refer to, what the rubric was, what the state ratings were, or what it means to subtract zero from one, which is what they say they did.

There are more reasons it's invalid, like that they didn't control for race.

And as a reminder, they didn't actually find a general effect – Knowles lied about that. (This was the source he scrambled for as a fallback – they never cited it in their paper.) Their only effect was for women, which makes even less sense.

In fact, an effect for men, women, or general pop is mathematically impossible if we assume these arbitrarily chosen gun control laws affected life expectancy by reducing murder and/or suicide rates (it would have to be bottom line rates, not just via gun). Those would be the obvious implied pathways, but they never actually articulate a theory – not Montez, not Knowles. Gun laws won't reduce cancer or something, so it's got to be murder/suicide. But it turns out that even a chunky reduction of those wouldn't reduce life expectancy by anywhere near the 0.5 years they claim for women. (And women are much less likely to be killed with a gun anyway.)

There aren't nearly enough murders and suicides to drive such an effect, so no dice. The action is elsewhere. This is outlined in my report, with the life table example.

You guys all pretty much do that thing where you treat a published study as being valid by default, wanting to be nice to the authors, collegial, etc. No, just because something is published doesn't mean it carries any inherent validity or epistemic standing. The Montez, et al. study is nothing, has no standing. We can't do anything with it. If we don't know what someone did, if we can't see what they did, their ratings, data, etc. and they made big errors from what we can see, that's not anything. It shouldn't have been published and it's just polluting the literature and our brains.

As far as your search for "gun" in their paper, try "firearm(s)". It won't help them much, but that's where their false claim is, where they cite the Montez essay.

It is kind of shocking they neglected to include demographics. I would think that would be the prime driver, not just race but age and such. I'd have thought that per capita income, race categories and some age distribution ranges would be obvious first choice controls one would include, but maybe that's just an economist thing.